HOME OXFORD SONGS NOTES BIOGRAPHIES SCORES CREDITS / ACKNOWLEDGMENTS BONUS TRACK ALSO ON NAVONA RECORDS ABOUT NAVONA RECORDS

Ralph Vaughan Williams(1) set it twice, or perhaps three times (depending upon how you count a barely altered arrangement of one of the versions). Our recording sports the more elegant of Ralph Vaughan Williams’ settings. I set “Orpheus with his lute made trees,” once; as the first movement of my Sonata for Violin and Voice. The motivation for this piece is the Orpheus figure: the poet, composer, performer; all bound in one character. It is even possible, hypothetically, to perform the Sonata for Violin and Voice as a solo work; the violinist singing the vocal line while playing. Realistically, the piece is too contrapuntally complex for the two performers to become one, except were the actual Orpheus available. The Sonata for Violin and Voice is about itself, about the musicians, and about the composer. “Orpheus with his lute made trees and the mountain tops that freeze bow themselves when he did sing.” Shakespeare is – I believe – relating to us that as Orpheus constructed his lute from trees; the trees that (Ovid tells us) supplicated themselves to the music he made, are responding empathetically to Orpheus because they are a reflection of his own creation. The tree that falls in this forest is heard, because man (Orpheus) has declared the tree real through art. The second movement of my Sonata for Violin and Voice follows the first without pause, and shifts from paean to plaint. Shakespeare’s Sonnet CIII laments the poet’s loss of inspiration. “Alack,” he begins with histrionic mendacity, “what poverty my muse brings forth.” The poem is a clever lie, in which the bard bemoans his inability to adequately praise the object of his affection, in the form of a perfectly constructed encomium to his beloved. “Blame me not, if I no more can write,” he writes. Why can he not write? “Look in your glass, and there appears a face that overgoes my blunt invention quite.” It’s a line that belies itself. The conceit of the mirror in the sonnet, I mirror in my setting, through the use of melodic reflections, the kind of techniques I learned from my study of the serial music of Arnold Schönberg, whose muse brought forth such poverty that he wrote no music for more than a decade while pondering what new direction he should take, eventually establishing dodecaphony in 1923, (having stolen the basic concept from the talentless Austrian composer Josef Matthias Hauer). Schönberg’s school of serialism has fallen into desuetude, but the techniques he utilized I ape; techniques I learned from Schönberg’s amanuensis, Richard Hoffmann. Before attending Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, and studying with Hoffmann, I first learned the basics of the craft of composition from Karel Husa, (whose Music for Prague is one of the greatest works ever written for band) when I was fifteen years old. In 1971, studying with the Czech composer in North Carolina, I wrote a duet, that I would revisit nearly thirty years later, and with a few slight tweaks, adapt to the text from Sonnet CXXVIII. This became the third movement of my Sonata for Violin and Voice. In Sonnet CXXVIII, Shakespeare tells us that “my music play'st Upon that blessed wood whose motion sounds,” but he deliberately writes not merely “my music play’st,” but instead: “How oft when thou, my music, music play'st.” The first “music” is the human object of his affection, personified as the music itself (the second).

I won’t be criticized for adapting earlier works, tweaking them a bit, and utilizing them in new venues. It is a common practice of the trade of composer. Czech born composer Erich Wolfgang Korngold emigrated to Hollywood in 1934, to adapt Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream for a movie. In 1938 he returned to Hollywood from his home in Austria, just avoiding being caught in the Holocaust. Here in the United States he became our country’s foremost creator of movie scores, oft imitated but never equaled. He was the first composer to receive an Oscar for a film score in 1938. Previous Oscars for movie music had been awarded to the executives of the film company’s music department. He was as well a composer of prodigious talent and varied interest; penning operas, songs, and orchestral music. He repeatedly revisited Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, creating incidental music for orchestra and reissuing it in several formats; including a suite for piano, a suite for violin and piano, and even a version for string quartet which was lost for decades, but recently found (but only performed – as of this writing – once and never professionally recorded. The Shakespeare Concerts plans to remedy this lacunae presently). The version of Much Ado About Nothing for violin and piano was necessitated when performances of the play at the Schönbrunn Palace (in Vienna) were so popular they extended past the orchestra’s contract. Korngold quickly penned the violin and piano version and played the rest of the performances himself. Though his native tongue was not English, being born in a Jewish home in Brno, at the time a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (now a part of the Czech republic) he was fascinated by Shakespeare; much as Shakespeare, whose native tongue wasn’t Latin, was fascinated by Publius Ovidius Naso, who we know from the abbreviated version of his name: Ovid.

Branislava Nijinska in Hollywood's 1934 Midsummer Night's DreamOur familiarity with the myth of Orpheus – those of us with English as our native tongue – descends from the translation of Ovid’s The Metamorphoses by the straitlaced Arthur Golding while he was acting as tutor to his nephew, Edward DeVere, the 17th earl of Oxford. The earl would grow up to become the world’s greatest playwright, known by his pseudonym: William Shakespeare. It is difficult to comprehend why Arthur Golding – a strict Calvinist, the translator of Calvin’s commentaries and sermons into English – would choose to bring to an English speaking audience Ovid’s tales of lust, rape, and pagan religion. I can’t believe that this was a result of anything other than young William Shakespeare’s presence at his side during the entirety of time the translation was being created. It is no coincidence that Shakespeare’s most frequently utilized book, outside of the bible, is Golding’s translation of The Metamorphoses. My fellow Oxfordian, Hank Whittemore(2) sums it up, claiming Golding “was ‘apparently’ translating the Ovid because it’s far more likely that it was done by the young earl himself. Golding was a puritanical sort who translated Calvin’s Psalms of David (which he dedicated to Oxford, his nephew) and would not have been crazy about translating Ovid’s tales of passion and seduction and lovemaking as well as incest by pagan gods and goddesses. No, he was in every way incapable of it.” I might not be willing to take Hank’s final step and assert that the English language translation of The Metamorphosis was a teenage DeVere’s work, but I can absolutely see him as participating in its creation with Golding. No one, orthodox or Oxfordian, denies the primacy of Golding’s The Metamorphoses in the Shakespeare oeuvre. That The Metamorphoses took shape in the presence of the 17th earl (and finished by the 17th earl’s 17th birthday) is unsurprising. Insignificantly, my initial composition of the third movement of the Sonata for Violin and Voice preceded my 16th birthday. Shakespeare was a great deal smarter than me, and if I could craft some acceptable counterpoint before I reached maturity, Shakespeare wouldn’t have had a problem with the intellectual exercise of grappling with a little Latin and Publius Ovidius Naso. The harder task for the young earl might have been holding Golding in his seat, convincing him that the Ovid was art, not perversion. Would Golding not have considered his working on this art hypocritical, the lewd myths an acerbic commentary on the puritanical society he longed to establish throughout England? How would his making the Greek myths available to English speakers serve the reformed faith?

Branislava Nijinska in Hollywood's 1934 Midsummer Night's DreamOur familiarity with the myth of Orpheus – those of us with English as our native tongue – descends from the translation of Ovid’s The Metamorphoses by the straitlaced Arthur Golding while he was acting as tutor to his nephew, Edward DeVere, the 17th earl of Oxford. The earl would grow up to become the world’s greatest playwright, known by his pseudonym: William Shakespeare. It is difficult to comprehend why Arthur Golding – a strict Calvinist, the translator of Calvin’s commentaries and sermons into English – would choose to bring to an English speaking audience Ovid’s tales of lust, rape, and pagan religion. I can’t believe that this was a result of anything other than young William Shakespeare’s presence at his side during the entirety of time the translation was being created. It is no coincidence that Shakespeare’s most frequently utilized book, outside of the bible, is Golding’s translation of The Metamorphoses. My fellow Oxfordian, Hank Whittemore(2) sums it up, claiming Golding “was ‘apparently’ translating the Ovid because it’s far more likely that it was done by the young earl himself. Golding was a puritanical sort who translated Calvin’s Psalms of David (which he dedicated to Oxford, his nephew) and would not have been crazy about translating Ovid’s tales of passion and seduction and lovemaking as well as incest by pagan gods and goddesses. No, he was in every way incapable of it.” I might not be willing to take Hank’s final step and assert that the English language translation of The Metamorphosis was a teenage DeVere’s work, but I can absolutely see him as participating in its creation with Golding. No one, orthodox or Oxfordian, denies the primacy of Golding’s The Metamorphoses in the Shakespeare oeuvre. That The Metamorphoses took shape in the presence of the 17th earl (and finished by the 17th earl’s 17th birthday) is unsurprising. Insignificantly, my initial composition of the third movement of the Sonata for Violin and Voice preceded my 16th birthday. Shakespeare was a great deal smarter than me, and if I could craft some acceptable counterpoint before I reached maturity, Shakespeare wouldn’t have had a problem with the intellectual exercise of grappling with a little Latin and Publius Ovidius Naso. The harder task for the young earl might have been holding Golding in his seat, convincing him that the Ovid was art, not perversion. Would Golding not have considered his working on this art hypocritical, the lewd myths an acerbic commentary on the puritanical society he longed to establish throughout England? How would his making the Greek myths available to English speakers serve the reformed faith?

Fifteen years after composing Mythes in 1915, the composer Karol Maciej Szymanowski congratulated himself and his violinist, Paweł Kochański, as being responsible for the advances in violin writing by all subsequent composers, especially Prokofiev and Stravinsky. Touting his own brilliance in a letter to the dedicatee of Mythes, Zofia Kochańska (Paweł Kochański’s wife), the composer proclaimed: “In Mythes . . . Pawełek and myself have created a new style, new expression of violin playing, a truly epoch-making thing. All (similar) works by other composers - be they most brilliant ones - were written later, that is under direct influence of 'Mythes.'” We don’t know what Zofia’s reaction was to this boast, but there is truth in Szymanowski’s braggadocio. (I admit, myself, I studied his score assiduously before penning the first movement of my Sonata for Violin and Voice). Szymanowski’s work is a great leap forward in solo violin writing, a new approach to the instrument in which previously underutilized aspects of the instrument’s capabilities are explored. The myths of Mythes are familiar to readers of Ovid. The first movement, “La fontaine d’Arethusa,” describes the nymph, Arethusa, pursued by the river god Alpheus (all rivers having their own god), pleading with Artemis to protect her virginity from Alpheus, who is bent on rape. Artemis transforms her acolyte Arethusa into a cloud, but this fails to deter Alpheus as the nymph begins to sweat profusely, revealing her presence. Artemis changes her again, into a fountain. Alpheus would eventually ooze his way into the fountain, and so Artemis’ attempt to protect her follower ultimately would fail.

The Fountain of Arethusa in Siracusa Mythes’ second movement, “Narcise,” is the story of Narcissus and Echo. Echo, an oread, aids Zeus in concealing from his wife, Hera, the adulterous god’s affairs. She detains the Queen of the Gods with inventive chatter while Zeus philanders. Discovering Echo’s complicity, Hera punishes the mountain nymph by making her incapable of ever again uttering a novel word. She can only repeat what she hears. Echo falls in love with Narcissus (son of a river god and nymph), but Narcissus has no interest in her; not because of her affliction, but rather because Narcissus is looking for someone more attractive. He finds his perfect love when he spies his reflection in a pool. Echo, dismissed, turns into an auditory reflection. Meanwhile, Narcissus can’t entice his own image – which he thinks is a water spirit – out of the pond. Refusing to move from his reflection, he dies and becomes a flower.

Mythes’ second movement, “Narcise,” is the story of Narcissus and Echo. Echo, an oread, aids Zeus in concealing from his wife, Hera, the adulterous god’s affairs. She detains the Queen of the Gods with inventive chatter while Zeus philanders. Discovering Echo’s complicity, Hera punishes the mountain nymph by making her incapable of ever again uttering a novel word. She can only repeat what she hears. Echo falls in love with Narcissus (son of a river god and nymph), but Narcissus has no interest in her; not because of her affliction, but rather because Narcissus is looking for someone more attractive. He finds his perfect love when he spies his reflection in a pool. Echo, dismissed, turns into an auditory reflection. Meanwhile, Narcissus can’t entice his own image – which he thinks is a water spirit – out of the pond. Refusing to move from his reflection, he dies and becomes a flower.

The Metamorphosis of Narcissus by Salvador DaliIn the final movement, “Dryades et Pan,” Szymanowski utilizes violin harmonics to imitate the sound of the panpipe, a kind of flute in which tubes of different lengths are played alternately (rather than the technique of changing the length of one tube through the use of carefully placed holes). The panpipe was created by the god Pan when (stop me if you’ve heard this before) in pursuit of Syrinx – a disciple of Artemis, renowned for her chastity – the nymph is transmogrified by a gaggle of river naiads into hollow reeds. Hyperventilating, Pan grabs a handful of what he thinks is Syrinx, but pulls out the reeds, breathes over them, and voila, music! The dryads of the title are wood nymphs, not river nymphs (naiads). Szymanowski’s music is meant to describe Pan cavorting with dryads while playing a pipe made out of Syrinx.

The Metamorphosis of Narcissus by Salvador DaliIn the final movement, “Dryades et Pan,” Szymanowski utilizes violin harmonics to imitate the sound of the panpipe, a kind of flute in which tubes of different lengths are played alternately (rather than the technique of changing the length of one tube through the use of carefully placed holes). The panpipe was created by the god Pan when (stop me if you’ve heard this before) in pursuit of Syrinx – a disciple of Artemis, renowned for her chastity – the nymph is transmogrified by a gaggle of river naiads into hollow reeds. Hyperventilating, Pan grabs a handful of what he thinks is Syrinx, but pulls out the reeds, breathes over them, and voila, music! The dryads of the title are wood nymphs, not river nymphs (naiads). Szymanowski’s music is meant to describe Pan cavorting with dryads while playing a pipe made out of Syrinx.

Pan seduces Olympus with the Syrinx, from Museo Archaeologico Nazionale di NapoliThe story of Pan and Syrinx is the first story in the second book of The Metamorphoses, Metamorphosen Libri, in Latin: the "Books of Transformations." Characters metamorphosize from their original status as gods or men into animals, vegetables, and minerals. Ovid’s tome begins with the creation of the world and the Deucalion flood. I can imagine the pious puritan Golding gritting his teeth as he wrote of Prometheus, “tempering straight with water of the spring,” his creation: man “replete with majesty . . . And thus the Earth which late had neither shape nor hue did take the noble shape of man and was transformed new.” After the world is transformed into its present shape by Prometheus’ invention, man, The Metamorphoses describes the sordid pursuit of Daphne. Phoebus Apollo – the god of music, poetry, medicine, light and knowledge – chases her, but she would remain chaste. She begs her father to save her from Apollo’s amorous pursuit and he obliges (though Apollo seems like an excellent son-in-law to me); transforming her into a tree. Dame Edith Sitwell composed several poems for the English composer William Walton to set for spoken narration above a chamber orchestra, but he chose to set “Daphne” as a song for soprano and piano.

Pan seduces Olympus with the Syrinx, from Museo Archaeologico Nazionale di NapoliThe story of Pan and Syrinx is the first story in the second book of The Metamorphoses, Metamorphosen Libri, in Latin: the "Books of Transformations." Characters metamorphosize from their original status as gods or men into animals, vegetables, and minerals. Ovid’s tome begins with the creation of the world and the Deucalion flood. I can imagine the pious puritan Golding gritting his teeth as he wrote of Prometheus, “tempering straight with water of the spring,” his creation: man “replete with majesty . . . And thus the Earth which late had neither shape nor hue did take the noble shape of man and was transformed new.” After the world is transformed into its present shape by Prometheus’ invention, man, The Metamorphoses describes the sordid pursuit of Daphne. Phoebus Apollo – the god of music, poetry, medicine, light and knowledge – chases her, but she would remain chaste. She begs her father to save her from Apollo’s amorous pursuit and he obliges (though Apollo seems like an excellent son-in-law to me); transforming her into a tree. Dame Edith Sitwell composed several poems for the English composer William Walton to set for spoken narration above a chamber orchestra, but he chose to set “Daphne” as a song for soprano and piano.

Bernini's classic sculpture of Daphne Pursued by ApolloIn book VI of The Metamorphoses, appears a curt mention of Leda, the mother of Helen of Troy, the subject of our world’s first great saga: The Illiad. Perhaps Ovid didn’t want to tread on Homer’s legacy, so Leda occupies but one line of a roster of women seduced or raped by Zeus. “Because of its vast historical vision and agonizing pantomime of passion and conflict, ‘Leda and the Swan’ can justifiably be considered the greatest poem of the twentieth century,” opined Camille Paglia of William Butler Yeats’ expansive sonnet.(3) Paglia explains how this ode to a vicious rape, the “shudder in her loins” which is Zeus’ pleasure and Leda’s fear gives “birth to the entire classical era. From Leda's egg will hatch Helen and Clytemnestra, the sister femmes fatales. Faithless Helen will trigger the ten-year Trojan War, inspiring Homer's Iliad and Odyssey. Clytemnestra will slaughter her husband, Agamemnon, commander in chief of the Greek forces, and be murdered in turn by their vengeful son, Orestes. Aeschylus's trilogy about these events, the Oresteia, was the first great work of Western drama.” I became attracted to Yeats’ compact poem when I was a teenager, later setting it for piano and soprano in a sudden blow when asked to write an exercise in modulation between the keys of a and b, as part of an entrance examination at a nearby university. I like to imagine what the professor who reviewed it thought when he saw the lines to “Leda and the Swan” scrawled beneath a soprano line in a harmony exercise.

Bernini's classic sculpture of Daphne Pursued by ApolloIn book VI of The Metamorphoses, appears a curt mention of Leda, the mother of Helen of Troy, the subject of our world’s first great saga: The Illiad. Perhaps Ovid didn’t want to tread on Homer’s legacy, so Leda occupies but one line of a roster of women seduced or raped by Zeus. “Because of its vast historical vision and agonizing pantomime of passion and conflict, ‘Leda and the Swan’ can justifiably be considered the greatest poem of the twentieth century,” opined Camille Paglia of William Butler Yeats’ expansive sonnet.(3) Paglia explains how this ode to a vicious rape, the “shudder in her loins” which is Zeus’ pleasure and Leda’s fear gives “birth to the entire classical era. From Leda's egg will hatch Helen and Clytemnestra, the sister femmes fatales. Faithless Helen will trigger the ten-year Trojan War, inspiring Homer's Iliad and Odyssey. Clytemnestra will slaughter her husband, Agamemnon, commander in chief of the Greek forces, and be murdered in turn by their vengeful son, Orestes. Aeschylus's trilogy about these events, the Oresteia, was the first great work of Western drama.” I became attracted to Yeats’ compact poem when I was a teenager, later setting it for piano and soprano in a sudden blow when asked to write an exercise in modulation between the keys of a and b, as part of an entrance examination at a nearby university. I like to imagine what the professor who reviewed it thought when he saw the lines to “Leda and the Swan” scrawled beneath a soprano line in a harmony exercise.

Da Vinci's Leda and the SwanTwo years after composing “Leda and the Swan,” I wrote a chamber opera about a tenor named Enzo Cesare, who would serve as my metaphor for Orpheus. Though preceded by the composition of my Euripidean tragedy Hippolytus; The Tenor’s Suite was to be my first produced opera, premiering in Philadelphia in 1981. I loved the staging, tenor Noel Espiritu Velasco charging around the stage cursing audience, fans, and composers; but a beautiful videotape was lost when the videographer – mortified at his stentorian coughing beside his camera combined with his failure to synch the sound mikes – decided to abscond with the only copy, in shame and regret. In order to complete this recording project, I thought one particular aria from that opera, in my piano transcription, would be appropriate.

Da Vinci's Leda and the SwanTwo years after composing “Leda and the Swan,” I wrote a chamber opera about a tenor named Enzo Cesare, who would serve as my metaphor for Orpheus. Though preceded by the composition of my Euripidean tragedy Hippolytus; The Tenor’s Suite was to be my first produced opera, premiering in Philadelphia in 1981. I loved the staging, tenor Noel Espiritu Velasco charging around the stage cursing audience, fans, and composers; but a beautiful videotape was lost when the videographer – mortified at his stentorian coughing beside his camera combined with his failure to synch the sound mikes – decided to abscond with the only copy, in shame and regret. In order to complete this recording project, I thought one particular aria from that opera, in my piano transcription, would be appropriate.

“Hi Mr. Summer,

“Would you give some tips about your compositional concept of ‘You may think of art?’ It will help me to prepare better before the rehearsal tomorrow, I think…

Thank you!

SangYoung”

Benjamin Franklin Wedekind and his wife Tilly on stage in 1913I had called SangYoung Kim to come to the rescue of this very recording project, that was on the brink of collapse due to an unfortunate, but temporary cough our tenor, Neal Ferreira had developed, which delayed our recording; causing the unforeseen loss of the original pianist, due to prior scheduling commitments.(4)

Benjamin Franklin Wedekind and his wife Tilly on stage in 1913I had called SangYoung Kim to come to the rescue of this very recording project, that was on the brink of collapse due to an unfortunate, but temporary cough our tenor, Neal Ferreira had developed, which delayed our recording; causing the unforeseen loss of the original pianist, due to prior scheduling commitments.(4)

SangYoung had to learn some of my very difficult piano writing in short order, even more difficult than I normally inflict upon the interpreter because I had written the score in 1979 when I was 23 years old and hadn’t touched it in decades. I know she didn’t expect the reply she received – which I will relate presently – but I was glad to discover that she enjoyed my prolixity. After a preambulatory note on three specific technical matters I won’t bore you with here, I wrote to her, “‘You may think of art’ is the central aria in my opera, The Tenor’s Suite. It is meant to capture the two facets of the duplicitous agreement between the artist and the audience. 1) As a performer, your task, in all that you perform, is to make the work invisible. It must sound as if the music just sprang from your fingers with no preparation. This is part of ‘aesthetic distance,’ the idea that the listener becomes so immersed in the music she doesn’t realize it took craft and planning to make it seem the way it does. . . 2) As a composer, my task is to write a piece that the listener thinks sprang unbidden, from my head, like Athena from Zeus. She should not apprehend that any work or preparation occurred during composition. It’s the myth of music springing fully realized into the composer’s brain. Ars est celare artem. The art is in concealing the art. True art conceals the means by which it is achieved.

“‘You May Think of Art’ is about two ‘lies.’ The second ‘lie’ is captured in the main theme, the B theme: ‘We Artistes are the doormats of the bourgeoisie.’ The music sounds like a carefree bouncy march, but it is not so simple. The audience won’t know, but it is a specific artificial counterpoint, known as species counterpoint. I’ve altered the opening measure, but you can see some elements fairly easily. The Bass line is the cantus firmus, the fixed song: F E D C D E F E D A D: the Missa L’homme arme. My opera, The Tenor’s Suite, is based on the L’homme arme. The upper voice in the march of the armed man is the same line as the cantus firmus bass, but in temporal diminution. The interior line is a further diminution with the addition of embellishing passing tones. I suppose this explanation could be shortened to: there’s more to this march than meets the ear. It is a bit of contrapuntal gamesmanship that is a commentary on ‘ars est celare artem.’ I’ve concealed the art from the listener. (Something impredicatively clever about ‘ars est celare artem’ is that it is a hidden cantus firmus which refers to itself, a melody of letters based on a very limited number of elements nested within itself. Note how ‘ars est’ becomes ‘celare’ then returns to ‘ars est’ but in the slightly modified form of ‘artem.’ It’s really just ar + es + la + re, like the F E D C (and A D) from my L’homme arme melody, which is not an accident. To quote Enzo, “Ha, Ha!” (C, F or la, re.)

“Hiding the art, I continued to construct a ‘simple’ aria. The A theme, ‘When upon the stage I strut,’ is a martial oration on Enzo’s façade, his duplicity. The audience thinks he is his character, yet simultaneously worship him as a man because they identify his performance as him. So you, SangYoung, when you play the 15 Variations and a Fugue on an Original Theme in E-flat major Op. 35 ‘Eroica;’ you, SangYoung, become for the listener: the ‘Eroica.’ You embody the art. The audience doesn’t hear the twenty years you’ve put into learning your craft. They shouldn’t. They just become, with you, the Eroica. And thus you ‘strut upon the stage,’ as does Enzo, embodying boldness, in this particular aria.

“The introduction, (consisting of the opening few sentences) ‘You may think of Art,’ is a representation of the way the audience thinks we work, how you play piano and how I compose. They think we live in a dreamy, hazy world, where there are no rules or structure or work, which is why this opening music is a dreamy tremolo, a cloud, with glimpses of light shining through (the E-flat, E-flat, E-flat D-flat sforzandi.)”

Neal Ferreira and SangYoung Kim recording'You May Think of Art' in Mechanics HallAt the recording session, SangYoung remarked that in the passage immediately preceding “Your sacrifice of forty years brings tears of laughter to my eyes.” and continuing through the second appearance of the “dreamy tremolo” introductory music, my dynamics were inadequate to express Enzo’s attitude. She was correct and the passage was adjusted to reflect her perspective. Still, something seemed wrong with the passage until we discovered together a weakness in another measure and with a little octave transposition fixed the problem. That small alteration imbued the passage with greater direction. A composer can count himself fortunate when an artist takes his work and – as opposed to surrendering to every jot and tittle – adopts the music as her own, bringing her own perspective to what was originally a solitary afflatus. Once a composer begins his decomposition, his music can finally come to life, free of an intrusive and narcissistic custody.

Neal Ferreira and SangYoung Kim recording'You May Think of Art' in Mechanics HallAt the recording session, SangYoung remarked that in the passage immediately preceding “Your sacrifice of forty years brings tears of laughter to my eyes.” and continuing through the second appearance of the “dreamy tremolo” introductory music, my dynamics were inadequate to express Enzo’s attitude. She was correct and the passage was adjusted to reflect her perspective. Still, something seemed wrong with the passage until we discovered together a weakness in another measure and with a little octave transposition fixed the problem. That small alteration imbued the passage with greater direction. A composer can count himself fortunate when an artist takes his work and – as opposed to surrendering to every jot and tittle – adopts the music as her own, bringing her own perspective to what was originally a solitary afflatus. Once a composer begins his decomposition, his music can finally come to life, free of an intrusive and narcissistic custody.

The myth of the ur-composer Orpheus culminates with his death at the hands of adoring fans: Maenads, who rip him to pieces. I can think of no greater compliment to an artist than that. In 1913, a riot of legendary proportion grew out of the premiere of Stravinsky’s monumental masterpiece, Le Sacre du Printemps. Audience members hooted, laughed, fought one another, and threw vegetables at the orchestra (which begs the question, does one prepare to attend a ballet premiere by first shopping for tomatoes?) It became impossible to hear the music, loud as it is at times, over the tumult. After intermission the police were incapable of quelling disturbances in the audience and even Stravinsky was forced to flee before the final bar. We would have lost too much great music, but could Stravinsky have had a better death than to have been torn asunder that night at the debut? As an opera composer, I know the desire to have my work evoke such a visceral response, to cause a listener to become mad as the Maenads in response to my quiet contemplation of blank pages in my studio.

When Orpheus’s bride, Eurydice, died from a snake bite before they could consummate their marriage; Orpheus descended into Hell to fetch her back. No mortal could enter hell and return to life, but Orpheus’ music was so moving, Hades himself allowed the peerless composer to return with his wife to Earth, with the single proviso that he not look back at her before their ascent to the world of the living had been realized. Orpheus couldn’t tolerate the uncertainty of Eurydice’s presence, and glancing back, seeing her face, he lost her to death a second and final time. Subsequently, the bitter Orpheus, “did utterly eschew the womankind; yet many a one desirous were to match with him, but he them with repulse did all alike dispatch. He also taught the Thracian folk a stews of males to make, And of the flowering prime of boys the pleasure for to take.”(5) Furious that Orpheus had forsaken the company of women for the carnal love of boys, a band of wild women, in the midst of a sexual frenzy, dismembered Orpheus and threw his head and lyre into a nearby river. Floating towards the Mediterranean, the disembodied head and lyre performed one last song.

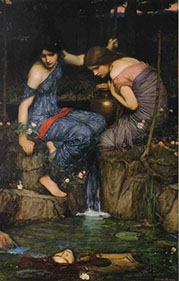

Nymphs find the head of Orpheus by J. W. WaterhouseThe image of Maenads tearing apart the great poet and musician because he is unavailable to them (either because of his turn to pederasty or for a perceived slight to the god Dionysus) is not unfamiliar to us today. I recall the Maenads of the sixties. They raved, they danced; in an ecstatic frenzy of desire for their Orpheuses: Elvis, the Beatles, the Monkees. Today the same phenomenon persists with equal fanaticism. And the parallels to the myth of Orpheus remain: the young singer/songwriter/performerwho has no wife, who appears both available and unavailable; who inspires ravenous worship from young women. The play, Der Kammersänger, by Benjamin Franklin Wedekind, revolves around an hour in the life of a famous singer, a fin de siècle Orpheus, Gerardo, in his hotel suite; wherein he is visited by three unwelcome guests. In 1979 I adapted Wedekind’s one act play, translating it into English and altering one of the principal character’s gender, in order to focus my operatic version of the story, which I titled The Tenor’s Suite, on the Orpheus metaphor. In the original play, the protagonist, whom I renamed Enzo Cesare, discovers – to his annoyance – hiding in his room, a teenage girl, who professes her love for him. I thought the girl’s infatuation with Enzo captured the spirit of Orpheus’ intoxicated fanatical Maenads. Enzo’s second visitor, a composer, represented, at least I fancied, an aspect of Enzo himself, the intellectual and aesthetic creativity which the tenor’s admirers overlooked when they evinced an adoration of the singer’s voice over the creation of the music itself; as in the way audiences in the 70’s went gaga over Luciano Pavarotti singing “Nessun dorma.” The third visitor to Enzo’s suite, Alan (Helen, in the Wedekind), is a reflection and commentary on Orpheus’ final days and death; but with Alan accepting the mantle of Orpheus’ burden of premature death.

Nymphs find the head of Orpheus by J. W. WaterhouseThe image of Maenads tearing apart the great poet and musician because he is unavailable to them (either because of his turn to pederasty or for a perceived slight to the god Dionysus) is not unfamiliar to us today. I recall the Maenads of the sixties. They raved, they danced; in an ecstatic frenzy of desire for their Orpheuses: Elvis, the Beatles, the Monkees. Today the same phenomenon persists with equal fanaticism. And the parallels to the myth of Orpheus remain: the young singer/songwriter/performerwho has no wife, who appears both available and unavailable; who inspires ravenous worship from young women. The play, Der Kammersänger, by Benjamin Franklin Wedekind, revolves around an hour in the life of a famous singer, a fin de siècle Orpheus, Gerardo, in his hotel suite; wherein he is visited by three unwelcome guests. In 1979 I adapted Wedekind’s one act play, translating it into English and altering one of the principal character’s gender, in order to focus my operatic version of the story, which I titled The Tenor’s Suite, on the Orpheus metaphor. In the original play, the protagonist, whom I renamed Enzo Cesare, discovers – to his annoyance – hiding in his room, a teenage girl, who professes her love for him. I thought the girl’s infatuation with Enzo captured the spirit of Orpheus’ intoxicated fanatical Maenads. Enzo’s second visitor, a composer, represented, at least I fancied, an aspect of Enzo himself, the intellectual and aesthetic creativity which the tenor’s admirers overlooked when they evinced an adoration of the singer’s voice over the creation of the music itself; as in the way audiences in the 70’s went gaga over Luciano Pavarotti singing “Nessun dorma.” The third visitor to Enzo’s suite, Alan (Helen, in the Wedekind), is a reflection and commentary on Orpheus’ final days and death; but with Alan accepting the mantle of Orpheus’ burden of premature death.

In his hotel suite, complete with grand piano, Enzo is attempting to practice the aria “Non piangere Liu,”(6) from Puccini’s opera Turandot, when he is interrupted by the arrival of a composer. The composer, Professor Manteau (and whom Enzo erroneously calls Mr. Mantle), wants Enzo to sing the role of Theseus in his new opera. He claims that Enzo promised to help him bring his opera to life, and pleads with the tenor to think about “Art.” Manteau’s evocation of “Art” prompts Enzo Cesare to unleash a lengthy rebuttal to the composer’s plea. “You may think of art as illuminating. You may spend your last years ruminating on the pristine chapel of your faith. You may believe, but the rest of us do not,” Enzo chides Manteau. At the premiere of The Tenor’s Suite in Philadelphia, in 1981, I sensed an unease during Enzo’s aria, and some murmurs. No fisticuffs interrupted the music, but after the curtain came down, “members of the contemporary ensemble Relache attacked Summer’s negative reference to contemporary music in the libretto. What followed was a loud debate on avant-garde music versus Summer’s Strauss-Mahler musical context, an idea so reprehensible to Relache leader Joseph Franklin that, members of the audience reported, he (Franklin) began to tear off his shirt.”(7) A gift from the gods. I was ecstatic myself that the first performance of my operatic music ended with a melee, that the director of a well known Philadelphia music institution had rent his garments in dismay at my offering. Reporter Christine Woodside queried Franklin about his reason for ripping his own shirt off. “‘Why dredge up Strauss,’ Franklin told the Welcomat . . . ‘I see no need to write in such a dated style. It’s a dead issue. Anything written in a Strauss style has already been done by Strauss.’”(8) Not only was I so fortunate to have a small, but respectable, riot at the premiere, and a newspaper article chronicling it, and a rioter admitting to his frenzied response; but even better, my principal rioter, Joseph Franklin, a fellow composer (I suppose) graciously enunciated his rationale (ex post facto) for tearing his clothes off. And, his rationale, Sacré bleu, was nearly word for word taken from my libretto! Franklin never spoke with me after his explosion that September night in a small theater on South Street in Philadelphia, but when he told the reporter “Why dredge up Strauss? I see no need to write in such a dated style. It’s a dead issue. Anything written in a Strauss style has already been done by Strauss,” I still wonder whether he was deliberately or unconsciously echoing my fictional Enzo. Did he appreciate the irony? Did he like my musical reference to Strauss? Did Franklin feel himself transported into my opera, so that it was him rather than Enzo saying, “One other thing, compositor, since Strauss’ death we’ve no need for modern scores. Why should we break our heads upon the new when Strauss has broken ribs before he bid adieu; And I do you. Adieu. Oh, if you value success then why not find what there is in Strauss and Wagner and compress the two? Perhaps you’ll win some change.” Composers should be circumspect when evaluating the works of other composers, especially when they are moved to pontificate. Puccini said of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps, “the music (is) an absolute cacophony. . . all in all, it’s the work of a madman.”(9)

Though Franklin compared my music to Strauss and Mahler, perhaps because of those lines in the libretto, or because in an interview prior to the performance I mentioned Strauss and Mahler as major influences; my music has been said to resemble Britten, Puccini, and even Schubert (though the reference to Schubert was modified, videlicet: “a psychedelic Schubert”). I understand that critics wish to place my music in a context, for the prospective listener, and won’t argue. My own estimation is that I find Beethoven and Bartok to be my primary sources for musical enlightenment, but, indeed, the Mahler and Strauss influence is undeniable. The reason I referred to Strauss and Wagner in the “You may think of art” aria from The Tenor’s Suite wasn’t because I thought I owed them any special homage, but rather because of how I understood them within the framework of the Orpheus myth. Like Orpheus, they both wrote their own music and text (Wagner all, Strauss some. I’ve written my own libretti, with the exception of my Shakespeare operas, Hamlet and The Tempest). In the Art aria from my The Tenor’s Suite, Enzo reports that:

“When upon the stage I strut,

Shrieking Siegmund’s obscene rot,

You may be assured that not one person there

Takes the slightest interest in our little drama.

If they did, how could they listen

To the Walküre’s strident messages

Of lust and incest heaped upon another?

Yet, in their third row seats

There sits a mother,

Smiling on her teenage daughter.

If she but heard my words

She’d smile no longer.”

There is often a cognitive dissonance between the composer and audience. My reference to the “teenage daughter,” and Die Walküre (above) is my parody of J.P. Morgan’s daughter and the ill-contrived offense she took at Salome in the midst of endless Ring of the Nibelung obscenity. Strauss’ Salome was roughly withdrawn after its 1907 New York Metropolitan Opera premiere following just the first performance. The next three scheduled performances were cancelled because J. P. Morgan’s daughter, repulsed by the opera, went “in a fury” to her father, the powerful fin-de-siecle financier and Metropolitan Opera board member, and demanded daddy kill Salome.(10) The irony of the daughter of (arguably) America’s King demanding the death of Strauss’ pious opera escaped the commentators of the time, focused as they were on the lasciviousness of the character Salome; missing, evidently, the orthodox treatment of the story which even Kaiser Wilhelm II, nominal leader of the Protestant church in Germany, had allowed. Why not rail against the popular lickerish Met offerings such as Die Walküre, in which its author Wagner panegyrizes Siegmund, the murderous, incestuous adulterer? When the Morgan clan attended Wagner’s immoral tetralogy, did J.P. Morgan’s wife smile at her adolescent offspring?

Whereas J.P. Morgan was not literally the king of America; Henry VIII was the literal king of England, and he was memorialized (if blandly and tediously) by the literary king of English, William Shakespeare, perhaps. The play The Life of King Henry the Eighth has numerous elements that point to other authors than Shakespeare to whom it is attributed. Act III of the propagandistic The Life of King Henry the Eighth begins with a command from Queen Katherine to one of her servants, “Take thy lute, wench: my soul grows sad with troubles; Sing, and disperse ‘em.” The wench (an early example of music therapist) obliges and sings of Orpheus in trochaic octameter (and not in iambic heptameter, as the text is often mislabeled. The confusion is due to the empty eighth beat at the end of several lines, but iambic heptameter begins with an unstressed syllable as opposed to trochaic octameter). Shakespeare wrote primarily in iambic pentameter. It is now believed by many experts that John Fletcher was a collaborator with Shakespeare on The Life of King Henry the Eighth and that the song, Orpheus with his Lute made Trees, rhythmically different from Shakespeare’s proclivities, is Fletcher’s work.(11) I find it interesting as well that the rest of the scene continues in a somewhat tortured classic Greek trochaic hendecasyllable. Maybe the author(s) wanted to elevate their setting to the level of ancient Greek drama, Henry VIII as an Hellenic hero; rather than the brute Tudor monster he was. Numerous composers have set the text to the wench’s song. The musical legacy of the eighteenth century British composer, Thomas Chilcot, consists of nothing more than a handful of works for harpsichord, and one outstanding collection of vocal music accompanied by orchestra titled: Twelve English Songs with their Symphonies; set to Shakespeare, Marlowe, Euripides, and Anacreon (the latter two in translation.) When I ran across this obscure collection I was struck by two things, the first being that Chilcot and I shared an affinity for the same writers. Besides my ever growing collection of Shakespeare settings, I’ve written a grand opera based on Euripides’ Hippolytus, and set a few Marlowe poems. (I think Marlowe’s poetic voice is superior to Shakespeare, but Shakespeare is head and shoulders above Marlowe when it comes to playwriting). Anacreon I do not hold in such high esteem as does Chilcot, but I did manage to insert an Anglicized Anacreontic chorus into Hippolytus. The other thing that I found intriguing was that his Orpheus with his lute sounded not unlike my setting of Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer’s Day: solo flute and female voice accompanied by insouciant pizzicato.(12) The use of flute, by Chilcot, rather than lute, demanded I refer to the work as “Orpheus with his (f)Lute,” in all my preplanning correspondence with Arcadia Players’ music director, Ian Watson.

Composers really begin to live only after they die, and often compose with the anticipation that what they are doing in the present will only be apprehended in the future. Their compositions are perceived as memories and anticipations (with the exception of dance music, which exists in the here and now). Listening to music we employ one ear to look behind and the other to look ahead; the present always an ephemeral instant. So composers, who live, are acutely aware that they are ephemeral, too; and that they labor at ornate mausoleums of their craft. We spend our entire lives building a tomb to hold our contemplation of the end. Sadly for Chilcot, who expired suddenly and unexpectedly, none of his post mortem plans were realized because of a battle over his estate. Most of his music, except for a few eloquent orchestral songs and some harpsichord etudes and concerti, have not survived. That his funeral procession and music did not go off as he himself had planned is no tragedy, but that his oratorio Elfrida is lost is. It was described as his best work.

I’ve not planned my own funeral procession, but I have written a song about my demise which is meant to capture my wife’s mourning. I don’t know how to properly describe the strange hubris of my setting of “On the death of Phillips.” The anonymous text “bewails” the death of a 16th-century lutenist, a 16th-century Orpheus, whose loss is felt most poignantly by his beloved: his lute. “The lowering lute lamenteth now therefore Phillips her friend that can her touch no more.” Occasionally I include notes in my musical score, but very infrequently. I include two for “On the Death of Phillips.” The first reads: “The brief horn passage at measure 59 begins with a musical quotation from the first of Twenty-Two Duets for French Horns (1968) by Alec Wilder. My wife, Lisa, and I played the duet together frequently when we were children.” On this recording a cello plays the role of the horn. Perhaps the horn should only play this snippet when my “hand is cold.” The second note pertains to a request I made on staging a live performance. I request that: “Next to the French hornist, place a chair. On the chair, place an old and battered French horn, such as my ancient Krüspe. If a hornist is not employed, and the clarinetist [or cellist] plays the horn cues, it is still preferred that a horn be placed on a chair on stage.” I can only defend my elaborate mourning of my own death as a posthumous love letter to my beloved Lisa. We met in orchestra, in 1970, as children, playing horn side by side; and as our Platonic friendship continued for seven years we were always sitting beside each other, horns to our lips, making music. We played duets, mostly Bach inventions, and I reveled in the interweaving of the musical lines therein. The first of the Alec Wilder duets we played often, mostly because I was best at playing loudly in the upper register and with crude brutality. The Wilder duet allowed me to express my callowness fully. Never having outgrown my callow youth, I composed “On the Death of Phillips,” for my wife, for her to remember with happiness my boyish boisterous love for her that after long years matured, a little, at least enough for her to agree (through Machiavellian machination on my part) to “wrest (her) pleasant notes into another sound;” that other sound being “I do,” rather than those earlier uglier (to me) demurrals.

Lisa Summer at the Swann Fountain in Philadelphia (1972)-.jpg) This disc contains enhanced content, beyond the audio portion, including my “electronic” Retrograde Requiem. At the Oberlin College Conservatory, in the early seventies, I studied “acoustics and technology” as well as the standard repertoire of music theory and history. During my sophomore and junior years I crafted – I don’t want to say “composed – several “electronic” pieces. I use quotation marks around the word “electronic” because I want to differentiate these from compositions created on synthesizers or wholly electronically. What my pieces were were a genre of composition now defunct, called Musique concrète. Pioneered in the forties by Pierre Schaeffer and originally a part of the French Resistance movement, in the fifties Musique concrète had come to attract the attention of serious composers such as Olivier Messiaen, Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Iannis Xenakis, Michel Philippot, Arthur Honegger, and Edgard Varèse. The latter composer was my model for my own attempts at Musique concrète, in particular his “Poème électronique.” Before matriculating at Oberlin I had heard examples of Musique concrète and discussed it with my neighbor, F. G. Asenjo. The Asenjo family and my own lived in Forbes Terrace, a collection of row homes in Squirrel Hill, Pittsburgh. On occasion I would stop by his home and talk about my progress as a composer. He was a professor of mathematics at the University of Pittsburgh, and a composer of some accomplishment, as well. He thought my interest in electronic music was a waste of my time. “Although (electronic music’s) potential is enormous, its advocates show a lack of musical aim that has led to a general lack of articulation, with the result that today (1971) electronic music is not properly a language but rather a haphazard catalog of uneventful bursts and undulations,” he wrote.(13) That sentiment he had expressed to me in person during many of my visits with him across the thin strip of lawn and trees that separated the left from the right rows at Forbes Terrace. I had thought about his comments often, and even kept the essay from which I have plucked that quote – a stapled blue covered reprint he put in my hands – throughout my days at Oberlin. When I began creating my electronic music, I crafted Retrograde Requiem as one would a sonata. I wrote out the music, and then recorded the passages on various instruments myself: piano, French horn, xylophone, and a few other pitched percussion. Subsequent to the recording, I filtered, cut, and taped the recordings into the order I had preplanned (while also altering the sounds with more filters and playback reverb.) This is why, for example, when the Dies Irae appears it sounds correct but the envelopes of the piano are reversed. Writing out the Dies Irae in reverse, and then playing it as rewritten, allowed me to simply cut the tape and turn it around to create a reverse envelope. Retrograde Requiem is a reflection on the Orphic victory over death, but by a very young and naïve composer. I was caught between crafting a contemplation on mortality and music and my response to Asenjo’s criticism and commentary. “If music is to be judged by the effect it produces and not by the language it uses, the artist should give priority to this effect, reflecting on its nature above any other consideration. For ultimately, it is through the search for new experiences that originality develops.” [ibid] Retrograde Requiem may not be an original or compelling work, but its creation was part of my youthful journey through “new experiences” that allowed me to see elements of musical construction from a different perspective; and I hope, eventually write something original.

This disc contains enhanced content, beyond the audio portion, including my “electronic” Retrograde Requiem. At the Oberlin College Conservatory, in the early seventies, I studied “acoustics and technology” as well as the standard repertoire of music theory and history. During my sophomore and junior years I crafted – I don’t want to say “composed – several “electronic” pieces. I use quotation marks around the word “electronic” because I want to differentiate these from compositions created on synthesizers or wholly electronically. What my pieces were were a genre of composition now defunct, called Musique concrète. Pioneered in the forties by Pierre Schaeffer and originally a part of the French Resistance movement, in the fifties Musique concrète had come to attract the attention of serious composers such as Olivier Messiaen, Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Iannis Xenakis, Michel Philippot, Arthur Honegger, and Edgard Varèse. The latter composer was my model for my own attempts at Musique concrète, in particular his “Poème électronique.” Before matriculating at Oberlin I had heard examples of Musique concrète and discussed it with my neighbor, F. G. Asenjo. The Asenjo family and my own lived in Forbes Terrace, a collection of row homes in Squirrel Hill, Pittsburgh. On occasion I would stop by his home and talk about my progress as a composer. He was a professor of mathematics at the University of Pittsburgh, and a composer of some accomplishment, as well. He thought my interest in electronic music was a waste of my time. “Although (electronic music’s) potential is enormous, its advocates show a lack of musical aim that has led to a general lack of articulation, with the result that today (1971) electronic music is not properly a language but rather a haphazard catalog of uneventful bursts and undulations,” he wrote.(13) That sentiment he had expressed to me in person during many of my visits with him across the thin strip of lawn and trees that separated the left from the right rows at Forbes Terrace. I had thought about his comments often, and even kept the essay from which I have plucked that quote – a stapled blue covered reprint he put in my hands – throughout my days at Oberlin. When I began creating my electronic music, I crafted Retrograde Requiem as one would a sonata. I wrote out the music, and then recorded the passages on various instruments myself: piano, French horn, xylophone, and a few other pitched percussion. Subsequent to the recording, I filtered, cut, and taped the recordings into the order I had preplanned (while also altering the sounds with more filters and playback reverb.) This is why, for example, when the Dies Irae appears it sounds correct but the envelopes of the piano are reversed. Writing out the Dies Irae in reverse, and then playing it as rewritten, allowed me to simply cut the tape and turn it around to create a reverse envelope. Retrograde Requiem is a reflection on the Orphic victory over death, but by a very young and naïve composer. I was caught between crafting a contemplation on mortality and music and my response to Asenjo’s criticism and commentary. “If music is to be judged by the effect it produces and not by the language it uses, the artist should give priority to this effect, reflecting on its nature above any other consideration. For ultimately, it is through the search for new experiences that originality develops.” [ibid] Retrograde Requiem may not be an original or compelling work, but its creation was part of my youthful journey through “new experiences” that allowed me to see elements of musical construction from a different perspective; and I hope, eventually write something original.

1) I am reminded of a story my Oberlin mentor, Richard Hoffmann, told me of Schönberg when he acted as the father of serialism’s amanuensis. Schönberg had heard on the radio of an upcoming broadcast of a Ralph Vaughan Williams piece and asked Hoffmann whether “Von Wilhelm” was a fellow Austrian. (Keep in mind, too, that Vaughan Williams’ first name is pronounced rafe as in safe). (back)

2) Hank Whittemore, author of The Monument, concerning the Shakespeare sonnets and their relation to the bard’s ipseity, is a frequent writer on the authorship question. Of his “100 Reasons Why Oxford was Shakespeare,” Golding is the second (of the hundred.) http://hankwhittemore.wordpress.com/category/hanks-100-reasons-why-oxford-was-shakespeare-the-list-to-date/ (back)

3) William Butler Yeats wrote his poem, “Leda and the Swan” in the form of a sonnet, a structure made famous by Shakespeare, but first championed in England by Sir Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard, the Earl of Surrey (and Edward DeVere’s uncle). (back)

4) The sound of coughing in this recording following the lines, “They throw their flowers and money like they wipe their feet, Without a single thought in their great vacuous heads,” is not an error in editing. We didn’t leave in Neal coughing either purposefully nor accidentally. The cough is in the score, and is part of the story line. Here’s the stage direction: (He coughs). (back)

5) All quotations from The Metamorphoses are verbatim from the Arthur Golding translation. This one is from The Song of Orpheus (back)

6) I chose “Non piangere Liu,” deliberately to oppose the expectation of “Nessun dorma.” (back)

7) “Can this man start an opera company” by Christine Woodside; Welcomat, March 3, 1982; Philadelphia PA (back)

8) Ibid (back)

9) Puccini: His Life and Works, by Julian Budden, 2002; page 342 (back)

10) “The Salome Scandals of 1907” by John Yohalem; Opera News 68, no. 9 (2004): 34-36 (back)

11) Another well known Shakespeare song, “Take O Take these lips away,” is also now also believed to be the work of Fletcher by many scholars. (back)

12) For The Shakespeare Concerts 2013 debut of the Chilcot, I paired it with my similar setting of Sonnet XVIII, “Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer’s Day.” (back)

13) "The Crisis in Western Music and the Human Roots of Art" by F. G. Asenjo; Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, XXIX / 4, Summer 1971 (back)

© NAVONA RECORDS LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

info@navonarecords.com

www.navonarecords.com

223 Lafayette Road

North Hampton NH 03862

Navona Records is a PARMA Recordings company