Of Piano Sonata No. 17 in D minor, Op. 31, No. 2; Beethoven’s secretary and biographer, Anton Schindler, asked the maestro what the magnificent creation meant. “Lesen Sie nur Shakespeare’s Sturm,” Beethoven curtly replied. (Read Shakespeare’s Tempest!). Schindler is unreliable, prone to flights of fancy concerning the composer; and often, even when his facts are straight, his interpretations are questionable. Schindler famously reports that when he asked Beethoven why the great 32nd sonata had only two movements, the composer replied that he didn’t have the time to write a third; a response which we would be right to assume was simply snarky or dismissively cruel, and certainly not true.(1) So, when we contemplate Ludwig’s command to Schindler, “Lesen Sie nur Shakespeare’s Sturm,” we can’t assume too much. Schindler was not an intimate of Beethoven when the piece was in progress, and the remark was made two years after the final bars had been written.

I don’t want to imagine Schindler as a mendacious slave to the overbearing Beethoven, a Caliban to his Prospero. “Thou most lying slave, Whom stripes may move, not kindness! I have used thee, Filth as thou art, with human care, and lodged thee in mine own cell,” nor to elevate Schindler from amanuensis to faithful servant, an Ariel attiring him before his appearance amongst the mortals. “Why, that's my dainty Ariel! I shall miss thee: But yet thou shalt have freedom.” I assume Schindler occupies a middle ground, and that we can reasonably lend credence to the gist of “Lesen Sie nur Shakespeare’s Sturm,” videlicet: the sonata is indeed informed by The Tempest. It wouldn’t be the first nor last time the play inspired a composer. The 1991 edition of the Gooch and Thatcher compendium of music set to Shakespeare has 1,607 entries for the play; the plurality of which center on Ariel, the play’s aerial spirit, whose song “Full Fathom Five” has garnered the most attention from the most composers. Mendelssohn, whose incidental music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream is the best musical interpretation of Shakespeare, considered setting The Tempest as an opera three times, twice contracting for the libretti; first in 1833 with Karl Immermann, and again in 1847 with Eugene Scribe. The composer found both libretti wanting, and chose not to proceed. (Another attempt, between the Immermann and Scribe, was explored with W. R. Griepenkerl, but was aborted prior to the completion of the libretto). In 1983, one hundred fifty years after Mendelssohn abandoned his first Tempest, I had a dream – “past the wit of man to say what dream it was: man is but an ass, if he go about to expound this dream. . . The eye of man hath not heard, the ear of man hath not seen, man's hand is not able to taste, his tongue to conceive, nor his heart to report, what my dream was.” – I dreamt the music to the overture to The Tempest Mendelssohn didn’t write. It wasn’t quite Mendelssohn, however, as during my dream I was informed that it was the Tempest overture by Mendelssohn, as influenced by Wagner; an unlikely direction as Mendelssohn preceded Wagner, and might have been rather distraught at Wagner’s attacks upon him, had he been alive to read them. As it happened, Wagner, the braying coward, published his assault on Mendelssohn anonymously, and after Mendelssohn’s death. “He has shown us, that a Jew may possess the greatest abundance of specific talents, the finest and most diverse education, the most elevated, delicately perceptive sense of honor – and yet in spite of all these advantages, never once be able to summon the profound rending of heart and soul that we expect from music.” This passage from Wagner’s Jewishness in Music, his seminal anti-Semitic screed, is an embarrassing legacy from a composer whose popular wedding march (from Lohengrin) is nearly as moving as the nonpareil wedding march by Mendelssohn (from A Midsummer Night’s Dream.) After waking from my dream, I told my wife Lisa about it, and she asked me to write out the music. I protested that it was simply a meretricious unconscious theft of Mendelssohn, with a soupçon of Wagner; writing it out would be of no value, but I relented about preserving the concept of the dream and sketched the first measures.

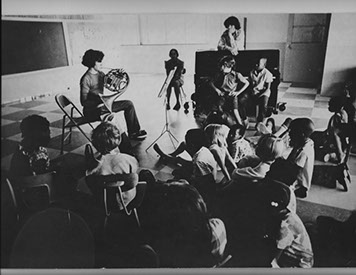

Opening bars to the dreamt Tempest overtureWhereas Mendelssohn approached The Tempest three times, and withdrew an equal amount, I approached it many more times until finally – and most recently – submerging myself in its completion. My first encounter was not direct, rather a shadow of an inkling, a juvenile opera I penned when I was seven, titled Ship of Doom. It wasn’t really an opera, as I forgot to include any words; and it wasn’t really Shakespeare. It did have a storm and a sinking ship. It wasn’t until I was fourteen that I thought of Shakespeare’s The Tempest again as a source for musical inspiration. During the summer of 1970 I traveled from my home in Pittsburgh PA, to study French horn at the Eastern Music Festival (EMF), a summer music camp in North Carolina. Besides bringing my ancient Krüspe double horn, which I had purchased with money I earned previously working as a stock boy in a Pittsburgh men’s fashion boutique, The Gallery Clothes Bar; I also brought some music I had recently composed for chamber ensembles. One afternoon while rehearsing with some fellow campers a brass ensemble work I’d written, we were visited by the EMF director, Sheldon Morgenstern, who was accompanied by a visiting guest conductor from Czechoslovakia, Otakar Trhlik. Trhlik and Morgenstern remained for the duration of the rehearsal. As we began to pack our instruments into their cases, Trhlik pulled me aside and asked me some questions, questions I can no longer recall. I was fourteen years old. All I remember is that he seemed delighted with my music, which was – I felt at the time – puzzling. True, I had been composing for years, and had received some mild approbation from a few, but Trhlik was beaming. The conductor wanted to have the score of my music which we’d been rehearsing, and Morgenstern took my score so that a copy could be made. (What Trhlik did with the score, I’ve no idea; I never spoke with nor heard from him again.)

Opening bars to the dreamt Tempest overtureWhereas Mendelssohn approached The Tempest three times, and withdrew an equal amount, I approached it many more times until finally – and most recently – submerging myself in its completion. My first encounter was not direct, rather a shadow of an inkling, a juvenile opera I penned when I was seven, titled Ship of Doom. It wasn’t really an opera, as I forgot to include any words; and it wasn’t really Shakespeare. It did have a storm and a sinking ship. It wasn’t until I was fourteen that I thought of Shakespeare’s The Tempest again as a source for musical inspiration. During the summer of 1970 I traveled from my home in Pittsburgh PA, to study French horn at the Eastern Music Festival (EMF), a summer music camp in North Carolina. Besides bringing my ancient Krüspe double horn, which I had purchased with money I earned previously working as a stock boy in a Pittsburgh men’s fashion boutique, The Gallery Clothes Bar; I also brought some music I had recently composed for chamber ensembles. One afternoon while rehearsing with some fellow campers a brass ensemble work I’d written, we were visited by the EMF director, Sheldon Morgenstern, who was accompanied by a visiting guest conductor from Czechoslovakia, Otakar Trhlik. Trhlik and Morgenstern remained for the duration of the rehearsal. As we began to pack our instruments into their cases, Trhlik pulled me aside and asked me some questions, questions I can no longer recall. I was fourteen years old. All I remember is that he seemed delighted with my music, which was – I felt at the time – puzzling. True, I had been composing for years, and had received some mild approbation from a few, but Trhlik was beaming. The conductor wanted to have the score of my music which we’d been rehearsing, and Morgenstern took my score so that a copy could be made. (What Trhlik did with the score, I’ve no idea; I never spoke with nor heard from him again.)

14 year old Joseph Summer playing horn for Project LISTEN,in North CarolinaBefore returning to the Eastern Music Festival in the summer of 1971, one of EMF’s resident professional musicians met me at the Centers for Musically Talented in Pittsburgh and informed me that Sheldon Morgenstern had recommended that besides French horn, my principal area of study, I would have an opportunity to study composition, based on the recommendation of the previous year’s guest conductor, Otakar Trhlik.

14 year old Joseph Summer playing horn for Project LISTEN,in North CarolinaBefore returning to the Eastern Music Festival in the summer of 1971, one of EMF’s resident professional musicians met me at the Centers for Musically Talented in Pittsburgh and informed me that Sheldon Morgenstern had recommended that besides French horn, my principal area of study, I would have an opportunity to study composition, based on the recommendation of the previous year’s guest conductor, Otakar Trhlik.

A few weeks into the summer session at EMF, Morgenstern introduced me to Karel Husa, 1971’s visiting composer/conductor. Husa was a towering, massive presence. He looked to me like the prototype for the true maestro. I was barely over five feet tall at the time and couldn’t have weighed more than nine stones. Forewarned by Morgenstern, I had brought all of my musical compositions for Husa to review. Alone in an office with this enormous man, I watched him peruse my scores for half an hour. Neither of us said anything. He would pick up a score, scan it, sometimes quickly, sometimes with slow deliberation. Eventually, he spoke. “You must make a decision, do you want to be a French hornist or a composer?”

I was a fairly awful hornist, but I had hoped that someday I would finally overcome my foibles and find a career in a symphony orchestra. Composing was, I had assumed, something that could be accomplished simultaneously with a career as a hornist. Husa demanded a decision, and it seemed evident that this Titan would have me choose composition. Obediently, I responded that I would be a composer. “Good,” he said, matter-of-factly. “Now, take this,” he said, pointing at the pile of my music, “and burn it, all of it. We start again, two voices, learning from Bartok.”

I must have said something, but I suppose it was only some acquiescent agreement to the pyre. He took one of my sketch pads, blank, and wrote out three bars of a simple ¾ melody, instructing me to compose a piece for two voices only, with Bartok as my model.

That evening I took the pile of music, music which I had written over the three previous years, including the piece Husa’s Czech compatriot, Otakar Trhlik, had found worth photocopying, and in a fireplace on the Guilford College Campus (where the Eastern Music Festival resided) burned everything: symphonies, horn concerti, sundry pieces for brass instruments. I watched them reduce to ash, in a state of disjuncture from my emotions. No tears. Husa was right. It was all worthless. The next weeks I worked on four two voice compositions for oboe and bassoon, and then, with Husa’s approval, some three voice works. He took the four two voice compositions, and on his own, recruited an oboist and bassoonist. Without my presence, he rehearsed the duets, and then, in a gesture that even I found perplexing, conducted them, conducted an oboist and bassoonist, in concert, during what was otherwise a symphonic concert at Dana Auditorium on the Guilford College campus in Greensboro, North Carolina. I was overwhelmed with gratitude; but the sight of this immense man, directing two young women alone in my duets, while the orchestra sat silently on stage for eight minutes, still leaves me wondering at his magnanimity and the remarkable way he executed it.

Of those two and three voice compositions I wrote under Husa’s tutelage, a few seemed meritorious long after I inked them. “Where the bee sucks,” scored for oboe, bassoon, and mezzo-soprano – with the exception of eight bars near the end, and an alteration of instrumentation to facilitate its performance by the Lunar Ensemble – appears on this recording just as I wrote it at Eastern Music Festival, for Karel Husa’s approval .

Sir Michael Tippett set three Ariel arias as incidental music for a production of The Tempest at the Old Vic Theatre in London, in 1962. There are numerous incarnations of them, one for chamber ensemble, one for piano, one for harpsichord, and eventually Tippett modified the music for two more works, the opera The Knot Garden and the Songs for Dov. The arias are “Come unto these yellow sands,” “Full fathom five,” and “Where the bee sucks.” I can empathize with Tippett’s frequent reappropriation of his own music. My setting of “Full fathom five” for mezzo-soprano, tenor, and piano; is based on the music from the B section of my “Where the bee sucks.” In addition, I inserted a thirty measure variation of the B section between the first iteration of the line “Of his bones are coral made,” and its second appearance. Thus I first wrote “Where the bee sucks” in 1971 for oboe and bassoon; then reworked it for the same instruments and a mezzo-soprano; reused it for my composition of “Full fathom five” in 2001; after adding eight measures to the original “Where the bee sucks” in the year 2000; revised and orchestrated both “Where the bee sucks” and “Full fathom five” for inclusion in my recently completed chamber opera, The Tempest. Then, a couple months ago, I took the 2000 version of “Where the bee sucks” and changed the oboe and bassoon to violin and cello, just for this recording, because the LUNAR Ensemble didn’t have an oboist and bassoonist. I really wanted the ensemble to use a flute and clarinet, so I changed four measures and wrote a version for that ensemble as well, but that particular transformation hasn’t been performed.

When I speak of composing at the age of fourteen and fifteen, I’m not bragging. Most composers score much greater successes and produce much more successful scores than did I as a teenager. Mendelssohn and Mozart, though exceptionally brilliant, were not a unique phenomenon. Most composers start young. I think there’s something interesting in the fact that there are no child prodigies in literature, but there are a myriad in music. Thomas Linley the Younger, the third child in an extraordinarily musical and star-crossed family, was born in 1756, the same year as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart; and his career mirrored the German genius. A violin prodigy, he played in public from the age of seven, appeared in musical theater: singing, dancing, and playing his instrument. In 1768 he went to Italy to study composition, meeting and befriending Mozart in April of 1770. An anonymous painting, made in 1770, shows Mozart and Linley, playing together in Florence, Mozart at the keyboard and Linley on violin. (The family in the painting is that of Gavard des Pivets).

Mozart and LinleyLinley composed music for a revival of The Tempest which was premiered shortly after its completion but not before Linley’s tragic drowning at the age of 22, the result of a boating accident, months before the premiere. (Having completed my Tempest opera and already successfully surmounted an ironic Tempest/drowning hazard; I’m hopeful that I will survive to hear the premiere of my work). The words to “O Bid thy Faithful Ariel Fly,” were not Shakespeare’s, but rather those of the producer Richard Sheridan (Linley’s brother-in-law!), the Irish playwright and owner of the Theatre Royal in Drury lane. The poetry Sheridan provides is simply awful. Jaw-droppingly bad. “Come Unto These Yellow Sands” is stripped of all but two and a half (mangled) lines of Shakespeare’s actual text, settling instead for a lengthy setting of the word “bear,” from a line interpolated by, in all probability, Sheridan, who must have thought his evisceration of Shakespeare’s text a fabulous idea. Perhaps Sheridan was mocking Shakespeare’s most notorious stage direction, “Exit, pursued by a bear” from A Winter’s Tale. Sheridan’s text for “Come Unto these Yellow Sands” consists of four metrically incompatible lines:

Mozart and LinleyLinley composed music for a revival of The Tempest which was premiered shortly after its completion but not before Linley’s tragic drowning at the age of 22, the result of a boating accident, months before the premiere. (Having completed my Tempest opera and already successfully surmounted an ironic Tempest/drowning hazard; I’m hopeful that I will survive to hear the premiere of my work). The words to “O Bid thy Faithful Ariel Fly,” were not Shakespeare’s, but rather those of the producer Richard Sheridan (Linley’s brother-in-law!), the Irish playwright and owner of the Theatre Royal in Drury lane. The poetry Sheridan provides is simply awful. Jaw-droppingly bad. “Come Unto These Yellow Sands” is stripped of all but two and a half (mangled) lines of Shakespeare’s actual text, settling instead for a lengthy setting of the word “bear,” from a line interpolated by, in all probability, Sheridan, who must have thought his evisceration of Shakespeare’s text a fabulous idea. Perhaps Sheridan was mocking Shakespeare’s most notorious stage direction, “Exit, pursued by a bear” from A Winter’s Tale. Sheridan’s text for “Come Unto these Yellow Sands” consists of four metrically incompatible lines:

“Come unto these yellow sands,

And there take hands;

Foot it featly here and there,

And let the rest the chorus bear.”(2)

As awful a rending (“rendering” being too kind a word) of the original as that is, Sheridan’s text to “O Bid Your faithful Ariel Fly,” is worse, in that it is longer and contains anserine absurdities:

“O bid your faithful Ariel fly

To the farthest Indies’ sky

And then at thy afresh command,

I’ll traverse o’er the silver sand,

I’ll climb the mountains, plunge the deep,

I like mortals never sleep,

Whate’er it be

Not with ill will,

But merrily."(3)

Leaving aside “farthest Indies’ sky,” did Sheridan forget the yellow sands when he penned this turgid verse? “I’ll traverse o’er the silver sand.” No, no Ariel won’t. When I first read through the score I became obsessed with the line “I like mortals never sleep.” I’ve considered it countless times. I think he meant to write (or should have) “Unlike mortals I ne’er sleep.” Though, I have lost sleep after reading that fragment, thinking about it overmuch. I should have given up, as Sheridan appears to have done in the succeeding three lines, “Whate’er it be not with ill will, but merrily.” Que sera, sera; as Marlowe said.

The Linley works on this recording are performed by the Arcadia Players, under the direction of Ian Watson, on instruments contemporaneous to the period of their composition. Had Linley lived to hear the premiere of his Tempest incidental music, he would have heard exactly what we offer on this recording. In 1784, six years after Linley drowned, Mozart remarked to the English musician Michael Kelly that "Linley was a true genius" who "had he lived, would have been one of the greatest ornaments of the musical world." There’s a painful irony, Mozart’s “had he lived.”

Had Stravinsky lived one more year, I would have met him. During the spring of 1970, a few months before meeting Otakar Trhlik, I met Carl Bewig, at the Centers for the Musically Talented on Fifth Avenue in the Hill District of Pittsburgh.(4) Carl Bewig, a recruiter for Oberlin College, met with me at the Centers and informed me that I would attend Oberlin College’s music conservatory. The Centers’ director, Mihail Stolarevsky, seconded Bewig’s assertion. I accepted this. Why wouldn’t I? Like Husa after him, Bewig’s questions seemed to me more like decrees. “Joey, I hear Stravinsky is your favorite composer. Would you like to meet him?” Of course I wanted to meet him. “He’ll be at Oberlin in two years, and you will be a freshman then and will meet him.” Stolarevsky spoke to Bewig, letting him know I would still be in high school. Bewig returned his attention to me and informed me that I wouldn’t need to finish high school, that I would just matriculate at Oberlin in 1972. “Also, you should join some clubs next year, not just musical organizations, the student council, things like that,” he admonished.

When I was 15 I took a bus to Ithaca NY, to meet with Karel Husa and ask whether I might study with him at Cornell. He strongly discouraged me, recommending instead I go to a conservatory. I told Husa that Oberlin College had already informed me that I could attend the conservatory on a full scholarship, and Maestro Husa approved, suggesting I see him again when I’d graduated. With his blessing, I called Bewig at Oberlin, said I was ready; and the school made good on all the promises that Bewig had made me, except one: Stravinsky died before his scheduled visit to Oberlin, so I never met the 20th century’s greatest composer.

The first full score I ever owned was the Carmina Burana by Carl Orff, the second was Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. To this day I remember the first time I heard the work. I was at the Syria Mosque in Oakland, not too far from Forbes Field, where the Pittsburgh Pirates played. The Pittsburgh Symphony was playing at the Mosque, William Steinberg was conducting. I knew a lot of the standard repertoire from the 18th and 19th century but had never experienced anything like Le Sacre du Printemps. Every measure was an epiphany. Early in the masterpiece, I saw bubbles rising from the viola section, a moment of scintillating synesthesia. It wasn’t “as if” I saw bubbles rising from the orchestra, I saw them plain as day. I knew, as I watched, that what I was seeing I wasn’t seeing, and in a thrice the consciousness of the reality ended the wondrous hallucination. Immediately after the concert I told my “stepfather,” Maynard Duncan, that I needed the score. The next week we traveled to Volkwein’s, Pittsburgh’s enormous music store in the nineteen sixties, to obtain it. It was $5.00, marked up from $4.50. Thank goodness Maynard had the cash. When we got home I began to read and hear the music.(5) Reaching the moment in the score where I had seen the illusory bubbles, I saw them again, tiny veridical bubbles floating above the viola part. To my surprise and delight, I learned that these bubbles were the way composers indicated natural harmonics for string instruments. Stravinsky had written a series of harmonic glissandi on the viola C string, creating an effect I’d never heard, and which I had coincidentally experienced as an emerging cascade of bubbles. My barmy imagery had an ex post facto rationalization.

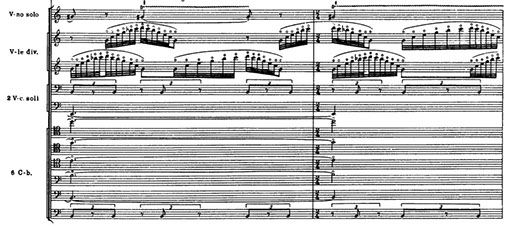

Viola natural harmonic arpeggios from Le Sacre du printempsI have never stopped being transfixed by the music of Stravinsky since that first experience with Le Sacre du Printemps. At Oberlin I studied every single piece he had published, though I wasn’t enamoured of most of his works written after Schönberg’s death in 1951. One exception in regard his post Schönberg works, though, was his Three Songs from William Shakespeare, for mezzo-soprano, flute, clarinet, and viola; written in 1953. I can’t explain why these three angular arias appeal so much to me, but they occupy a large part of my music consciousness. There’s not a day that goes by in my life that I don’t hear in my mind’s ear a portion of Stravinsky’s Renard, a burlesque for 4 pantomimes and chamber orchestra (written in 1916); and there are dozens of other Stravinsky works that captivate me more than Three Songs from William Shakespeare; but none of his others took such a strong hold on my compositional strategies that I was compelled to compose so many pieces in its reflection. I’ve written nine or ten works for voice(s), flute, clarinet, and viola – a ridiculous ensemble – as a kind of post-mortem epistolary conversation with Stravinsky. Most of my music I think of as letters to dead composers, fan letters, in which my compositions are questions or – when I feel so bold – answers to the masters I revere. I’ve written eight “books” of music set, mostly, to Shakespeare texts, which I call the Oxford Songs. Most of the twelve stories in Book VI are scored for voice, flute, clarinet, and viola. They are all messages to Stravinsky, stories of my admiration and love for his music, and my attempt to ask him – through music – his opinions. On this recording appear “I do not know one of my sex,” “O Mistress mine,” and “Love, what thing is love,” three selections from Book VI. Oh, I forgot, and “Before you can say come and go,” which is a fifteen second setting of a breathless Ariel, appealing to Prospero for approval. So, make that four stories from Book VI. My setting of “Full Fathom Five” is not from this book, but is the twelfth chapter of Oxford Songs Book III.

Viola natural harmonic arpeggios from Le Sacre du printempsI have never stopped being transfixed by the music of Stravinsky since that first experience with Le Sacre du Printemps. At Oberlin I studied every single piece he had published, though I wasn’t enamoured of most of his works written after Schönberg’s death in 1951. One exception in regard his post Schönberg works, though, was his Three Songs from William Shakespeare, for mezzo-soprano, flute, clarinet, and viola; written in 1953. I can’t explain why these three angular arias appeal so much to me, but they occupy a large part of my music consciousness. There’s not a day that goes by in my life that I don’t hear in my mind’s ear a portion of Stravinsky’s Renard, a burlesque for 4 pantomimes and chamber orchestra (written in 1916); and there are dozens of other Stravinsky works that captivate me more than Three Songs from William Shakespeare; but none of his others took such a strong hold on my compositional strategies that I was compelled to compose so many pieces in its reflection. I’ve written nine or ten works for voice(s), flute, clarinet, and viola – a ridiculous ensemble – as a kind of post-mortem epistolary conversation with Stravinsky. Most of my music I think of as letters to dead composers, fan letters, in which my compositions are questions or – when I feel so bold – answers to the masters I revere. I’ve written eight “books” of music set, mostly, to Shakespeare texts, which I call the Oxford Songs. Most of the twelve stories in Book VI are scored for voice, flute, clarinet, and viola. They are all messages to Stravinsky, stories of my admiration and love for his music, and my attempt to ask him – through music – his opinions. On this recording appear “I do not know one of my sex,” “O Mistress mine,” and “Love, what thing is love,” three selections from Book VI. Oh, I forgot, and “Before you can say come and go,” which is a fifteen second setting of a breathless Ariel, appealing to Prospero for approval. So, make that four stories from Book VI. My setting of “Full Fathom Five” is not from this book, but is the twelfth chapter of Oxford Songs Book III.

Stravinsky’s Three Songs from William Shakespeare begin with Sonnet 8, “Music to Hear” and conclude with a ribald song from Love’s Labour’s Lost, “When daisies pied.” Between the two is “Full Fadom Five.” Stravinsky had an odd relation with text. He is often criticized for his static and syllabic settings, especially of Latin and English. The three settings of Three Songs from William Shakespeare may seem distant from the meaning of the words, but upon repeated listening I find the music very descriptive, not as abstract as some critics have maintained. That might just be me. When I cobble together a disc like this one, in which several different composers interpret the same text or idea, I am imitating Akira Kurosawa’s 1950 film, 羅生門, Rashōmon, based on Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s “In the Wood.” The film explores the idea of alternative interpretations. In Rashōmon, a single story is retold several times by four different characters, based on their individual perspective on the same incident. When I first saw the film, sometime in the late sixties at the FORVM Theater on Forbes Avenue in Pittsburgh – I never pronounced it “forum” because of the wonderfully Latin rendering of the “U” that adorned the theater’s façade – I was immensely intrigued by the film’s conceit. In this recording, we are able to hear The Tempest from the very different perspective of six very different composers. As we do, we can hear their reflection on that sinking ship, on sojourners transformed from men to coral.

In February 1956, Charles Ives’ “A Sea Dirge,” was premiered at Yale University. “A Sea Dirge,” is the text from “Full Fathom Five,” from the Shakespeare, though Ives referred to it originally as “Full Fathoms Five.” Perhaps our Ives’ enthusiasts have chosen to focus on the “A Sea Dirge” as the title so as not to have to think about the mistaken pluralization Ives used; though in the sketch, Ives writes “fathom” clearly.

Fathom, from the Old English fæþm; it means to embrace, with outstretched arms. A man’s outstretched arms encompass six feet. It evolved from an embrace to indicate the length of the embrace (six feet) and then it found a home in the sea, as a measurement of depth. From the literal meaning of depth it grew to mean depth of thought as well.

Though but a boy at the time I wrote some of the music on this disc, I was already greatly enamoured of a young woman, a fellow French hornist, Lisa Sclarsky. In 1970, at 14 years of age, I was sitting in the orchestra room of Taylor Allderdice High School, assistant second hornist with the Pittsburgh Public Schools All City Orchestra, when I espied a girl approaching me, with a horn case. When first her eye I eyed, I fell madly in love with her. She took the chair next to me, principal second horn. I was to obey her. She, two years my senior, held me in low esteem, except as a musician. My love would be unrequited, for too too long.

After our fortuitous meeting at All City, Lisa and I made beautiful music together, playing in orchestra, as well as attending the Centers for The Musically Talented on Saturdays, and even getting together to play duets in each other’s homes. In 1972, Lisa was already in college, but she told me she was planning to attend the Eastern Music Festival, which I had attended the previous two summers. I told her that I was going for one last time, and I was thrilled at the prospect of sitting next to her every day, at EMF. No longer a callow youth of 14, but now 16, on the edge of manhood, my feet already placed on the promising pasture of undergraduate school, I thought I could try to gain Lisa’s affection. We had to audition for our placement in one of the two student orchestras, and as fortune once more favored me, I was named assistant principal to Lisa’s principal first horn. I was to do her bidding for six weeks of midsummer music making. Before rehearsals we would dine together, and afterwards we would wander the campus and talk, speak of our plans for our futures. She told me about a cyst she had beneath her ear, and how she was worried it would impair her hearing. I told her jokes about parrots, pachyderms and pecans. Through her limpid tears of fear, she laughed at my attempts to assuage her concerns about the upcoming aspiration. I had brought her joy. She mesmerized me. I knew we were perfect for each other. I built up my courage, and told her that I loved her. She replied, “That’s not what I meant you to feel.”

Leaving EMF, my dreams of love dashed on the jagged rocks of reality, I went home to Pittsburgh and packed my bags for a trip to Mexico, taking my younger brother with me, to scuba dive and drown my sorrows.(6) Upon arrival on the island of Cozumel, a few years before the presence of hotels or college coeds or even Spanish speaking people – nearly everyone on the island was of Mayan descent and spoke Tzotzil, and had a very negative opinion of ‘Mexicans’ – I found us accommodation in a trailer home motel, owned by the mayor of Cozumel. I rented a pair of motorcycles so we could ride out to Laguna Chancunab, where there was, reportedly, great scuba diving. My mother’s boyfriend, Maynard Duncan, a former Navy navigator, my favorite and best “father," a barrel chested tenor who had sung in the chorus of the Metropolitan Opera Company (and who would eventually turn my compositional direction to opera and the voice) had given me his US Navy scuba diving manual, which I read attentively on the flights down. Arriving at Laguna Chancunab on our choppers, we were both eager to go scuba diving for the first time. (We had snorkeled for years, whenever my mother could scrape together enough money to go to Puerto Rico).

On the beach stood a rude wooden structure, attended by an American who I thought was in his sixties, but may have been much younger. It seemed he’d lived a hard life, and he was scarred and emaciated, though with a prominent belly. Clearly, he was in charge of what was Laguna Chancunab’s sole diving establishment. Mitchell and I had our dive masks and fins. We needed tanks. I approached the ancient sub-mariner and asked if I could rent some tanks. He looked at me, lethargically, and inquired, “Do you have a license?”

I said, “Yes.” He pointed to the rear of the shack and told me to help myself to tanks and weights. I pulled out two of everything, my brother apparently being “brothered” in to my nonexistent diving license. On a grey pier I set up the tanks, explaining to Mitchell what I was doing; the information which I had gleaned from the Navy manual. We had a tank, airhose, regulator. No Buoyancy Control Device (BCD), no wet suit, no console with depth information; nothing to clue us in to our air pressure. I strapped some weights onto belts, having no clear understanding as to how many pounds would be appropriate; and Mitchell and I jumped off the pier. To settle any doubts before I continue, this was really stupid. I had read the manual and knew many things, but what I didn’t know could have killed us. As it turned out, Mitchell, not understanding the concept of equalizing, injured his ears immediately, and had to return to the surface. He was done diving for the remainder of our trip. I, however, ignoring the admonition to never dive alone, dove alone. My weights were inadequate. Fortunately, before I adjusted them on my succeeding dives, the ocean floor had some nice heavy rocks, so I found one very heavy stone and simply carried it in my left hand, enabling me to acquire a pleasant negative buoyancy. A short distance from the pier was a gigantic brain coral, a magnificent sphere, top to bottom almost certainly thirty feet. It hosted an entire ecosystem (not that I would have used or known that term then) of amazing sealife. Figuring the globe to be approximately five adult men deep, I considered it safe to dive to its bottom and use the brain coral as my depth gauge. Five men head to toe would be thirty feet, or one atmosphere, and I was not going to get the bends from diving at one atmosphere for as long as my tank held out; and as well, no embolisms, nasty bubbles in my blood, if I had to surface fairly quickly. This is what I thought, dear reader, not necessarily the truth. For two weeks I dove Laguna Chancunab, alone, not a single diver there other than myself. My brother would swim above me, dropping pebbles on my tank to express his annoyance at being unable to accompany me below. My family returned to Cozumel the next year, and I learned that that titanic brain coral had been dynamited to allow for larger ships to enter Laguna Chancunab. Its pieces were used to build a wall next to a snack shop. I never returned. It would have been too depressing to witness.

Laguna Chancunab and its resplendent brain coral were my introduction to the world of full fathom five. A fathom is six feet. Full fathom five would be thirty feet deep; coincidentally: one atmosphere, the boundary between the world of man and the world of Nemo (Nemo being Latin for “No man”). Shakespeare’s line of metamorphosis beneath the surface begins there, at full fathom five, where men are transformed, perforce, into creatures of the sea. Could Shakespeare have known the science of ambient air pressure, the doubling at five fathoms? No, though Guglielmo de Lorena had built a functional diving bell in 1535 (based on the design by Leonardo da Vinci), it wasn’t until the late seventeenth century that Abbe Jean de Hautefeuille first explained the hazards of breathing air underwater as being caused by the change in air pressure. Today we divers use meters in thinking about the changes in air pressure, but the principal boundaries of ten, eighteen, and thirty meters could easily be replaced with five, nine, and sixteen fathoms. My forays into depths beyond full fathom five began at Laguna Chancunab, when I unwisely decided to venture deeper than the brain coral. Since then I have descended below five fathoms innumerable times. I stopped counting my deep dives after a thousand. The young hornist who spurned me repeatedly for seven years, beginning in orchestra, eventually succumbed to my relentless begging, and in 1977 I took her to my family’s home in the Virgin Islands, introduced her to the warm Caribbean waters and the wonders beneath. A year later we married, sharing a love for music and the depths. Lisa and I are obsessed with diving. We live most happily beneath five fathoms, and we are transformed in the depths. In 2001 I wrote my treatment of “Full Fathom Five,” attempting to limn the spume through which we pass to the serenity of the deep in which we are metamorphosized; we undergo that sea-change spoken first by Shakespeare in The Tempest.

Lisa and Joseph Summer, full fathom five in the Lembeh Straits of Sulawesi, examining a flamboyant cuttlefishIn my second and third years at Oberlin conservatory I became Oberlin’s first composition/acoustics & technology double major. I dropped the double major before my senior year for a number of reasons, including the fast paced changes in the world of computers. During the course of less than three rotations around our sun, I had become a caveman, lugging boxes of IBM computer punch cards while the newcomers looked at me with pity. Before my departure from the field of technology I created several compositions using the techniques of Musique concrete. “Conversion” is included on the enhanced content of this disc. It is one of my experiments in transforming the sounds of acoustic instruments through sundry simple alterations. “Conversion” begins with the two instruments: French horn and viola. I played the horn and my colleague and best friend and roommate at Oberlin, William Henry Curry, played the viola. I recorded several passages I had written or we had improvised, on tape. Then, with scissors and scotch tape, I cut and paste audio tape into different orders and shapes. Subsequently, I mixed the sounds with a handful of rudimentary filters and reverberation units; altered the speed of playback, and created feedback loops of the playback. The title, “Conversion,” was meant to describe the concept of taking acoustical sounds of viola, horn, and voice; and transforming the material through a few crude manipulations of tape, playback loops, and filters; to create something that sounded removed from the original “input.” The viola and horn underwent a “sea-change,” if you’ll permit me the description. Hearing the piece – decades after I shaped it like Victor Frankenstein, in a basement music lab – I find that the altered sounds derived from the two instruments are still interesting, if only in that this “electronic” music of the early seventies sounds nothing like the sophisticated electronic music of the 21st century. Those who are familiar with “Poème électronique” by Edgard Varèse will recognize that I have used some of the exact techniques he pioneered; most apparently: filtered human voice, reverb and distortion.

Lisa and Joseph Summer, full fathom five in the Lembeh Straits of Sulawesi, examining a flamboyant cuttlefishIn my second and third years at Oberlin conservatory I became Oberlin’s first composition/acoustics & technology double major. I dropped the double major before my senior year for a number of reasons, including the fast paced changes in the world of computers. During the course of less than three rotations around our sun, I had become a caveman, lugging boxes of IBM computer punch cards while the newcomers looked at me with pity. Before my departure from the field of technology I created several compositions using the techniques of Musique concrete. “Conversion” is included on the enhanced content of this disc. It is one of my experiments in transforming the sounds of acoustic instruments through sundry simple alterations. “Conversion” begins with the two instruments: French horn and viola. I played the horn and my colleague and best friend and roommate at Oberlin, William Henry Curry, played the viola. I recorded several passages I had written or we had improvised, on tape. Then, with scissors and scotch tape, I cut and paste audio tape into different orders and shapes. Subsequently, I mixed the sounds with a handful of rudimentary filters and reverberation units; altered the speed of playback, and created feedback loops of the playback. The title, “Conversion,” was meant to describe the concept of taking acoustical sounds of viola, horn, and voice; and transforming the material through a few crude manipulations of tape, playback loops, and filters; to create something that sounded removed from the original “input.” The viola and horn underwent a “sea-change,” if you’ll permit me the description. Hearing the piece – decades after I shaped it like Victor Frankenstein, in a basement music lab – I find that the altered sounds derived from the two instruments are still interesting, if only in that this “electronic” music of the early seventies sounds nothing like the sophisticated electronic music of the 21st century. Those who are familiar with “Poème électronique” by Edgard Varèse will recognize that I have used some of the exact techniques he pioneered; most apparently: filtered human voice, reverb and distortion.

1) In the performance footnotes to my 1923 edition of the Beethoven piano sonatas, published by Schirmer; Dr Theodore Baker, describing Schindler’s testimony in regard Opus 111, writes, “Let this (“A Critical Catalogue of Beethoven’s Works” by Wilhelm Von Lenz) stand in confutation of Schindler’s mischievous and widely disseminated story that Beethoven dismissed his (Schindler’s) advice to compose an additional triumphant third movement with the not exactly sublime answer, that he had no time for it – he must keep at work on the ninth symphony. – Do not mistake us; we in no way doubt the authenticity of the Master’s reply. But consider to whom it was given; admire the angelic moderation that lies in this evasive triviality, when a pointed retort would have been far more relevant. One is almost tempted to congratulate the great composer on his dreadful affliction, in that it at least protected him against an immediate perception of all the disrespect and nonsense wherewith that blockhead was always intent upon molesting his great ‘friend.’” This edition of the sonatas, by the way, is sublime. The footnote on page one of Opus 111 occupies more than two thirds of the page. There are two systems of music, the opening five bars of music, and then four footnotes about the music, including a nearly four hundred word excoriation of Schindler, a portion of which, but a portion, I quote above. How glorious is it that an edition of the Beethoven piano sonatas could include a performance footnote labeling Schindler a “blockhead,” and using sneer quotes around the word friend, not to mention praising Beethoven’s deafness as an avenue of escape from the foolishness of his acquaintances? (click to go back)

2) As I write these liner notes I am contemplating omitting the Sheridan text from the hard-copy booklet, because I don’t think the listeners should be distracted from the lovely Linley music by the execrable poetry. (click to go back)

3) “Que sera, sera”is a line from The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus by Christopher Marlowe, and not only the popular song written by the Jay Livingston and Ray Evans (and sung famously by Doris Day.) Prior to Marlowe it appeared as a fatalistic heraldic motto in 16th century England. (click to go back)

4) The “Centers” as we humble students called The Centers for The Musically Talented, held classes in music theory and history, provided coaches for chamber ensembles and private lessons, all free, on Saturday afternoons. Friday after school (Taylor Allderdice High School, in Squirrel Hill), I’d either take the 67H bus (if it was snowing or raining) or walk (to save the bus fare) the two miles (through beautiful Schenley Park) to my grandparent’s home at 3505 Boulevard of the Allies (the best named street in Pittsburgh). I’d sleep over Friday night, my grandmother preparing a dinner of lamb and French fried potatoes for my younger brother (who would arrive separately from elementary school courtesy of our mother) and myself before turning off the electricity in favor of the Sabbath candles while my grandfather ranted in Russian and Yiddish about politics. Saturday morning I’d wake up and, with my painfully heavy horn case, walk a mile to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, stroll for an hour through the dinosaur exhibit (all of which have long since been remounted to reflect the revised postures of the fleet extinct creatures, as opposed to the lumbering sluggards I knew them as) and then to the Carnegie Music Hall, which, an hour after the museum opened, would host the Tam O’Shanter art class, free instruction for those recommended by their art instructors in public school. At the conclusion of the art class, I’d pick up my horn and walk west on Forbes Avenue, then a dogleg up to Fifth Avenue for less than a mile, to Fifth Avenue High School where the free music instruction took place. Mihail Stolarevsky had created the Centers for The Musically Talented to foster musical proficiency in students who might not otherwise be able to afford instruction. It had a reputation for producing some excellent young artists and developed a relationship with a couple recruiters from music conservatories. (click to go back)

5) It was a cheap paperback edition, bound in lime green papers, from Kalmus Publishers. Oh, those who might question a youngster’s ability to read Le Sacre, the score is not as complex as one would imagine. The most difficult element is the changing meters (but that’s always been an area in which I was comfortable). The viola harmonic passage begins at Rehearsal #11. (click to go back)

6) Of course, this was not a well-thought out plan, as apparently the authorities in the United States didn’t think it advisable to allow a 16 year old, traveling with his 13 year old brother, to leave the country on their own recognizance. Halfway through our trip, in the Miami airport, Mitchell and I were pulled aside prior to boarding our next flight. I was informed that I was a minor, and couldn’t take an even younger minor outside the country. Well, it was a surprise to me. I hadn’t considered this possibility, and neither had our mother who had permitted the two of us to embark on this quixotic adventure. Thinking quickly, I told our wardens that we were going to meet our mother once we arrived in Cozumel, that she was taking a later flight. This was a bald-faced lie. Our captors suspected as much, but agreed to call our mother, in Pittsburgh, at her work, which was the Child Welfare Offices at which she worked in the capacity as supervisor and case worker. My mother, Eunice, was quick on the draw, and upon hearing the voice on the other end of the phone ask whether, indeed, my story of meeting her in Mexico was true, she too lied and said that it was true and that if they stopped Mitchell and me from continuing our journey the results would be more than inconvenient, they would be disastrous. She used her employment as a child welfare worker to bolster her unsupportable position, and so we were free to continue our passage to Mexico. Mitchell’s crying was useful, too. (click to go back)