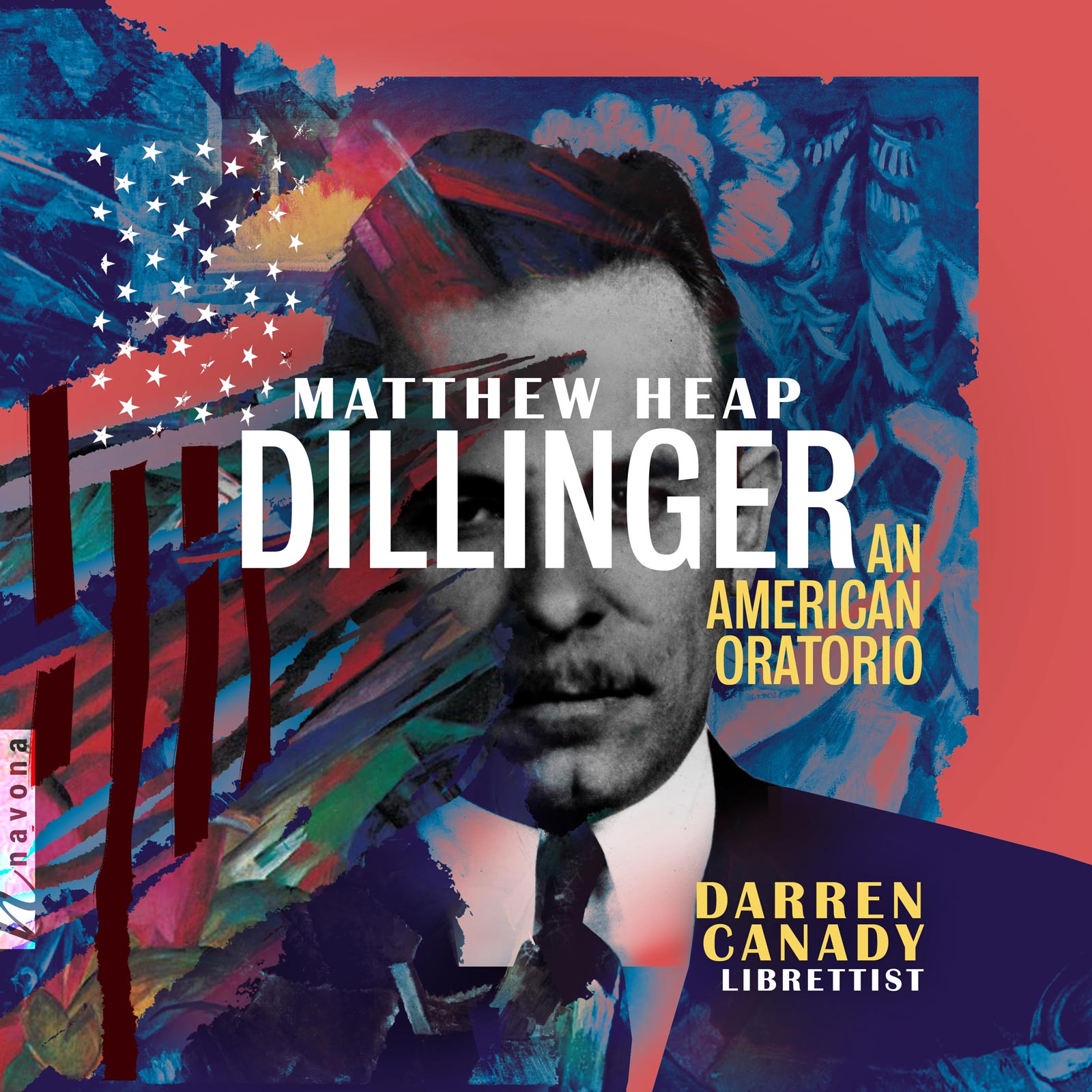

DILLINGER: AN AMERICAN ORATORIO from composer Matthew Heap in collaboration with librettist Darren Canady dramatizes the life of notorious Great Depression-era bank robber John Dillinger. Seen alternately as both an enemy of the state and a folk hero, Dillinger’s story is a fitting backdrop to Heap’s nuanced exploration of class warfare and the American Dream.

Today, Matthew is our featured artist in “The Inside Story,” a blog series exploring the inner-workings and personalities of our composers and performers. Read on to learn about the app he designed to help students learn music theory, and how his background in computer science influences many aspects of his daily life…

What were your first musical experiences?

I started playing the violin when I was really young — maybe 4 years old. I was taught using the Suzuki method (playing largely by ear and using repetition and imitation to learn). According to my mother, whenever we went to larger group lessons/performances and they asked someone to stand and repeat what they’d played, I would always be the first one to jump up. I’d then play it entirely wrong. After about a year of this, my teacher suggested that I go and learn piano to strengthen my fingers. Young me thought that piano was much easier to make a lot of noise on than the violin, and that stuck. My piano teacher was supportive with early attempts at composition — I’d add left-hand parts to right-hand only pieces — and encouraged me to try writing something on my own. This was reinforced in school (in the United Kingdom), where our music teacher had us writing our own little pieces at a very early age (including a mini 12-tone piece). When I got to middle school, I had the compositional confidence to write a little musical based on the Beatrix Potter book The Tailor of Gloucester, which the school put on. I kept going from there.

What advice would you give to your younger self if given the chance?

I’d definitely tell myself to make more connections in college with performers — so many amazing new music ensembles came from that kind of setting, and you never know who is going to be an advocate for your compositions. I’d also tell myself to really take every opportunity while you’re in that college setting. Finding performers and performance spaces becomes (almost) infinitely more difficult when you’re outside academia. I think “young Matt” took that for granted a little bit.

Take us on a walk through your musical library. What record gets the most plays? Are there any “deep cuts” that you particularly enjoy?

I have really eclectic tastes and I’ll listen to just about anything, but there are some things that I gravitate towards. In the classical world, there are the big exciting pieces like The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky and (probably my favorite) Sinfonia by Luciano Berio, but there are also really unique pieces like Part 3 of Arnold Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder. The whole piece is great, but it’s about 90 minutes long — the story is that he wrote the later part of it several years after the early part, and the influence of his experiments with breaking down the tonal system can be heard in what starts as a very late-Romantic piece. Plus, the ending is glorious. Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloe is amazing too. I also listen to a lot of musical theater (and there are definitely influences from that in my concert music). Anything by Sondheim, but particularly Sweeney Todd), Hamilton, Hadestown, Avenue Q, and Urinetown are pieces that I come back to a lot. They all treat the musical theater tradition in a slightly different way that respects it by pushing the boundaries. That’s a small subsection of the music I come back to repeatedly, but those are all important works to my development.

What emotions do you hope listeners will experience after hearing your work?

That really depends on the piece. For DILLINGER: AN AMERICAN ORATORIO, I really want people to be swept along by the music. There’re really only three pauses in the entire piece (although there is one slower section). It should be a little overwhelming. I also want people to think about why John Dillinger was (along with a few other criminals) held up as a hero to the people. He certainly didn’t share his proceeds. Those people saw the rich get richer at the expense of the poor, and they were excited to see someone take on the “fat cats and banking men.” The fury of the music at the end, coupled with the lyrics, hopefully creates some fire in people’s hearts to tackle some of these societal issues. Other pieces that I’ve written (I’m hoping) will transport people. The two-piano piece And the Earth Sang to Me Through the Wind is supposed to take you to a precipice with an amazing view and the wind whistling around you. There’s also a sense of whimsy to a lot of my pieces — a tongue-in-cheek playfulness with musical ideas.

What’s the greatest performance you’ve ever seen, and what made it special?

I’ve had the fortune to have gone to a lot of amazing performances over the years, but one stands out as an event rather than just a concert. The piece was Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, performed by the London Philharmonic Orchestra with Kurt Masur conducting. The piece is amazing and moving all by itself, but what made this extra special was that it was on June 6th, 2004 — 60 years after the D-Day landings. The crowd was filled with veterans and their families and there wasn’t a single person who wasn’t crying during the performance, especially during the “let us sleep now” sections that close the piece (I just got chills thinking about it!). The orchestra was clearly feeling it too and gave a stunning performance. It was just one of those times that the right piece was played by the right people for the right audience at the right time — a magical concurrence.

If you weren’t a musician, what would you be doing?

When I was applying for undergrad, I was torn between doing a music degree and a computer science degree (I feel like composition works the same parts of the brain as programming in some regards). I was supposed to do a double major, but I ended up focusing solely on composition, and I’ve always been pretty sure that was the right (although probably less lucrative) decision. Computer science still has a place in my heart, whether it’s programming in electronic music software like Max/MSP or making an app to help students learn about music theory (Theory Game: Curse of the Lost Rules — free on the App Store and Google Play!).

There’s something about the logical train of commands that really works for some part of my brain, and part of my composition teaching method has to do with helping students find the musical logic behind the choices that they make. So, even though I don’t use computer science every day, it’s still a driving force behind a lot of the things I do.

Matthew Heap, born in 1981, is an internationally-performed composer whose music has been featured in several American and English cities and on WQED and WCLV radio. He is also very involved in the theater community as an actor, director, and writer. Matthew received his B.F.A. from Carnegie Mellon University, M.M. from the Royal College of Music in London, and Ph.D. from the University of Pittsburgh. He has studied with Leonardo Balada, Eric Moe, Nancy Galbraith, Mathew Rosenblum, Amy Williams, and Timothy Salter.