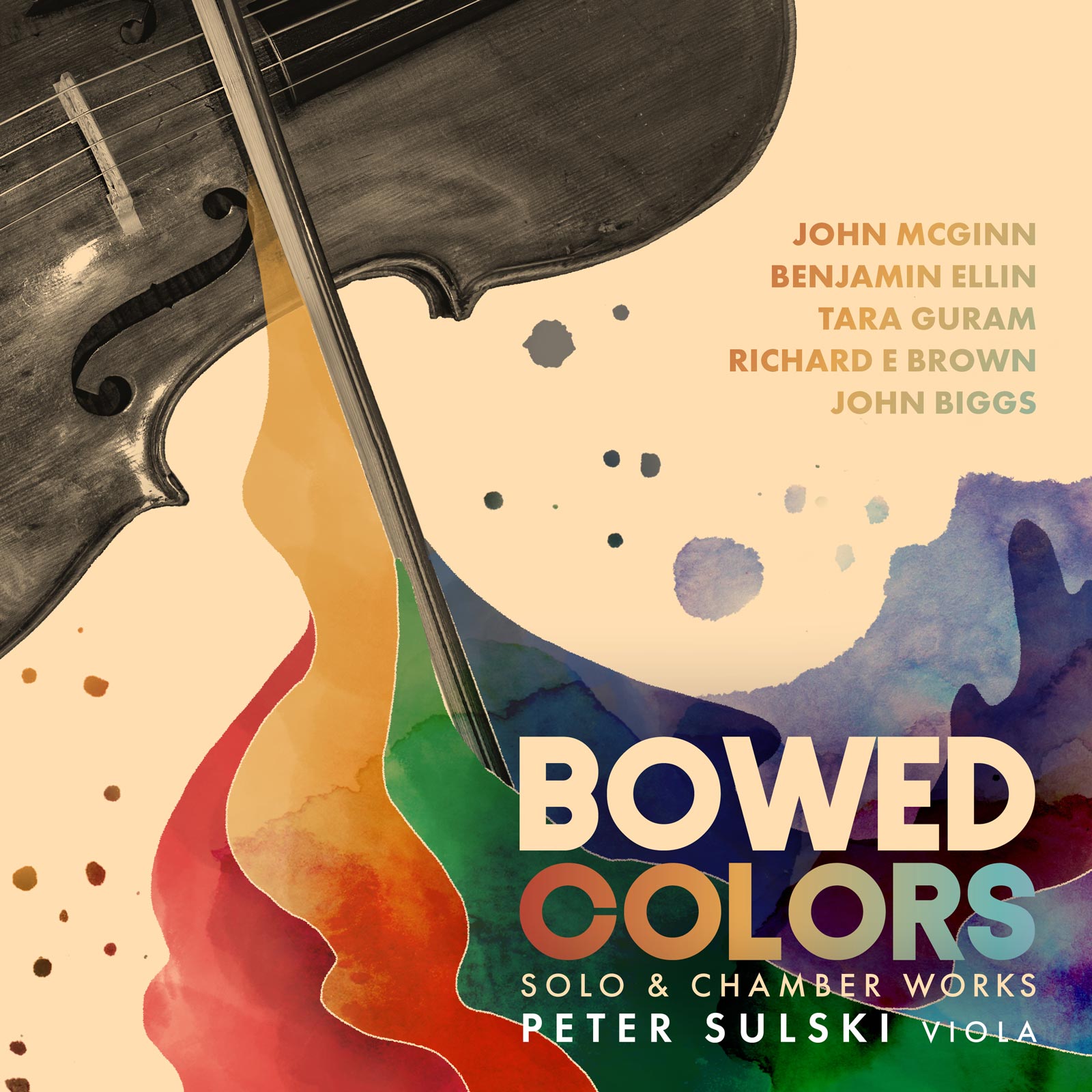

Combining violist Peter Sulski’s signature sound with the works of five composers, BOWED COLORS delivers an exquisite selection of contemporary solo viola pieces that range from the neoclassical to the just barely tonal, all tightly knit together by Sulski’s sublime bow control and finesse as a performer. Featured on the album is composer John McGinn and his piece, Capriciously Strung, a piece highlighting different shades of the viola’s potential for quirky playfulness, as well as its gritty power and quietly eloquent expressiveness.

Today, John is our featured artist in “The Inside Story,” a blog series exploring the inner workings and personalities of our composers and performers. Read on to learn how a release of frustration gave way to a compositional enlightenment for John, and how that very moment unlocked a new passion for free improvisation…

When did you realize that you wanted to be an artist?

Just shy of my 7th birthday, my parents purchased our first family instrument, a tall black upright player piano with its mechanism removed, for $100. My older sister started group piano lessons; jealous, I begged for the same. Her interest soon faded but I was perfectly hooked. About a year later, on a whim, my mother purchased a small packet of manuscript paper. I clearly recall filling up two full pages willy-nilly with notes which she lovingly played for me (in truth it sounded like nothing, but I didn’t mind). I then jotted down something more coherent: a two-bar melody swiped from a cartoon. But then the next two bars were my own, and a few more after that. Later that day, I announced to my best friend Scott that I was going to “be a composer.” From then until now, that tune hasn’t changed.

Who were your first favorite artists growing up?

Perhaps just weeks later, my mother obtained the 1967 reissue of the LP and booklet Walt Disney Presents The Great Composers. I fell head over heels for the very first notes that sounded (by Bach) and then every note after that, and every story. When I was nine, I ripped open Christmas wrappings to find the Dover score of Beethoven’s Complete String Quartets along with LPs of the five middle quartets (Guarneri); most other toys lay neglected for weeks. Soon enough, my piano teacher Elinor Armer lent me a score and recording of Mozart’s Symphony No. 35, the first orchestral score I’d ever held … and that, as they say, was that. Studying composition with John Adams (then a relative unknown) at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, I devoured classical scores from the library and went through phase after phase in my own works: “not quite” Bizet, “not quite” Debussy, “not quite” Bartok, “not quite” Keith Jarrett (one of my father’s favorites) and so on. I feasted musically as a composition student at summer workshops in my native California, the Walden School in Vermont and the BUTI Tanglewood Institute, then on to Harvard and beyond. Only years later, revisiting my youthful works in order to enter them into software, did I come to realize that all of those “not quites” had actually added up, pointing unmistakably towards a voice that was uniquely my own.

What was your most unusual performance?

Not a performance but a composing session, within a small cabin situated in the bucolic woods of the Berkshire Mountains in Massachusetts during my summer as a Composing Fellow at the Tanglewood Music Center in 1985. This particular afternoon in mid-July, I found myself approaching something akin to desperation. All attempts to further my “supposed to be brilliant” piano trio (written under the tutelage of Leon Kirchner) were proving fruitless. What was wrong with me? How could composing, always so simple and fun in the past, have suddenly become so difficult? I still remember clearly the moment, following erasure of yet another “worthless” measure, when my hands raised up high and came crashing down upon the keys! Some undefined cathartic need being met, my hands continued to hammer loudly and chaotically upon the keys for several minutes, up and down, all around; presumably, my little sonic tantrum would eventually run out of steam and I’d resume my dogged strivings. Rather to my amazement, it didn’t. The hammering gradually receded in volume and intensity to be replaced by … something else, I had no idea what. And it just kept coming and coming, one wave after another: ideas, gestures, textures, interactions, climbs, falls. I haven’t a clue where it was coming from or what was holding it together, if anything. Nor did I attempt to guide it in any way, I simply let it flow forth – which it proceeded to do for nearly two hours. At long last, the sunlight began to fade outside, my fingers crept their way to some sort of final phrase and ceased. I sat there, heart racing. I was then struck by two singular realizations. First, much of what had just reached my ears was largely unfamiliar to me; it was unlike any composition I had ever heard, either by myself or by anyone else. Second, a surprising amount of it had actually sounded – and felt – genuinely good. Indeed, perhaps as good or better than anything I had ever actively, consciously composed. Unbidden and unexpected, a tantalizing new musical door had opened to me.

Is there a specific feeling that you would like communicated to audiences in this work?

It has now been nearly four decades since that astonishing afternoon in the Berkshire woods, and alongside plenty of composing and performing in the traditional sense, my fascination with and pursuit of free improvisation has been fervent and ongoing. Technology has of course proved a great boon, with cassette tapes and pencil giving way in the 1990s to MIDI software, allowing me to capture, transcribe, and ponder my spontaneous musical outpourings. Indeed, one of the most compelling questions for me has been whether it’s possible to truly merge the unbridled winds of free improvisation with the intricate craft and technique of conscious composition. In recent years, I’ve made some highly promising strides in this regard, basing numerous fully notated compositions on MIDI-transcribed passages of improvisation, including Without a Net (2008, revised 2020) and two sets of solo piano Preludes (2015 and 2019). In such pieces, I’ve responded to transcriptions just as I would to any compositional materials – analyzing, developing, connecting with other passages (perhaps also improvised), honing transitions and so on – with the goal that listeners will experience something that feels at once spontaneous and carefully structured. Of special note for this album, Capriciously Strung (2008), while otherwise meticulously composed, is the very first work in which I dared to include such a passage. (No hints – though I welcome listeners to have fun trying to guess where!) Beyond this, the title does reflect a certain “flights of fancy” quality within the piece, perhaps due to the sheer variety of distinctive gestures, moods, texture and interactions – so much is possible with just a viola and piano! I recall a letter Mozart wrote to his father Leopold in which he speaks of striving for “il filo” (the thread), an almost mystical yet unmistakable sense of unity that may be spun through even the most contrasting of ideas. My own strivings in this regard in Capriciously Strung were a source of much creative fascination and delight for me.

If you could make a living at any job in the world, what would that job be?

As an undergraduate, I was asked more than once, why in the world would I think of pursuing music as a career? My answer was simple: I can’t imagine being happy for entire decades doing anything else. Somehow, via a combination of luck, copious effort and sheer doggedness, I’ve managed to make it so. Certain moments have been key, such as when, at the age of 23 (after mostly doing clerical temping to make ends meet), I received a panicked call from John Adams that the orchestra for a preview performance of his just-completed opera Nixon in China had fallen through, and could I please come to San Francisco on four days’ notice, learn the entire piano-vocal score, get a feel for the mighty Yamaha HX-1 Electone synthesizer, and hammer it out along with two grand pianos? Um … okay! I of course had a blast, and this led to further Nixon performances in Houston, Brooklyn (including the Grammy-winning recording), Washington DC (where I was living), Amsterdam and Edinburgh – very exciting! Succeeding years saw branching out to playing for musicals and ballets with the Kennedy Center Orchestra, as well as contemporary ensembles such as American Camerata (first gig: Elliott Carter’s Triple Duo and three other works on six days’ notice after the pianist bailed) and Earplay. I did a few turns creating piano-vocal scores of large-scale Adams works (The Death of Klinghoffer, Violin Concerto and others) for publication by Boosey & Hawkes. At various points, I’ve received offers to become an editor at a major record label and to become chef de chant (head accompanist) at a top European opera house; for personal reasons I had to turn these down but who knows where each might have led. As it is, at the age of 29, I had an epiphany that becoming a university professor would allow me to make a decent living while doing everything that love: teaching (which I sensed and then quickly confirmed a deep passion for as a graduate teaching assistant at Stanford), scholarship (in my case, composing, performing, directing) and service (letting me make satisfying contributions to institutions and communities). In this, I was absolutely correct. It has been such a vibrant, productive, joyous, enriching journey over the past two decades, teaching first at Clark University (where I met Peter Sulski and he asked me to write the piece on this album!) and, since 2008, at Austin College in Sherman TX. I consider myself blessed beyond words in the path my life and career have taken.

What does this album mean to you personally?

It means that there are people out there who are willing, able, and inspired to create superb albums like this and share them with the world! What a joy to have Peter and Randall pour such devotion, talent and heart into my Capriciously Strung and into all of BOWED COLORS. How heartening for Brandon MacNeil and Bob Lord to place such faith in my music. What a pleasure to work with so many stellar artists and professionals on the production (Brad, Levi), recording (Tom), editing (Melanie, Lucas), design (Ryan, Edward), publicity (Brett, Patrick) and other teams at PARMA. Perhaps most meaningful of all is the generous support of my dear friend Roger Sanders, who made possible my participation in this album, thereby allowing me to share this very meaningful work with anyone who may be moved or delighted by it. To all of you, I am immensely grateful!

An Associate Professor of Music at Austin College in Sherman TX, composer/pianist John McGinn received an undergraduate music degree from Harvard University in 1986 and his D.M.A. in Composition from Stanford University in 1999. Among his mentors are such noted composers as Jonathan Harvey, Leon Kirchner, and John Adams. His own works have received several honors and been performed at colleges and festivals worldwide.