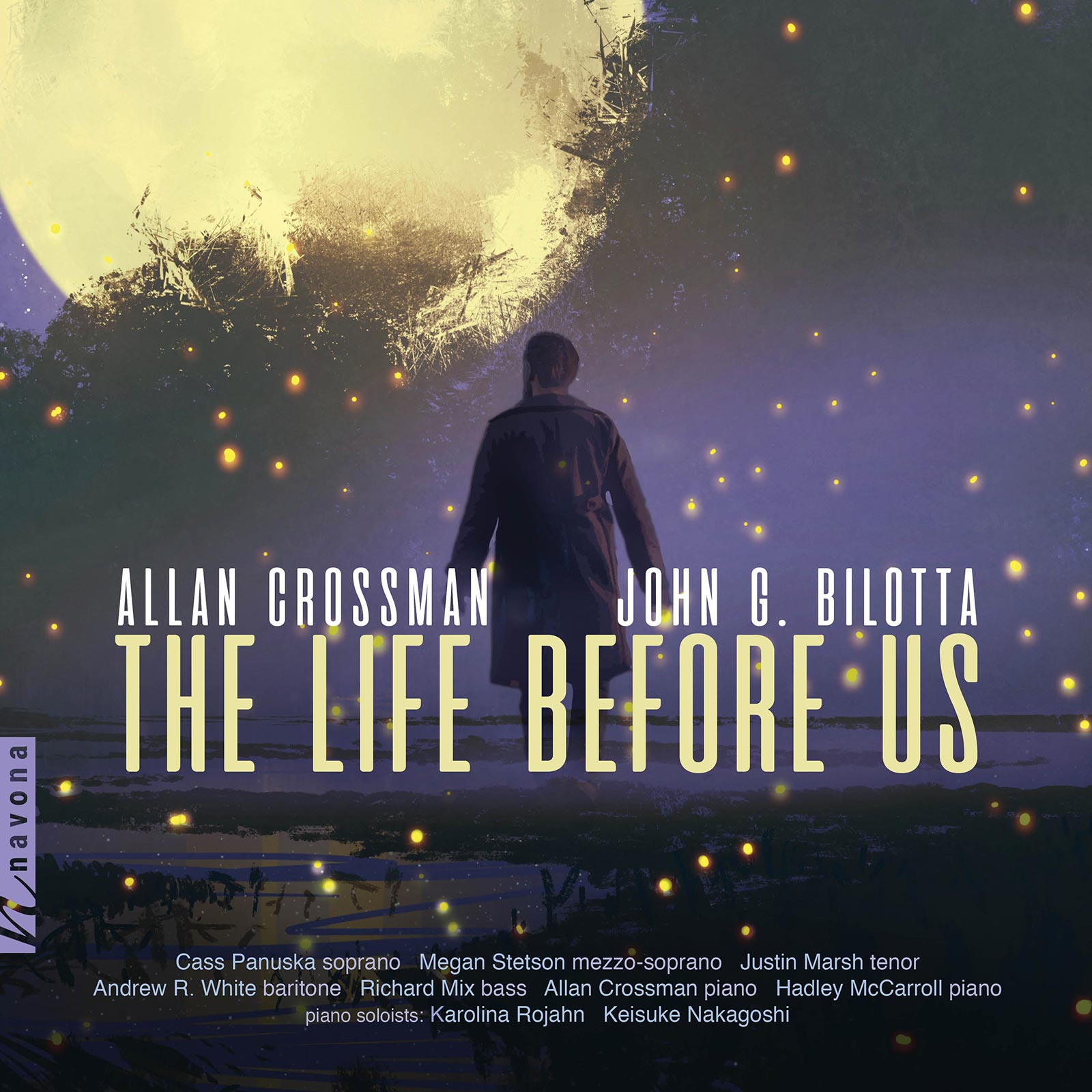

Bearing musical witness to the versatile talents of two acclaimed northern California-based composers, THE LIFE BEFORE US combines works from John G. Bilotta and Allan Crossman.

Today, John is our next featured artist in “The Inside Story,” a blog series exploring the inner workings and personalities of our artists. Read on to hear about John’s love of meatballs…with raisins…

When did you realize that you wanted to be a composer?

It was my childhood goal to be an astronomer. I didn’t surrender that ambition until many years later at Berkeley. Then suddenly, at the age of 12, I wanted to compose.

I had took music lessons during elementary school and sang in the Ridgewood Boys Choir but I was indifferent to the music we studied, all carefully prepared for young minds. My first year of middle school, we were asked to sit quietly, close our eyes, and listen to a recording of Sibelius’ Swan of Tuonela. I had never heard anything so haunting and decided to try writing something myself. Now that I knew where they were hiding the good music, I locked myself in the library listening to one incredible recording after another, studying scores, and reading on music theory.

Within a year, I had written a sonata for four pianos. The middle school music teacher asked to see it and set up a performance of the piece in front of the entire class assisted by three of her piano students. I was hooked.

What is your guilty pleasure?

I really miss my grandmother’s meatballs with raisins. Most people are surprised by the idea of raisins in meatballs but it was an old country recipe and I loved it. It wasn’t until I was an adult, long after my grandmother had passed away, that I found out from my cousins how much they hated meatballs with raisins. They complained that whenever we ate at my grandmother’s, she would be in the kitchen mixing raisins into ground meat and bread crumbs. But I was the oldest son of the oldest son of the oldest son in an Italian immigrant family and I was golden—maybe that’s really my guilty pleasure.

If you could do any job in the world and make a living at it, what would that be?

Composing, knowing full well that no one makes a living just composing anymore. Almost every composer I know earns his or her bread by doing something else—teaching, performing, administration, or working in a non-musical profession.

I have had opportunities to chat with a few distinguished American composers and when I asked one whether they were working on a new orchestral piece, their answer was “not without a signed contract and an advance.” So, whether making a living or not making a living, either you compose because you can’t not do it, or it fades into your past.

What would you say to an artist performing your work that nobody else knows?

Play it with expression, with freedom, let it flow. Pay attention to the shifting dynamics, the rhythmic modulations, and performance techniques specified, don’t gloss over them. Find the melodic ideas and let them sing. Find the harmonic ideas, however strange or unaccustomed, and let them be heard.

Some performers seem intimidated by contemporary music performance which I blame on the 20th Century’s reaction against 19th Century performance practices. The result is too often a performance that is rigid, mechanical, unbalanced, unwilling or unable to seek out and communicate the musical ideas. I once heard a pianist perform the first of the Three Sonatinas on this album in concert and I was stunned at how beautifully she communicated every aspect of the short work. Afterward, I asked her how she had prepared the piece and her answer was “The same way I prepare Schumann.”

Was there a piece on your album that you found more difficult to compose than the others?

The Hippocampus’ Monologue from the opera Rosetta’s Stone (on the subject of Alzheimer’s) was challenging for both practical and artistic reasons. The libretto was not yet finished but the lyrics for this particular aria were sent to me hastily in the hopes of being able to perform just that much of the opera at an upcoming Alzheimer’s conference in Israel.

It is relatively rare for me to write the sections of a work out of order because it undermines, or at least challenges, my integration of musical ideas across the piece. As it turned out, however, doing so allowed me to make this aria the centerpost of the opera around which everything else takes shape and to which everything else relates. The aria has since proven popular with singers and I am very partial to it.

Is there a specific feeling you want listeners to tune into when hearing your work?

Some of my pieces are very accessible and others are more challenging but every piece I write approaches the challenge of communicating the beauty and unity of all things in its own way and with its own grammar. I subscribe to Michael Tippett’s statement: “The role of the artist is the creation of images of vigour for a decadent period, images of calm for one too violent, images of reconciliation for a world torn by divisions, and in an age of mediocrity and shattered dreams, images of abounding, generous, exuberant beauty.”

John G. Bilotta was born in Waterbury, Connecticut, but has spent most his life in the San Francisco Bay Area having attended the University of California at Berkeley and, later, the San Francisco Music and Arts Institute where he studied composition with Frederick Saunders.