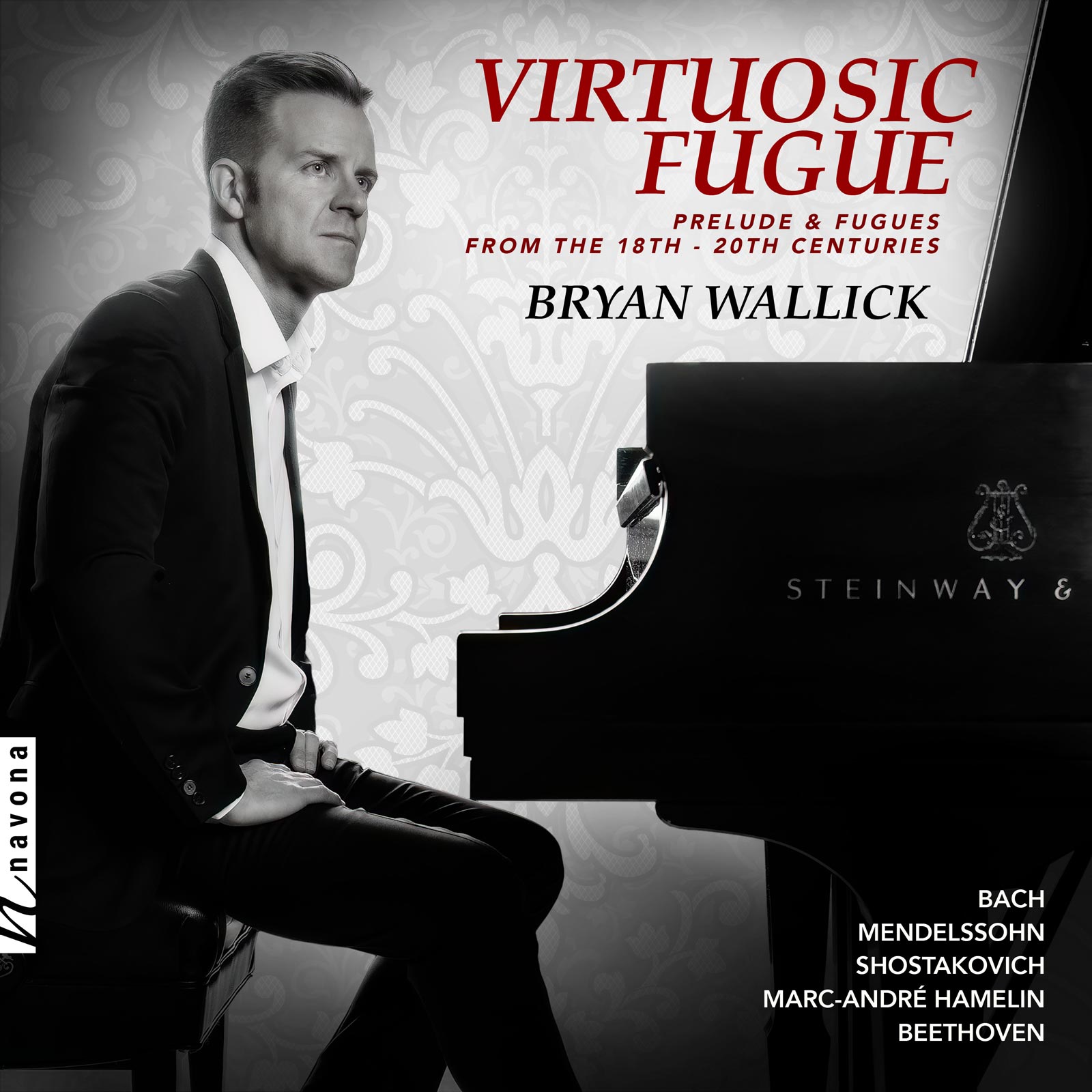

Good pianists are a dime a dozen, great pianists are one in a million. American virtuoso Bryan Wallick proves that he firmly belongs to the latter category on VIRTUOSIC FUGUE, a dazzling curation of music’s strictest and most challenging form, executed with a buttery, singing tone and ravishing technical bravura.

Today, Bryan is our featured artist in “The Inside Story,” a blog series exploring the inner workings and personalities of our composers and performers. Read on for an in-depth look at his practice regimen, musical library, and more…

What were your first musical experiences?

My parents were both musicians, so I had many experiences listening to them practice and perform which I would not even consciously remember before I started playing the piano at age 4. A few notable memories from my childhood include when I started playing Christmas carols by ear when I was 4, with some bass harmony, which led my parents to find a Suzuki piano teacher who began my formal studies. I went to numerous Handel’s Messiah rehearsals, which my parents performed in each December, and these experiences started my fascination with orchestral repertoire. I watched Vladimir Horowitz give his famous Moscow return recital in 1986 which made a huge inspirational impression on me when I was about 8. This inspired me to listen to many of his recordings and I decided by about age 13 that I wanted to be a concert pianist. At this time I also began studying with Eugene and Elisabeth Pridonoff at the University of Cincinnati (CCM) and they prepared me to go to The Juilliard School 1996 for my Bachelor’s degree.

How do you prepare for a performance?

I have a number of techniques and ways to practice before I feel comfortable performing in public. My doctoral dissertation studied the different ways concert pianists practice, so I continually feel like I’m trying to find the optimum way to practice which yields the best result with the least amount of time spent. I really like to feel comfortable understanding where both left and right hands play, meaning that I do a lot of practice where I just focus on the left hand (while still playing the right hand from “auto-pilot”) and then reverse where I just watch and listen to the right hand while the left hand plays on “auto-pilot.” I find this incredibly helpful with memory problems, and when I can control this exercise comfortably, I know I’m near performance ready. I also like to record myself as this recorder is the best “teacher” all artists can have after we finish school, when we do not have any more weekly lessons with professors. Once a piece is ready, or even after I’ve even performed it many times, I usually alternate between “practice” days where I will drill sections with rhythms or metronome, also using RH and LH focus techniques, and then I’ll do “play-through” days where I will just “practice” performing, taking chances, changing phrases, experimenting with different tempi, all in order to make a performance as “free” and improvisatory as possible.

What advice would you give to your younger self if given the chance?

I think I would give my younger self more encouragement to play chamber music earlier in my career. I grew up with more of a “solo” pianist mentality, I played some chamber music, but focused primarily on solo repertoire and concertos. I really only got more involved in chamber music when I finished my schooling and had the opportunity to perform with some wonderful violinists and cellists who were touring South Africa (where I was living at the time). I learned so much about music by working with other fantastic musicians, sharing ideas, finding inspiration on stage together, and these experiences are wonderful opportunities to infuse “solo” piano playing with more integrated musical forces. I believe that great piano playing is mostly about allowing the piano NOT to sound like a piano, but rather a string quartet, a soprano, a symphony orchestra, most anything that doesn’t resemble the percussive instrument it is. These outside musical forces and influences are also what helps pianists dig into our own scores and become really creative about how we want to express musical ideas.

Take us on a walk through your musical library. What record gets the most plays? Are there any “deep cuts” that you particularly enjoy?

As I look at my musical library (which is basically all virtual now..) I was originally inspired by artists who were serious virtuosos, pianists like Horowitz, Argerich, Richter, Marc-André Hamelin, etc… This type of virtuoso playing is what originally inspired my musical journey, and I still often gravitate toward this virtuoso-type repertoire. However, I have always admired Andras Schiff’s artistry, someone who is not really in the “virtuoso” camp, and my experience of his performances in New York and London, along with listening to many of his recordings and masterclasses have also made a tremendous impact on my artistry. I have always loved Bach’s music, and Schiff is the foremost pianist of our day to perform this repertoire, and even this new recording has a lot to do with his inspiration. VIRTUOSIC FUGUE shows a mix of both these influences; the Bachian world of Prelude and Fugues alongside the virtuoso repertoire it inspired like Beethoven’s Hammerklavier and Marc-André Hamelin’s Prelude and Fugue. These are the “deep cuts,” which mostly inspired my own artistic approach, but nowadays I usually listen to orchestral works, jazz, and mostly anything outside of the piano world. I listen to a lot of piano music as part of my work, but my mind is always judging, critiquing, correcting, inquiring about future repertoire, and it’s therapeutic to just listen to music I will never need or want to perform.

How have your influences changed as you grow as a musician?

As I’ve said above, my influences have changed mostly by widening the scope of my musical experiences and inspirations, moving from listening to mostly piano music and pianists, to listening to chamber and orchestral music. As most pianists study our instrument from early ages, our primary influences are our teachers, and I was lucky enough to have some wonderful teachers who pushed me to think “outside” the piano world, and these influences changed my artistry for the best. Since piano music is very often imitating other types of instruments, voices, and expressions, it forces a pianist to think about each and every note within a phrase, about what’s behind the musical intention this is plainly printed on the page, and about the world behind the music where life gets the most interesting as a pianist. This is where we make our own statements and expressions which allow us to say something different than the dozens if not hundreds of other pianists who have previously recorded and performed the standard repertoire.

What are your other passions besides music?

I believe it is very important for all artists and musicians to explore the history and literature of the great figures who have influenced our musical and artistic world. Since we live at least 300 years removed from Bach’s life and 18th century music, one can often find a big cultural disconnect from our 21st century life as compared to the lives of the mostly 18th-20th century European composers. Composers lived and reacted to personal, emotional, and political events, and even though we may not be aware of these connections when we first hear these works, the more we study and understand how everything in life connected and infused their musical experiences with their daily experiences, the “older” composers from foreign cultures seem not so unrelated to our lives and our experiences. We don’t have the social structures that Bach, Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven had to deal with in order to make their art, and understanding their struggle and relationship with these historical elements can unlock certain ideas and give more meaning to how we portray the emotional expressions in these works. The same is true of new music from modern composers; we don’t make music in a vacuum, and the more we can understand about their history and influences, the more meaning we can impart to our performances.

Bryan Wallick is gaining recognition as one of the great American virtuoso pianists of his generation. Gold medalist of the 1997 Vladimir Horowitz International Piano Competition in Kiev, he has performed throughout the United States, Europe, and Africa. Wallick made his New York recital debut in 1998 at Carnegie’s Weill Recital Hall and made his Wigmore Hall recital debut in London in 2003. He has also performed at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall with the London Sinfonietta and at the St. Martin-in-the-Fields Church with the London Soloist’s Chamber Orchestra.