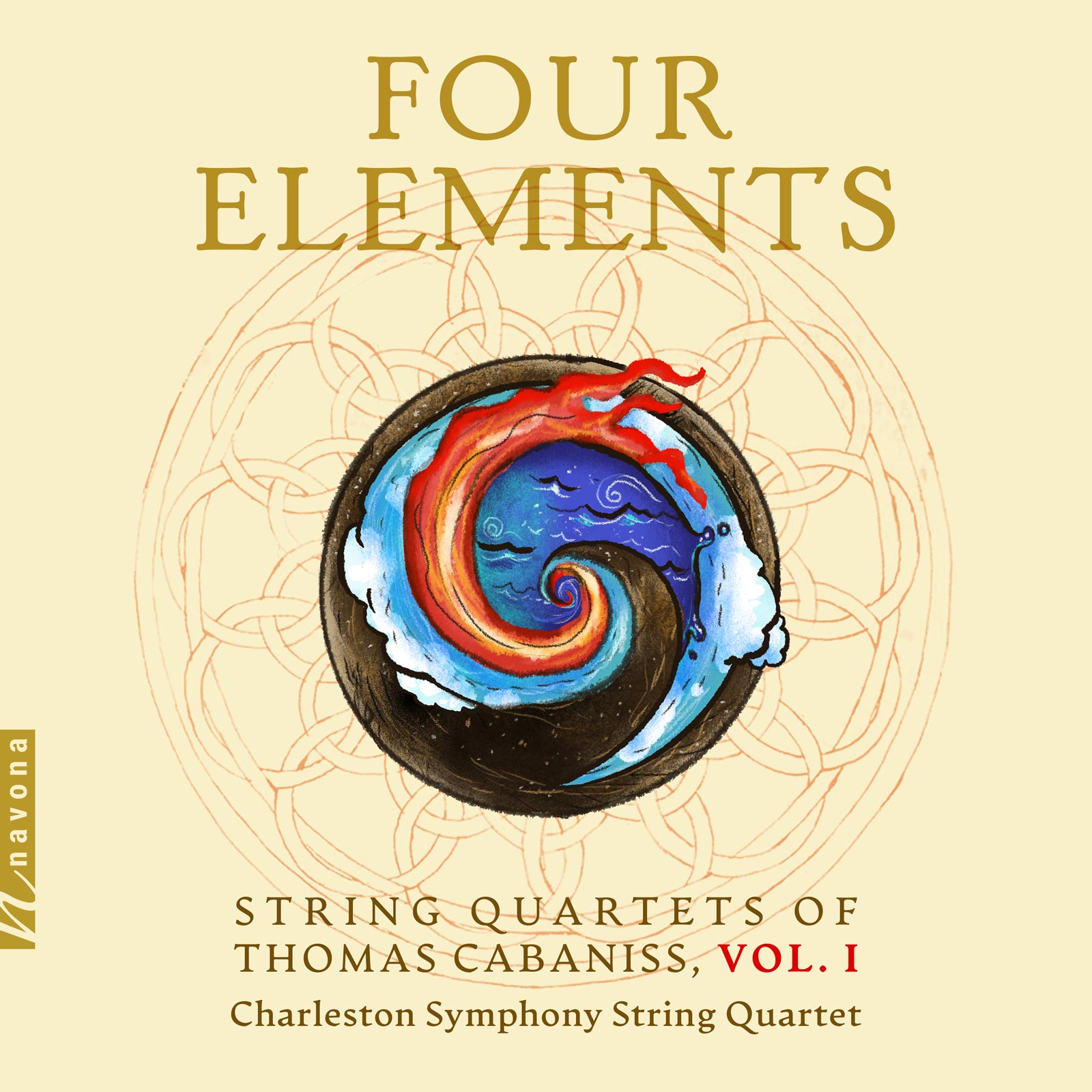

FOUR ELEMENTS from Thomas Cabaniss showcases the composer’s creative versatility developed over three decades collaborating across various artistic disciplines. Writing music for dance, theater, film, and the concert stage, Cabaniss incorporates elements from all of these forms in his works for string quartet. Performed by the Charleston Symphony String Quartet, FOUR ELEMENTS presents Cabaniss’s String Quartets 1, 2, & 5 — representing the first half of his output in this musical form.

Today, Thomas is our featured artist in the “Inside Story,” a blog series exploring the inner workings and personalities of our composers and performers. Read on to learn about the musical role that sparked his artistic journey and his passion for cooking South Carolina cuisine…

What emotions do you hope listeners will experience after hearing your work?

String quartets can hold some of the most intensely personal statements a composer can make — at least it’s seemed that way to me. They can contain singular soaring melodies and a constant community of relationships at the same time. So I hope that listeners will feel something of what I felt when creating them — a spectrum of emotions ranging from lyrical sadness to bubbling joy to in-between moments of meditation and wonder. As I was beginning to compose my first string quartet, I attended an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art that featured the works of Paul Klee. It included a work from 1934 titled “Blossoming.” It reminded me that abstract art has the power to move and transform the perceiver. I think music, and string quartets in particular, can do that, too.

What were your first musical experiences?

I sang the part of Louis (Anna’s son) in a production of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s The King and I. I sang “I Whistle a Happy Tune,” (and whistled, too!) It was at the Garden Theater with the Charleston Opera Company in South Carolina, in 1974, and it was the first place I experienced the power of music to tell a story and conjure a world on stage. I was about 12 years old, and though I had never studied an instrument, I began piano lessons that year, and I was off and running!

What musical mentor had the greatest impact on your artistic journey? Is there any wisdom they’ve imparted onto you that still resonates today?

I have been lucky to have several mentors throughout my life, including two brief stints with my idol, Leonard Bernstein (I worked as a musical assistant on Candide and A Quiet Place in the early 1980s). Mel Marvin, the Broadway composer, listened to my first song and gave me invaluable encouragement; he is still my close friend and guiding light. But the musical mentor who probably had the greatest impact on my artistic journey was my music teacher in middle and high school. He’s the one that got me started. You can blame him. Bill Becknell was the person who cast me in The King & I, and he was the one who sat beside my piano and helped me learn how to notate the songs I was writing by ear. To bribe him to stay longer into the afternoon, my mother would ply him with scotch. When I complained one day that I thought the music of Bach was too formal, too frilly, too ornamented to have deep emotion, Bill said, “One day you will grow to love Bach, probably around the same time you learn to drink scotch.” He was right.

Take us on a walk through your musical library. What record gets the most plays? Are there any “deep cuts” that you particularly enjoy?

There are many recordings of Janacek operas, including Osud and From The House Of The Dead, balanced by equal portions of South African pop (Soweto-beat, mostly) and anything recorded by Duke Ellington. Because of my work as education director at the New York Philharmonic in the late 90s and early 2000s, I have lots of recordings pulled from the Archives, and I own all the Young People’s Concerts on DVD — remember those? But I am obsessed with Keith Jarrett’s recordings of the Handel suites. They are literally on repeat in my kitchen and they are with me through every meal I create where there is time and space to listen.

What are your other passions besides music?

Well, cooking! I’m not an expert, but I love to make the dishes of the South Carolina lowcountry (lots of grits), and try new things, too.

Where and when are you at your most creative?

On the one hand, the answer to that is clearly: in the collaborative space I share with my colleagues — librettists, writers, designers, teachers, and students. But that could be a variety of places, and these days sometimes it ends up being non-places like “on Zoom.” If I am a bit more literal about it, I can offer up a real location. It’s Joe’s Chapel, a studio I created in the woods of northern Westchester County outside of New York City. It is a simple cabin with a grand piano, a desk and a chalkboard, surrounded by green. It is named after my father, who died in 2018. In the summer of 2020, during the pandemic lockdown, I wrote a 40 minute piano cycle called “Songs from Joe’s Chapel,” also in his honor. Joe’s Chapel is where I go now to create — there’s nothing like it.

Thomas Cabaniss (b. Charleston SC, 1962) is a composer for dance, theater, film, and the concert stage. Cabaniss helped to create the Lullaby Project at Carnegie Hall, serving young parents in shelters, hospitals, and prisons with collaboratively created songs for their children. He has been teaching at Juilliard in the Dance Division since 1998 and in the Music Division since 2007. He served as education director for the New York Philharmonic and Music Animateur at the Philadelphia Orchestra. He has written articles for Chamber Music Magazine and the Teaching Artist Journal. His music is published by Boosey & Hawkes, European American Music, G. Schirmer, and musiCreate publiCations. He is a member of ASCAP and an associated artist of Target Margin Theater.