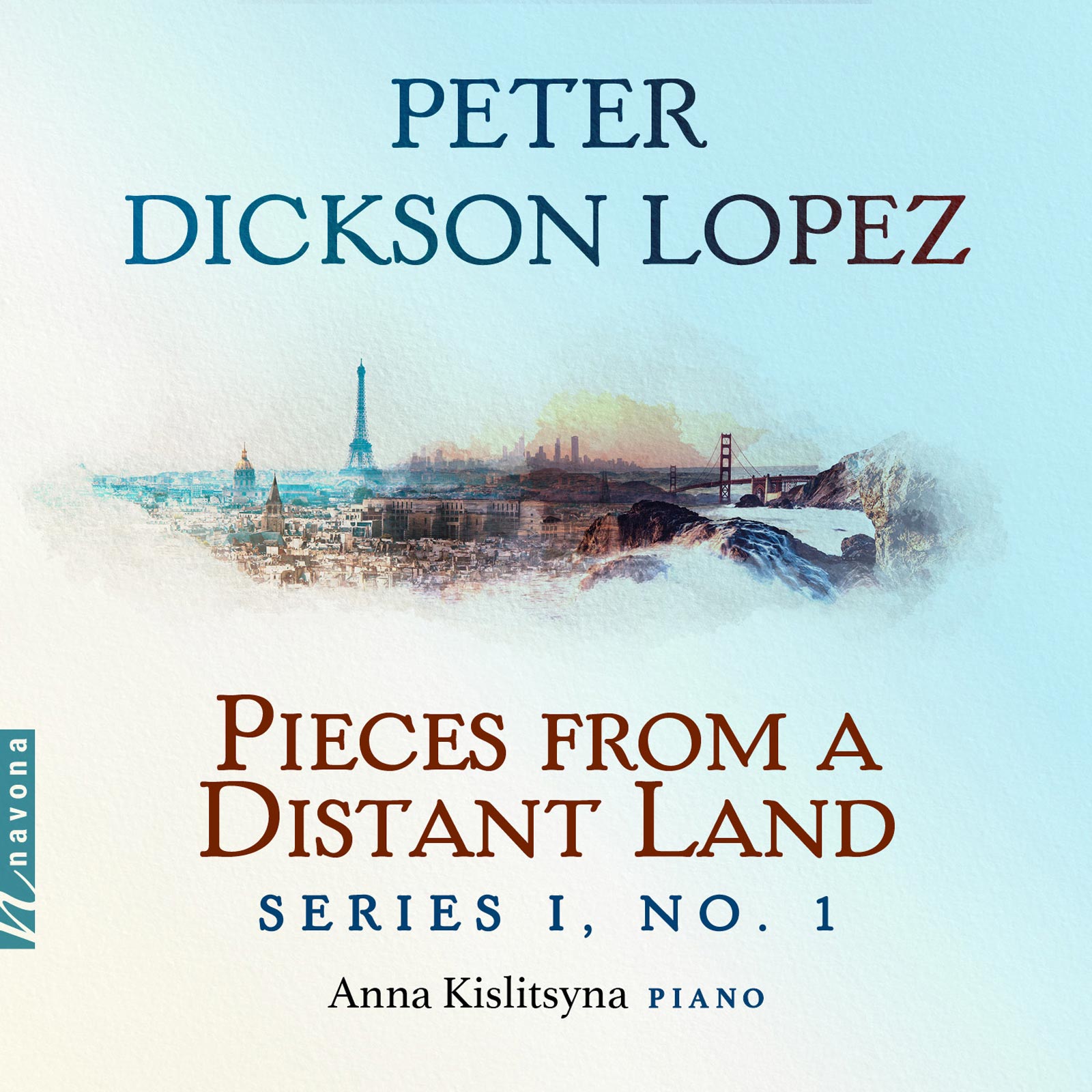

Peter Dickson Lopez returns to Navona Records with his first solo release; PIECES FROM A DISTANT LAND, a touching solo piano memoriam to his late mother, who had once requested piano pieces for herself to play at church. A touching and emotionally prolific piece given a loving performance by Anna Kislitsyna, Lopez — an ever-experimental composer — channels the “Distant Land” of tonal music familiar to his childhood self and compositional roots, while still honoring the special and often haunting sound so intimate to his musical oeuvre

Today, Peter is our featured artist in the “Inside Story,” a blog series exploring the inner workings and personalities of our composers and performers. Read on to learn about his extensive experience in music and technology and how he discovered and embraced his own compositional voice…

If you weren’t a musician, what would you be doing?

Technology.

Certain vicissitudes of life caused me to follow a nonmusician’s path very early in my career as a young emerging composer. Thus, I can say that such a question is not just speculative contemplation on my part. For about two decades, I branched out into the technology sector becoming a network engineer and programmer among other things. In the mid 1980s, I first started to develop a music programming language in the Forth and Assembler languages. I included a MIDI programming interface, and serial device control among other utilities. After marketing the product nationally, I gave up on this project as the only customers who were interested were scientist and engineer types. From there, I expanded my technology expertise to include Network Engineering in both Novell and Microsoft, and naturally I transitioned my programming knowledge to business software and applications. Near the end of this professional detour, I began to feel the loss of expressing myself in music and working with other like-minded people.

What advice would you give to your younger self if given the chance?

Listen to others but follow your own vision regardless of what others say.

During graduate school, I knew what the goal or vision of my music compositions would be: a combination of breadth, poetry, voice, passion, and spirituality. I enjoyed a very successful and initial series of professional performances in 1978–1979 of The Ship of Death in the Netherlands and San Francisco Bay Area. Indeed, The Ship of Death, a 40-minute work for male voice, chamber orchestra, and live electronics, marked the inaugural statement of an artistic vision I had long held secretly. By this time, I had numerous large projects in mind, which I still have to this day that remain unfinished. I began to get feedback from various corners that I should do shorter works that would be more accessible and easier to perform. Being by nature very open to advice, I decided to go that route. However, instead of feeling accomplished with these smaller works and gaining notoriety and acceptance, I felt too constrained emotionally, securing fewer performances, and I discovered that the music I was composing wasn’t really all that vital to me. This lack of fulfillment may in fact have been a factor in leading me away from composition for the next two decades. So, the moral of the story really is that I should not have waivered from my initial impetus and drive to compose what was (and still is) closest to my heart!

What emotions do you hope listeners will experience after hearing your work?

A kaleidoscope of emotions.

My works tend to encompass a tapestry of emotions that intertwine in a delicate fabric of sound. There may be local sections that might strike one as singularly aggressive, joyful, contemplative, or poignant for example. However, emotions in my music tend to be expressed in an almost stream of consciousness — even contrapuntal — fashion rather than as a stylized “set” piece focused on one emotional expression. Thus, if listeners come away with a sense of having experienced an amalgam of emotions, I would say that they are getting the message. Why is this so? This is simply my way of expressing life as I have experienced it, where both grief, joy, and myriad other emotions coexist as an integral part of the human condition.

How have your influences changed as you grow as a musician?

From external to internal.

I started writing music when I began playing the piano around the age of 7 or 8. Naturally I would use pieces that I was playing as templates and examples. By graduate school, incorporating such external influences was both common and expected for young composition students. I had performed Berg’s Opus 1 Piano Sonata previously at an undergraduate concert, so it is not surprising that my first major piano work in graduate school, Adagio No. 1, was very influenced by Berg. Berg’s Sonata is highly emotional and expressive, blending advanced tonality with quartal harmonies and 4:3 tuplets, and this is what really influenced me at the time. As I listened to and studied more and more scores, I picked what I thought were interesting techniques and tools to use for myself. Beyond merely incorporating these techniques, I would redesign how they would work for me and not just use them the way the source composer did. As I continued to mature as a composer, I found that this ratio of influences reversed: I began more and more to follow my “inner ear” and regard the works of other composers less and less. I would say that the three composers who most influenced me early on were Bach, Chopin, and Debussy. Later, composers such as Berg, Elliott Carter, Earle Brown, and the confluence of all the European composers I had listened to and admired during my Paris years would leave an indelible mark on my “inner ear!”

What’s the greatest performance you’ve ever seen, and what made it special?

IRCAM 1976–1978

In 1976, I was awarded the George Ladd Prix de Paris by the Music Department of the University of California at Berkeley (USA). This prize afforded me the opportunity to continue independent research in Paris for two years. While residing in Paris from 1976–1978, I listened to many concerts, most but not all being presented by IRCAM. These years were so immersive in contemporary music performance and composition that I honestly cannot isolate one “greatest” performance. For me, the totality of listening to so much was the “greatest” performance. I was able to hear, and sometimes see, legendary performers and composers whom I had only heard and read about: Pierre Boulez, Iannis Xenakis, Luciano Berio, Cristóbal Halffter, John Cage, and Heinz Holliger, to name just a few.

This “greatest” performance climaxed with the world premiere of the work that I had composed in Paris: The Ship of Death for Male Voice and Chamber Orchestra. This work is a setting of the eponymous poem by D. H. Lawrence. Ernest Bour conducted the Dutch Radio Chamber Orchestra with tenor John Duykers in the summer of 1978. The combined influence of the many contemporary European composers I had heard is all too evident in this work and remains with me to this day.

What musical mentor had the greatest impact on your artistic journey? Is there any wisdom they’ve imparted onto you that still resonates today?

Joaquín Nin-Culmell: “Always maintain a balance between the intellect and intuition.”

Joaquín was my mentor at U.C. Berkeley. Throughout my tenure there as a graduate student, Joaquín was ever supportive and guided me to become the composer I am today. His wit and words of wisdom will always stay with me on my journey as a composer, and in particular, his mantra that “a composer should always maintain a balance between the intellect and intuition.”

Peter Dickson Lopez traces his musical roots to a broad range of early influences including his tenure as a graduate student at the University of California at Berkeley (USA), attendance at Tanglewood (USA) as a Fellowship Composer, and as recipient of the George Ladd Prix de Paris (1976–1978). The eclectic nature of Lopez’s mature style stems no doubt from having worked directly with composers of diverse approaches and philosophies during his early years at Berkeley and Tanglewood: with Joaquin Nin-Culmell, Andrew Imbrie, Edwin Dugger, Olly Wilson, Earle Brown at UC Berkeley (1972–1978); and with Ralph Shapey and Theodore Antoniou during his Fellowship at Tanglewood (1979). Even more influential to Lopez’s artistic development was his residence in Paris where he had the opportunity to listen to many live concerts of contemporary European composers as well as to attend numerous events at IRCAM.