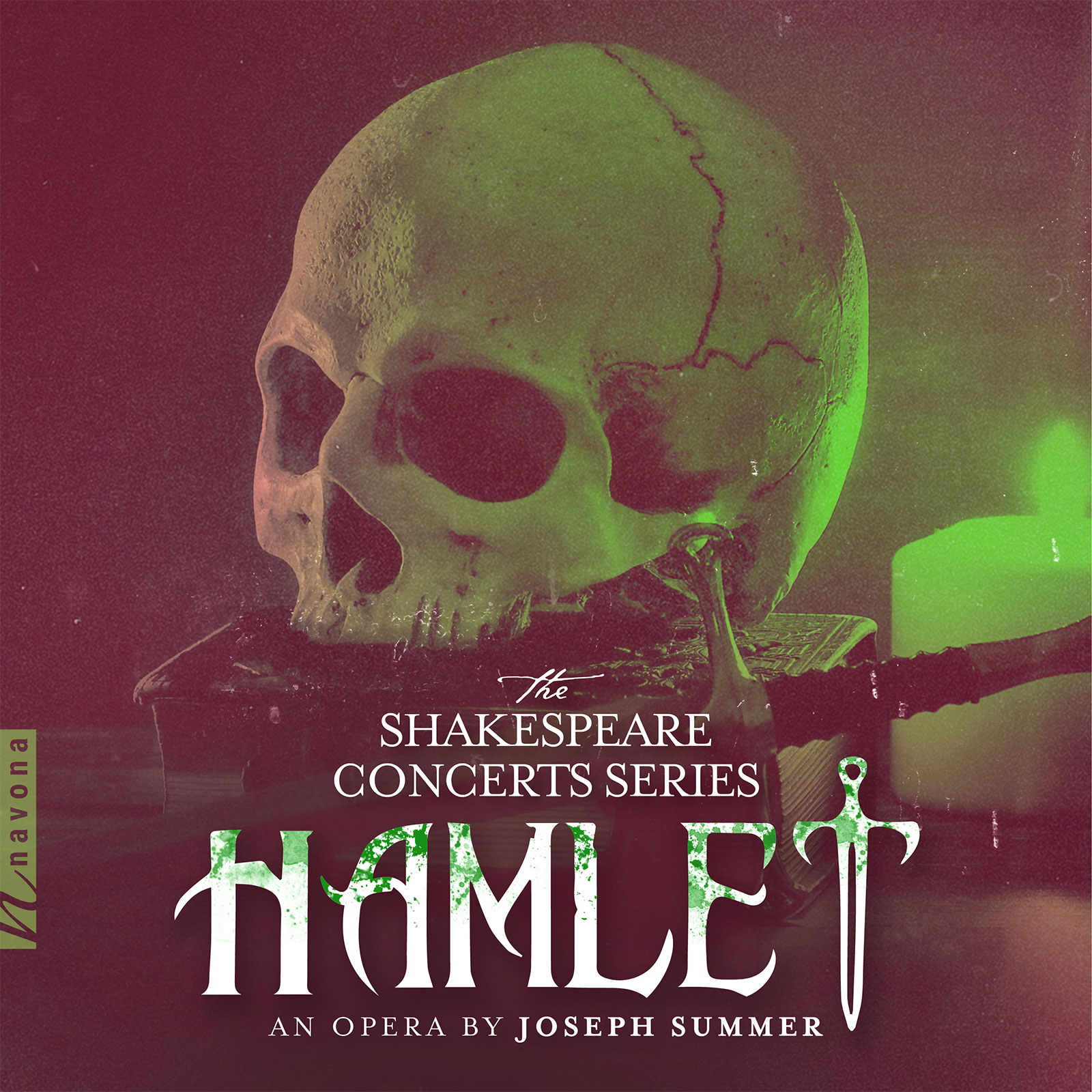

Composer Joseph Summer brings us along to Elsinore with The Bard’s classic play in an all new setting complete with the lyric integrity of Shakespeare’s words in a contemporary musical arrangement on HAMLET from Navona Records. Performed by Bulgaria’s State Opera Ruse orchestra, choir, and selected Bulgarian soloists with nine international soloists singing the lead roles, the celebrated revenge tragedy bursts with a new modern flair while keeping the spirit and riveting narrative of the original alive.

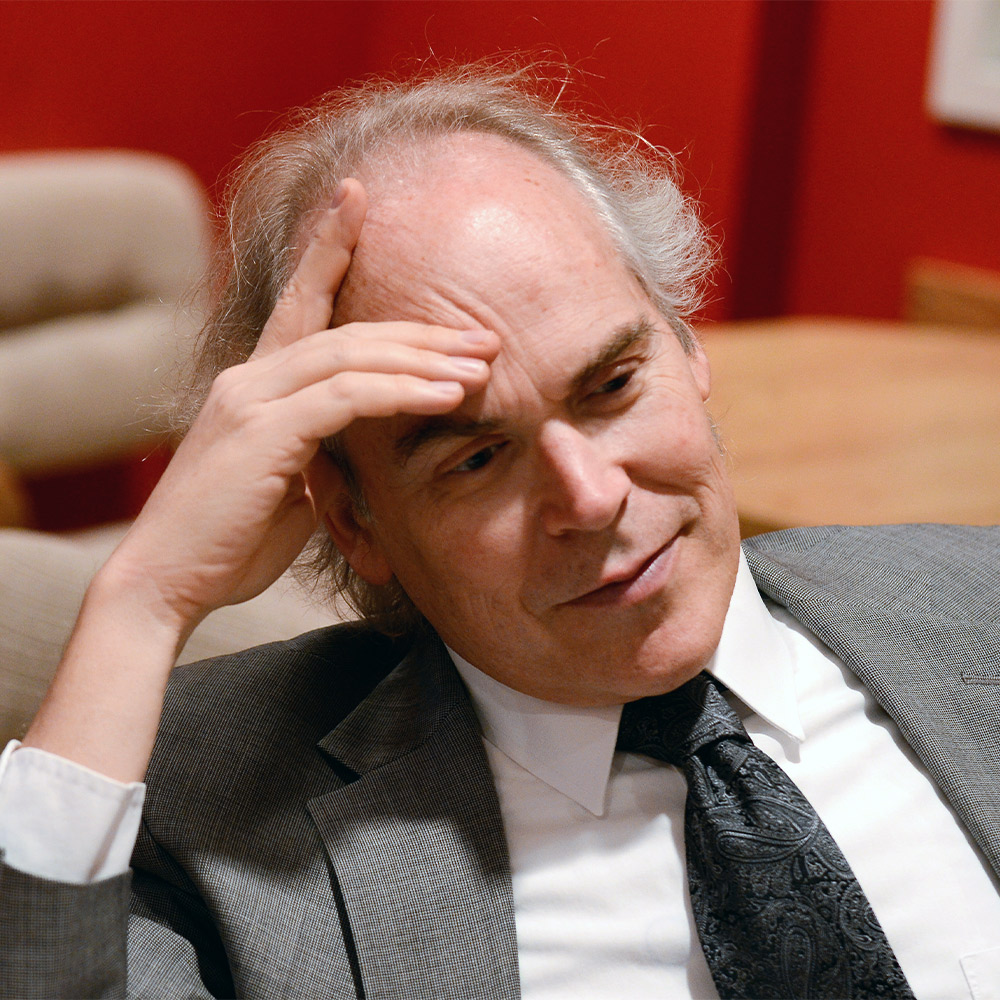

Today, Joseph is our featured artist in “The Inside Story,” a blog series exploring the inner workings and personalities of our composers and performers. Read on to learn why he had his sights set early on composition, and how his long history with the French Horn influences the intricate horn solos he composes…

When did you realize that you wanted to be an artist?

I love this question because the answer’s counterintuitive: “never.” When I was 7 years old I was asked by Betty Levine (nee Krasnopolar) the music teacher at Colfax Elementary School, a public school in Pittsburgh (back in the day when public schools often had musicians on staff) what instrument I’d like to play in the school orchestra. I said French horn, because I was obsessed with Beethoven’s 3rd. I then began composing as well, because — as I’ve related elsewhere – she gave me a blue book with music staves for exercises, and the cover pages had “how to write music” emblazoned on it, with some elementary rules (such as rhythms and pitches). Subsequently, at Pittsburgh’s Center for the Musically Talented, the director, Mikhail Stolarevsky, would tell me, “Joey, write a piece for the brass ensemble,” and I would. Stolarevsky introduced me to an Oberlin Conservatory recruiter, Karl Bewig, who told me at 13 that I would come to Oberlin and study composition. He said I didn’t need to finish high school, so I matriculated at 16. At 20 I began teaching music theory at CMU, but that wasn’t composing, therefore I left academia to pursue composing full time. So, I’m an artist.

Who was your first favorite artist(s) growing up?

Dennis Brain, the avatar of French hornists. After I began playing horn, I acquired the LPs of Brain and listened incessantly. I thought someday I’d be a professional hornist. However that dream was dashed by my remarkably horrible tone. I sounded like a Heldenbassoon. Though Oberlin had recruited me into their composition program, and provided me with a full scholarship – Oberlin was way too expensive for me or my mother – I thought that I’d somehow manage to improve and transfer my major to horn. I auditioned three years in a row, unsuccessfully. I was just a terrible hornist. I did meet my wife, when I was 14 and she 16, in orchestra. We each loved Brain and loved playing horn. I was her assistant in numerous orchestras. She had a great tone. Though I never could be Brain, I am brainy.

If you could instantly have expertise performing one instrument, what instrument would that be?

French Horn. Years of trying to be a decent hornist, years of practice, years of yearning; and I never managed that most sought after desideratum. All I ever really wanted as a youth was to sit in an orchestra and play the music of the masters. Now I achieve my revenge on the instrument by writing devilishly intricate horn solos that I can play, but unfortunately with a horribly atypical sound. As I type this response, I’m composing a suite of sonnets (139, 140, and 141) for mezzo-soprano and French horn. All hornists must pay for my failure.

What was your favorite musical moment on the album?

The best aria I’ve ever written is What a Piece of Work is Man, which occurs in the second act of HAMLET. It is scored for the full orchestra, the principal tenor (Hamlet), and solo natural horn. In my setting, I imagine Horatio, at Hamlet’s behest, taking up a horn, left by the Mousetrap musician on his chair, after Claudius has run out of the play within the play. Horatio, a trousers role, a mezzo, and Hamlet’s only true friend is my wife, Lisa. In my mind’s eye, it is Lisa who accompanies me as I bemoan the plight of man. Yes, very whiny. As I am not a tenor, and Lisa no longer a hornist, and no mezzo I know can play the natural horn; our Horatio (Katherine Pracht) had to turn the horn over to Jose Antonio Higueras Lopez so that he might brilliantly accompany Omar Najmi on the album. It really should have been Lisa and me.

If you could make a living at any job in the world, what would that job be?

Composing. Despite more than 20 CDs, hundreds of performances, a fulsome public career; in my entire life I’ve made less than $30,000 as a composer. My first commission was in high school when a trombonist, Paul Girdany, wanted me to arrange several pieces for a band he had put together, and to his astonishment I said I’d do it, but only for $50 per arrangement. Because he didn’t know anyone else who could arrange 25 Or 6 To 4 for trombone, sax, horn, piano, bass guitar, and bassoon; he had to raise the money from the other band members. Since then I’ve made a paltry few shekels on commissions, though some simoleons lecturing about my music in sundry countries. My wife, after I left academia at the age of 22, with her blessing, has been the sole breadwinner since that departure. That means I’ve earned less than $1,000 a year since I was 22, including royalties. Success has come cheap. On second thought, maybe the job I’d most like to have is hornist in an excellent orchestra, but we know that could never be.

What was your most unusual performance, or the most embarrassing thing that happened to you during a performance?

Not embarrassing, but unusual: I put together a performance in Pittsburgh of a “Happening” piece, Locomotifs, in which I acted as conductor/pianist/hornist; accoutered in a blue-jean jumpsuit, while wearing a fake beard and mustache. This was a parody of a prominent Pittsburgh composer who dressed like he was slopping the hogs. He and several students who looked like him. Maybe they felt that would help with their studies. The composer and his students were all performing in the piece but had no idea I’d be appearing in costume. After stepping on stage I began the work and they all played along. Ten minutes in, three belly dancers emerged from the back of the hall: my aunt Joan Sheffler, her teenage daughter, my cousin Susan, and their belly dance friend, Mimi. As they danced, I initiated a bubble machine that sprayed the hall with thousands of luminous orbs. Five minutes later, I read a speech, a fictitious account about how the Pennsylvania and Lake Erie Train Company had commissioned three composers to write eight-hour works for their art train, to be played 24 hours a day, to promote the railroads and art. During the speech I interrupted myself to ask my mother to stand and complimented her on having such a talented son. (It was her birthday.) The performance was a smash, and the dean of Pitt musical school asked me to reprise the performance another day, but I said that it was an unrepeatable experience. It wasn’t. That was the second performance, the first was at Oberlin, just three years previously, with different extramusical elements.

Joseph Summer began playing French horn at the age of 7. While attending the Eastern Music Festival in North Carolina at age 14 he studied composition with the eminent Czech composer Karel Husa. At age 15 he was accepted at Oberlin Conservatory, studied with Richard Hoffmann, Schönberg’s amanuensis, and graduated with a B.M. in Music Composition in 1976. Recruited by Robert Page, Dean of the Music Department at Carnegie Mellon University, Summer taught music theory at CMU before leaving to pursue composition full time.