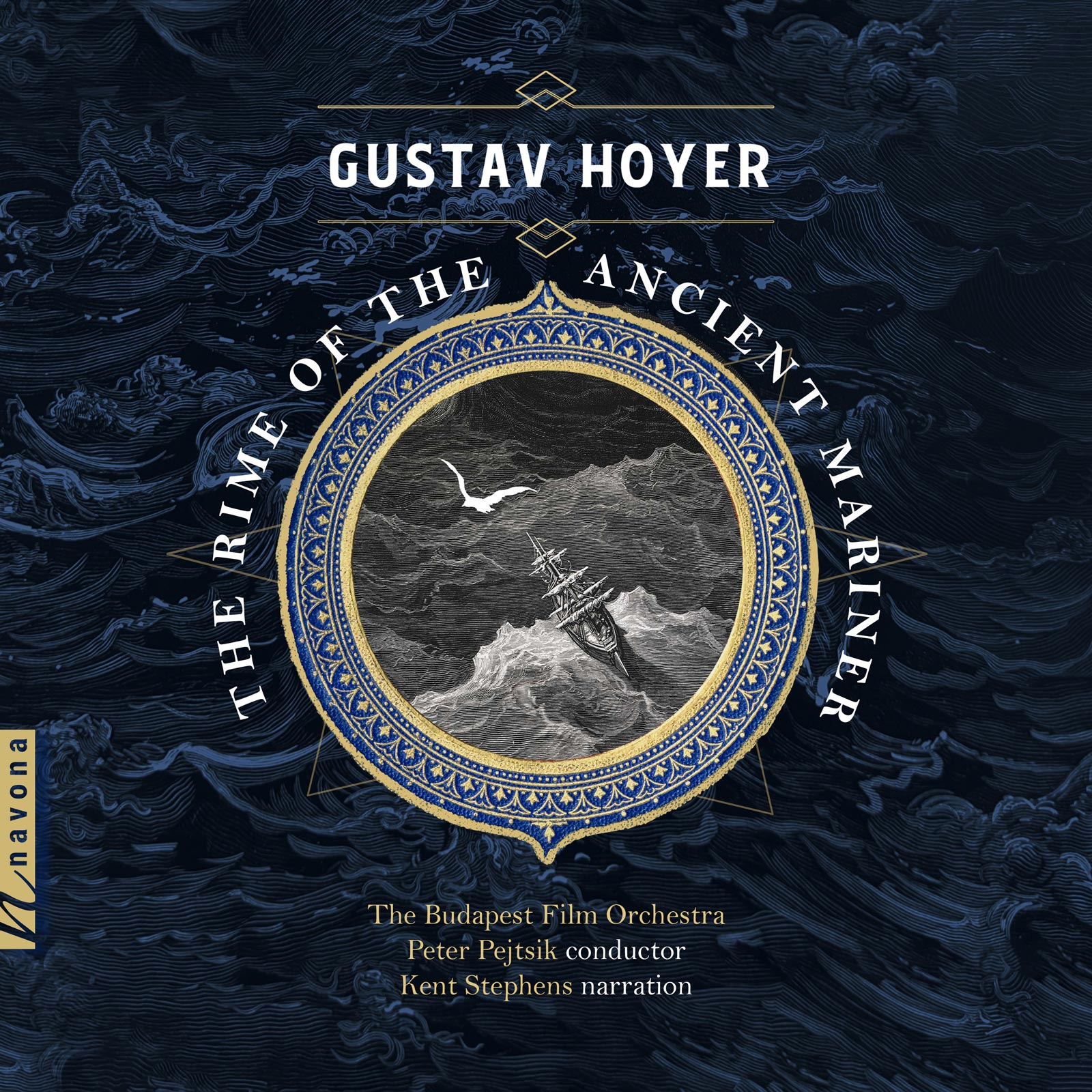

Renowned composer Gustav Hoyer comes to Navona Records with an ambitious and harrowing seven-part orchestral setting of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s THE RIME OF THE ANCIENT MARINER. Hoyer is no-holds-barred in his talent for the narrative orchestra, producing a musical journey packed with all the intensity and horror of the text from which it hails.

Today, Gustav is our featured artist in the “Inside Story,” a blog series exploring the inner workings and personalities of our composers and performers. Read on to learn his sage advice for performance preparation and why he is particularly captured by elements of timbre and orchestration…

If you could collaborate with anyone, who would it be?

There are so many world-class performing artists across different styles and instrumentation, but I would have to say Gustavo Dudamel. His musical energy and insight are amazing. It would be a privilege to have him perform my orchestral work.

What advice would you give to your younger self if given the chance?

The conservatory training I received early on was rich in theory and compositional technique. However, as a classically trained composer I fell into the trap of thinking that the dots and squiggles I put on a page were music. It took me a decade to move beyond a preoccupation with theoretical novelty and truly understand that the notation is merely instructions. It is humans who interpret those instructions to create the wondrous sound waves that caress our ears as music. I would stress the point that theory is an attempt to capture the ineffable and indescribable effect of these vibrations. I would tell my younger self to release the tyranny of the page in favor of the supremacy of the vibrating air. Don’t hide behind your technique, take the risks of stating your heart’s inspiration as directly as you can.

What emotions do you hope listeners will experience after hearing your work?

My music is architectural and narrative in nature. I almost never simply repeat a musical passage… it is always somehow altered in timbre, harmony, or texture. Often, thematic material interweaves and coexists in different combinations to continually drive the music forward. I want listeners to feel a sense of direction, purpose, and — if I should be graced to ever create music of this quality — transcendence. To hear and love music is an extraordinary part of being human and one of the great gifts that God gives us in this lifetime. To stop, and listen, with purpose: to reflect, to consider the vast mystery of what it is to exist: these are the questions whose contemplation fills my work. I hope that these things connect and resonate with those who hear it. In that, I share a special communion with those who share my wonder.

How have your influences changed as you grow as a musician?

As a musician just starting my career, I was deeply taken with intricacy and theoretical innovation. Musical architecture and contrapuntal complexity were inspiring. As I have written and composed over the years, I am increasingly captured by musical color (timbre and orchestration) and directness. This requires a different, more visceral technique. It takes courage to say simply what can be protected within the folds of intricate music. I admire those who can do it well. I still have much to learn and master.

What were your first musical experiences?

From my earliest memories, it was the sounds of my brother playing piano. I started my studies as an older teen, but the sounds of music being made in the home laid a richer foundation for my later composition than I understood at the time. He would practice and I would sit, watch, and listen. I think I absorbed much of my musical instinct through this informal study. I started piano lessons at 8 but was kicked out because of a lack of practice. I was not in a home situation with the necessary structure to help a lazy child learn the rewards of diligence at the keyboard. I would come back to the instrument as a self-taught player and would audition for entrance to the college music program as a pianist with a performance of Brahms’ Rhapsody in g-minor (Op 79, no 2). My first conducting and composition experience started two years prior in high school.

How do you prepare for a performance?

Two bits of wisdom help me prepare. One, slow practice makes for fast playing, and two, in the days before the performance, practice at the same time of day as the performance.

The first acknowledges that musical practice is ultimately about mastering the mind and its instincts. To make the thousands of miniscule muscle movements per minute that are required to execute a piece of even moderate difficulty requires a training of the mind. If you can imagine the sounds and the sensation of your body producing them, you can make any music that you want fast or slow. To train the mind is a journey for which there are no shortcuts and to master a piece, you must humble yourself before slow repetition.

The second is about the body. As cyclical creatures our daily biorhythms are anchored in the rotation of our planet on its axis, and its movement around our local star. Timing my preparatory practice to occur at the same time of day as the performance helps me use my circadian rhythms to reinforce the mental and physical efforts that will be required at the time of performing. It’s like the process of reinforcing waves in water to create more powerful and focused waves.

Gustav Hoyer was born in Denver CO in 1972. His musical pursuits began in high school following a life-changing encounter with the music of Beethoven and Mozart. He subsequently studied music theory, piano, and violin and pursued collegiate degrees in composition. He has written music for a wide variety of ensembles, media, and settings. His recorded music has been heard in film, on radio, and in performance around the world. He continues to create new orchestral music that draws on the tools of classical vocabulary while fully modern in their contemplations.