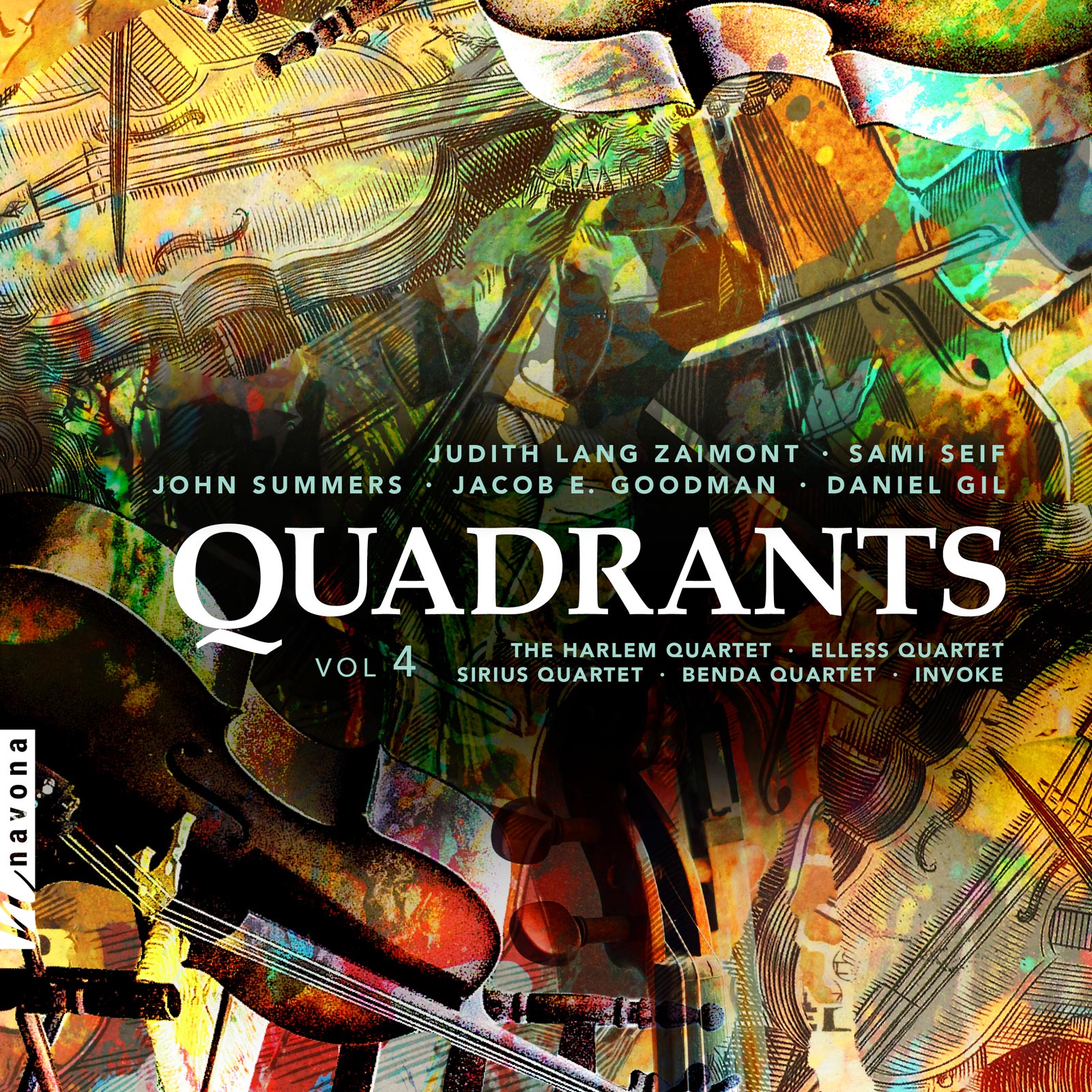

QUADRANTS VOL. 4 comes as the fourth installment of Navona’s acclaimed series of string quartet recordings by contemporary composers. This time, a variety of ensembles perform a selection of pieces by Daniel Gil, John Summers, Sami Seif, Judith Lang Zaimont, and Jacob E. Goodman, who passed away before the album’s release. Like its predecessors, QUADRANTS VOL. 4 presents musical creations that are highly structured, thoroughly conceptualized and profoundly cerebral, drawing upon subject matters as diverse as Kabbalistic philosophy, English urban poetry, and Arabic cultural identity, among others. The works presented here deliver a crystal clear view at the technical capabilities of today’s composers, and each ensemble masterfully executes the material with virtuosic panache.

PARMA Content Writer Shane Jozitis recently connected with the composers of QUADRANTS VOL 4 to learn more about the inspirations, processes, and realizations behind their works. Read on for an exclusive deep dive into the creative minds behind this Navona Records release.

SJ: Inspiration can take many shapes and come from many directions. Was your piece always intended to be a string quartet?

JZ: This commissioned piece was absolutely to be a string quartet. And its inspiration differs materially from most of my music (which is inspired by the wonders of the natural world). This first quartet is all about differing ‘views’ of its six-part motive – just as an artist’s shape on paper can be seen differently when the lighting changes, or the paper is turned.

SS: I had known all along that I wanted to write for string quartet and that I had an artistic statement to make within it. It was around Christmas 2019, I started reading “Orientalism” by Edward Said, the book which was the inspirational motor for the piece. A few months later, as I was still neck-deep into the book, the global conversation around race and racism intensified. I had been planning and sketching out the piece, and I think it was completed at a time in which people were prepared to be receptive to it.

JS: This piece, City Poem, actually comes from a failed project I attempted about 10 years ago. I ended up throwing it all out except for this piece, as it was leagues above the rest in terms of musicality and content. So it was always a string quartet arrangement, although with a vocal part as well.

SJ: Constraints can be an important part of creativity. What’s the primary driver for your expression — tradition, innovation, or perhaps a balance of both?

DG: I always start with an idea sketch; a self imposed conceptual limit. This helps me define my constraints and boundaries from the very beginning of the compositional process.

JZ: True composers know the literature — great work that has been done over time. So the inspirational challenge with a new string quartet is to offer something both new and distinct. That is, distinct enough to reveal yet another ‘embodiment’ of string quartet – and eventually fold into repertoire.

JS: I don’t consider myself as a significant composer, therefore I’m not party to the weight of tradition. It’s that simple! I have to put in a significant effort, though, to keep my head above water in the small country I live in, so my first touchstone is a subjective comparison with other composers around me. I am about to submit a chamber opera work to a company in Chicago, and the main attraction to me about this request was the limits they put on participants: 5 players (fine: guitar and string quartet) and four singers (fine again: SATB). I really look forward to opportunities like this, because they define the structure they want, and it happens to be the structure I want, too.

DG: A composer’s free expression must be unencumbered by past, present, or future notions of others’ considerations of what composition is. You must say exactly what you want, without exception. The hard part, often, is figuring out what it is you actually want. This is where the art of composition becomes a life path towards self-knowledge.

SJ: Interesting point, Daniel. What are your thoughts on the meaning of composition in general?

DG: Composition is a lifelong pursuit that starts with the discovery of superficial wants, and ends in a profound understanding of one’s own unique nature as freely expressed through music. I use graphical representations, and sometimes textual formats or a combination thereof to make a sort of map of the mind space that I want to play in; the space within which my compositional consciousness can feel free to explore. The composition which follows is never a one-to-one representation of this mind space, rather it is the result of being present within the constraints of the idea that I mapped out, and then exploring freely.

SJ: How do you focus your compositional mind into the fingers and hands of the players during the writing process?

SS: It’s hard to say what exactly the influence of performing has been on my composing, although certainly it has affected me. When I first embarked on my musical journey, I started exploring music on my own with the help of a special “Arabic keyboard” with adjustable microtonal tunings. These keyboards were designed to be flexible in accommodating the quartertones of Arabic music.

JZ: Only since 2000 has my music turned ever-more string forward. That strings are a coherent medium over a large pitch spectrum makes them just right for a composer who mainly performs on piano. It’s no accident that I have waited many decades to address the distilled medium of string quartet. It has opened worlds to me, and now – at age 77 — I’m working on my third quartet.

SS: I studied western music theory textbooks as I had no access to a teacher for the first few years of my musical education. Later, I was formally trained as a pianist, but also trained in audio engineering. Since then, I’ve sang in choir, I’ve conducted, and even performed on wineglasses. Most of my performing has been on piano and keyboards, although I wonder if using a keyboard would have been helpful for most of this piece; the extended techniques, the microtones, the independent time-layers of each player, and other such elements make this difficult to realize on a piano.

SJ: Well said, everyone. Thank you for joining this roundtable discussion of QUADRANTS VOL 4!

Daniel Gil is a composer, ethnomusicologist, producer, orchestrator, and performer. He is a graduate of Berklee College of Music and holds an MFA in composition from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Gil’s music has been described as “poignant and majestic” (Boston Globe), “beautiful and original” (Jerusalem Post), and that he “sounds like Greg Lake and Pete Townshend combined” (The Big Takeover) when singing and playing guitar with his electro-progressive band Raibard.

Sami Seif is a Lebanese composer and music theorist. His music is inspired by the aesthetics, philosophies, paradigms, and poetry of his Middle-Eastern heritage. His work has been described as “very tasteful and flavorful” with “beautiful, sensitive writing!” (Webster University Young Composers Competition).

Judith Lang Zaimont's music is often cited for its immediacy, emotion and drama. Her distinctive style-strongly expressive, sensitive to musical color and rhythmically vital-is evident in even her early music. The New York Times described it as "exquisitely crafted, vividly characterized and wholly appealing," and perhaps for these reasons her music has consistently drawn performers from around the globe and several of her works have achieved repertoire status.

John Summers began his professional composing career in 1973, writing music for schools for a touring theater company, where he produced every type of production, from educational musicals for young kids to setting curriculum poetry (Shakespeare, Eliot, etc) to music. This continued until 1977, and in the process, he visited every small and large town in the Eastern states of Australia.