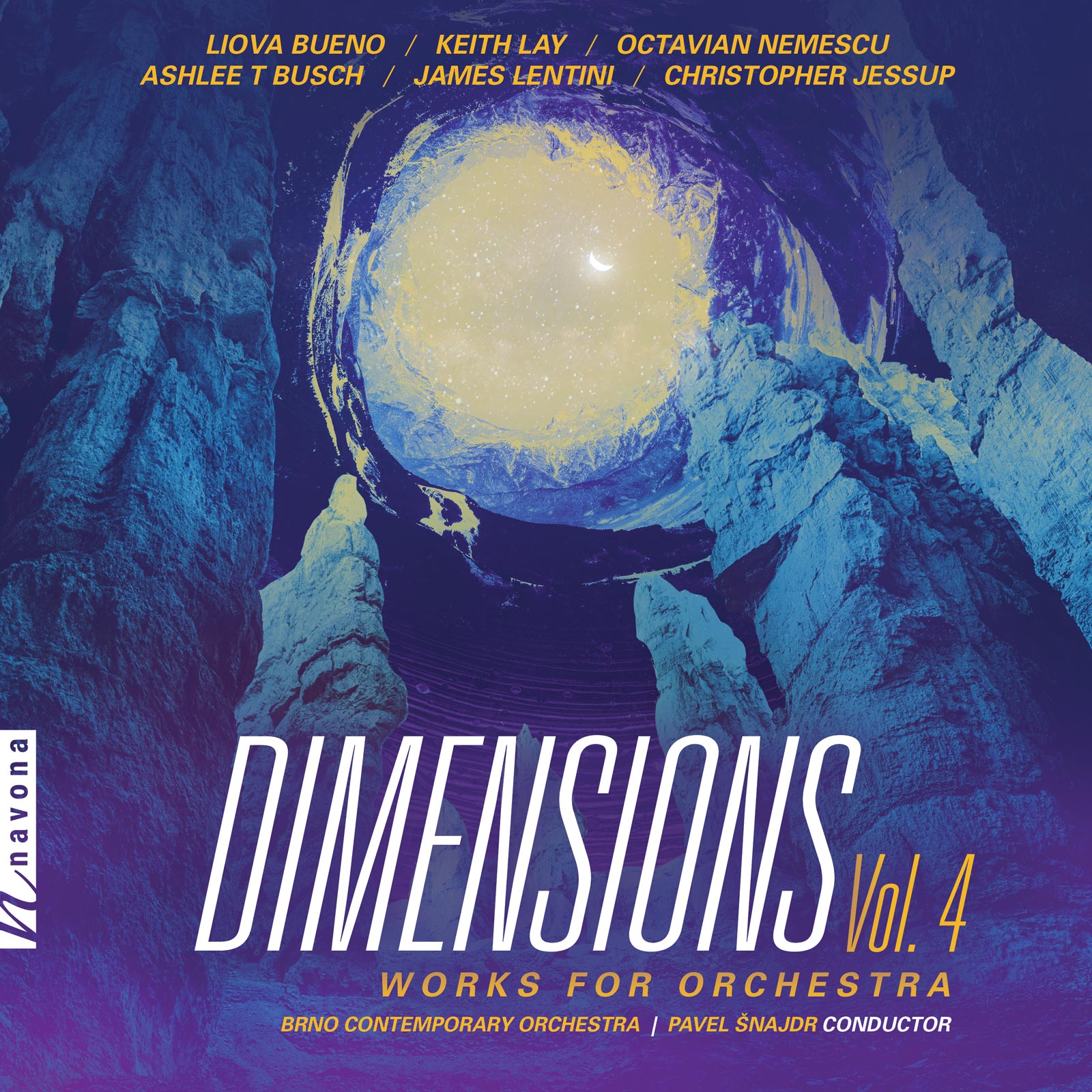

DIMENSIONS VOL. 4 gathers together a diverse collection of works for large ensemble by six lauded contemporary composers. These powerful yet intimate creations expand the boundaries of traditional chamber music while preserving the unique timbre of each individual instrument. The collection includes works like Shallow Streams by Ashlee T Busch, in which quick-moving wind, string, and percussion lines dance over the calm “riverbed” of the piano. Meanwhile, Piccola Serenata from composer Liova Bueno is a 21st-century take on a style of music composed and performed in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries, intended as light entertainment at social gatherings. These are just a few examples of the sheer breadth of DIMENSIONS VOL. 4.

PARMA Content Writer Shane Jozitis recently connected with the composers of DIMENSIONS VOL. 4 to learn more about the inspirations, processes, and realizations behind their works. Read on for an exclusive deep dive into the creative minds behind this Navona Records release.

SJ: When was the first time that you can remember an orchestra, ensemble or piece, make an impression upon you?

LB: I went to my first orchestral concert when I was seven years old, and from the first moments, I was mesmerized. I remember how it pinned me to my seat even though my body felt like it wanted to jump as high as it could. When I began composing at age 10, I keenly felt the influence of this experience, and felt that story-telling and character were crucial ingredients for music. Listeners often associate quite specific imagery, characters, or experiences with what they hear — which may or may not be anything I myself intended while writing! However, the fact that audiences respond to my music as something that makes them feel makes me very happy. I am humbled to think that I may be doing something with my own music that is akin to what I experienced myself so many years ago.

KL: Charles Ives: Music for Chorus opened my ears to the more extensive possibilities available in modern classical music. He became my role model and led me to Stravinsky, Copland, Hindemith, Varese, and other new chapters of inspiration. I borrowed, recorded, collected, devoured, and assimilated all the modern classical recordings and scores I could find. Sax playing faded out as I spent more time listening, seeking, and finding miracles. Music became my life’s primary refuge and blessing.

AB: My musical upbringing was highly typical in some ways and vastly unusual in others. However, this is the memory that stays with me: My father was a public school teacher by day and I always tagged along when he took his students to the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Downtown Los Angeles. I distinctly remember watching the Phantom of the Opera in his Masque of the Red Death garb descend with those eerie steps in the Masquerade accompanied by those terrifying simple teardrop notes in the bass and timpani. I hid behind my seat, utterly terrified. That is the first time I remember experiencing the power of music.

JL: I grew up playing guitar in rock bands in Detroit MI, which was and still is a city very rich in musical variety and talent. Notable guitar performances I heard in person that made an impression were Andrés Segovia at Ford Auditorium and Joe Pass at Baker’s Keyboard Lounge. I saw the Detroit Symphony Orchestra frequently. As a young composer, hearing Alban Berg’s Lyric Suite for string quartet was mind-blowing. I was fascinated with the musical language, ethereal sounds, and techniques.

SJ: Do you actively think about the lengthy tradition behind you when composing, or do you approach it completely fresh?

AB: Performing in a concert band is a large part of the reason I became a composer. Performing with an ensemble is an intimacy of musical communication that is difficult to find elsewhere. To make something with a group of people (whose names you perhaps don’t even know at all!) as a single, breathing entity is one of life’s little beauties. Therefore, when I first attempted large ensemble works, I wanted to recreate that experience for other young musicians. I add gentle touches of experimentalism to each work in an attempt to push the genre into the uncomfortable directions that promote musical growth and autonomy.

JL: Tradition isn’t a roadblock at all, but the repertoire certainly allows us to learn something from a great body of work, should we choose to do so. Learning how to utilize the orchestra as an “instrument” definitely takes some study and practice. Listening and seeing how Stravinsky gets such incredible sounds from the orchestra by scoring even a single chord a certain way can teach us a lot. That said, the best new pieces for orchestra are those where the individual voice of the composer shines through, no matter what tools or techniques are employed.

Completing a piece for orchestra is a big accomplishment, and so is having it recorded and released. Can you recall the emotions you felt when hearing this work performed for the first time?

JL: There is a big difference between hearing a piece while performing it vs. listening from the audience. As a performer, the focus on executing your part while listening around you doesn’t easily allow for hearing the piece as a whole. When I heard A Distant Place performed for the first time, I was delighted that the instrumental combination provided colors and textures that transcend the notes on the page, producing some surprising and unexpected moments.

SJ: How do you go about the process of trying to get your compositional mind into the hands of the players during the writing process?

CJ: I am a pianist, so including the piano in my piece was not easy. While writing, it was a constant challenge to not let the composition turn into a piano concerto, as I am unquestionably biased towards my own instrument! I was forced to look at the piano as more of a “team player” rather than a focal point of the piece. In doing so, I learned how to use the piano as a means of highlighting other instruments and certain passages, rather than having it command the spotlight as I am so used to it doing.

KL: I’ve been composing for so long, and know the instruments of the orchestra so well, I don’t really think about the process of translating my imagination to the musicians. I figure that the combination of the musicality of what they hear, what their conductor helps them understand, and what is on the page is enough. They breathe life into their part; much like what a theater or film actor does — make something on the page leap into life — in the way appropriate to enhance the story/scene/time.

AB: My processes of composition are different for every piece I write. The biggest commonality is that I don’t ask my players to do anything I won’t try myself. I’m a strong believer of Hindemith’s philosophy of learning the instrument yourself so that your writing is as organic as possible. My most satisfying musical experiences arise from co-creativity. Minimal and post-minimal music is, by nature, meant to display certain organic truths. Music is a group activity and the composer is no exception to that rule. Working with enthusiastic, graceful, and strong musicians is one of the best parts of my job.

JL: As a guitarist myself, I put the classical guitar at the center of things in A Distant Place. While it is not truly a concerto, the guitar does take several solo passages. It is most often, however, a part of the ensemble. I do think it makes a difference for a composer to have a performing background. The way a performer learns how shape phrases makes a difference in how musical ideas live and breathe. Good ideas that are rooted in strong musicality will translate well to almost any instrument. I think that composers who have a performing background will more often write music that is idiomatic for instrumentalists.

SJ: Well said, everyone. Thank you for joining this roundtable discussion on DIMENSIONS VOL. 4!

The New York Times' head critic Anthony Tommasini raved about Keith Lay as "a composer to watch for," and Gramophone magazine has described his music as "unapologetically emotional.” Lay explains, "My life's goal is to share my reverent wonder about sound and the connections to our nature made available through listening. Every new piece is a joyful opportunity to construct a fresh musical method, technique, or invention."

Multi award-winning composer and pianist Christopher Jessup is an artist of formidable prowess. Jessup has garnered acclaim for his “imaginative handling of atmosphere” [Fanfare] and his “high standard of technique” [New York Concert Review], cementing himself as one of the foremost composer-performers of his generation.

Ashlee T. Busch is a composer, performer, remixer, arranger, and educator based in Grand Rapids MI. Busch most enjoys collaborating with other artists in poetry, dance, installation art, video, and more. Such collaborations have included residencies with East Coast and Midwest universities, as an artist with Grammy-award-winning PARMA Recordings, publishing with mixed ensemble music education publisher Leading Tones LLC, publishing with digital choral music company Zintzo LLC, and collaborations with ensembles premiering her works across the United States.

Liova Bueno's music is performed in concerts and music festivals internationally, from Europe, the United States, and across Canada to countries in Central and South America. He has received commissions from and has collaborated with various ensembles, including Cuarteto de Bellas Artes (Mexico), Vox Humana Chamber Choir (Victoria, B.C.), the Victoria Choral Society (Victoria, B.C.), the London Symphony Orchestra (U.K.), the Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra (Czech Republic), BRNO Contemporary Orchestra (Czech Republic), the Illinois Modern Ensemble (Illinois), the Orquesta Sinfónica Nacional Juvenil and members of the Orquesta Sinfonica Nacional (Dominican Republic), and members of the Victoria Symphony.

Award-winning composer and classical guitarist James Lentini is a recipient of the Andrés Segovia International Composition Prize, the Atwater-Kent Composition Award (first prize), the McHugh Composition Prize, a grant from "Meet the Composer," a Hanson Institute of American Music composer-performer grant, and multiple awards from the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP).