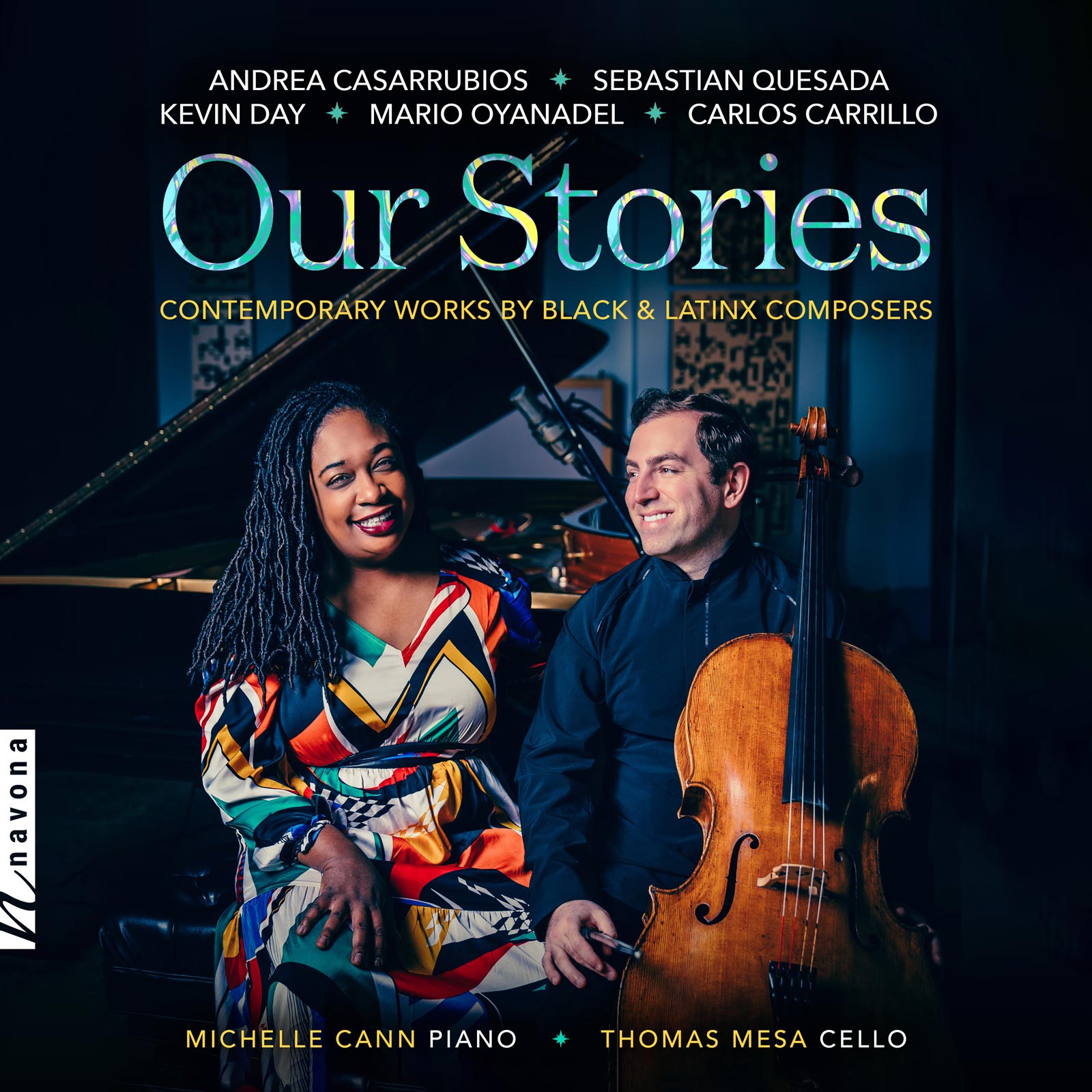

Featuring cellist Thomas Mesa and pianist Michelle Cann, OUR STORIES from Navona Records aims to raise the voices of composers and performers from backgrounds traditionally underrepresented in classical music. Made possible by PARMA Recordings and a Sphinx MPower Grant, this release musically conveys a diverse mixture of themes and topics, from the intricacies and curiosities of human communication to fear-inducing information prevalent in the media, reflections on the acceptance of life’s inevitable changes and losses, and more.

PARMA Senior Content Writer Shane Jozitis (SJ) recently connected with the composers of OUR STORIES to learn about the inspirations, processes, and realizations behind their works. Read on for an exclusive deep dive into the creative minds of Andrea Casarrubios (AC), Mario Oyanadel (MO), and Sebastian Quesada (SQ).

Collaboration between composers, performers, and audiences are an essential part of the musical experience. How do you envision your music forging connections and evoking thought and emotion in those who engage with it?

MO: How music connects with its performer and audience is, to me, a technically crucial element. I strive to control how each sound will have symbolic value for the listener, and though it is impossible to fully accomplish this, I believe this intent allows me to feel a connection with those who partake in it and recognize myself, and my music as belonging to a certain community.

SQ: I believe in the social and communal aspect of music more than anything. In other words, the creation of music is always informed by the things you see, the experiences you live, the people you meet or the conversations that you have. My music is an interpretation of all of that, like a melting pot of stimulus and reactions. Many of these stimuli come from the world to which we belong and in which we live. Music tends to reflect that. While we composers try to create from our own individuality and perspective, I think it is inevitable not to absorb, read and retrieve the events that occur in our environments. Due to the nature of this process, many of these things are expected to represent feelings and ideas shared by others. That’s the charm of new music! It is an x-ray of the essence of our time, in terms of how we think, what our concerns are, and what we can learn from others. That’s the way I envision performers and audiences interacting with my music: keeping in mind that the music is about us.

Constraints can be an important part of creativity. What’s the primary driver for your expression when writing for this instrumentation — tradition, innovation, or perhaps a balance of both?

AC: Definitely a balance of both! One can find freedom within constraints. Cello and piano are my two instruments, so it is not surprising that I feel most at home with any work that includes strings and/or piano. Performing music for this instrumentation has been, perhaps, the most educational part of my development. While studying traditional works for cello and piano duo, one becomes aware of what works best, not just in theory, but in practice on stage and with an audience. At the same time, innovation through one’s personal voice is crucial, and I think all the works in this album reflect that.

MO: Over the past four years, my specialization has centered on developing a harmonic system that emphasizes the construction of chords with intricate dissonant structures, but with an intervallic distribution that guarantees the presence of only consonant intervals within a specific range. This simple rule becomes a catalyst for innovative approaches to traditional concepts such as harmonic spectrum, polytonality, and the principles of counterpoint. By redefining these concepts to align with the system, a new extended palette of consonant and dissonant harmonies emerges, along with an enhanced understanding of the notions of consonance and dissonance.

SQ: I would say that Nerv! presents a balance between both, in terms of structure, language, and expressive forces. That tension between tradition and innovation is actually common in my work. However, the degree of implementation of each varies and depends on several factors. For some projects I may lean more towards an experimental approach, while for others I may gravitate more towards conservative languages. I see values and dangers in both, according to the vision I have about musical composition. You want to develop a personal and unique voice, but one that is not overly individualistic to the point that it isolates you from others. If you have something to say, you will want to connect with the audience through what is relevant to them, but avoiding predictability and seeking surprise, which is always a powerful element in music. In the end it is a matter of negotiation and intention that dictates what I want to do with a piece.

Are there any unique characteristics of the cello and piano that you sought to bring out through your composition, either separately or as a cohesive sound? What techniques were employed in the process?

AC: The cello often plays harmonics to resemble the melodic sounds of whistling languages. Apart from this, I wanted both instruments to have primary voices and enhance the chamber music aspect of a duo. Silbo was commissioned by the Cello Teaching Repertoire Consortium, a collective of universities and educators in the United States to expand the cello repertoire studied at conservatories. With this in mind, I wanted to make sure cellists had a wide range of techniques to master, from ricochet (a jumping bow technique) to lyrical and virtuosic passages. It was also important to me that these techniques were the result of the music, and not just techniques. This is why, through the fascinating and musical aspects of the sound of whistling languages, I was able to weave everything together. I also investigated traditional music and dance from La Gomera Island, and some of these rhythms are also included in the piece. Because whistling languages developed in regions with large extensions of land, the piano often resembles shapes of the landscape, as well as wind and sea waves.

MO: I tried to extract from the piano a sound resembling that of a bell. In this regard, you could say I treated the piano as a percussive instrument for this piece, while the cello assumed the role of carrying the melodies. However, for the final part of the piece, I utilized the natural harmonics of the cello in a manner that allowed them to harmonize with the shimmering sound of the piano, thereby enhancing it.

SQ: The piece presents a constant rhythmic drive that permeates everything. The rhythms are more unpredictable than stable, creating the feeling of nervousness that I wanted to portray as an effect of media-induced fear. The piece is energetic at its core and Tommy and Michelle did a wonderful job of bringing out the array of details and colors within it. There is a lot of layering in the outer sections of the piece, with frenetic interactions between the two instruments. The second section of the piece is based on Latin American dances, highlighting a syncopated pattern on the piano and leading to a lyrical melody on the cello. And despite the momentary suspension of this lyrical moment, the nervous rhythms are still present on the piano. Some of the techniques for the cello include percussive effects on the wood of the instrument and using a guitar pick to strum the strings.

Composers often face a blank page at the beginning of a new work. What rituals, strategies, or sources of inspiration do you rely on to overcome creative blocks and start a new composition?

AC: I actually love the image of a blank page. It is full of possibilities. I like imagining the music that will fill that space. Even if the process is daunting at times, with patience, I find it to be a process of discovery. The most stressful part, for me, is the last month or two before the delivery date of a new work! Regarding rituals or strategies, the beginning of a process needs a quiet space for me. I improvise, I listen, but above all, I investigate. I think about the instrumentation, what works best in that specific setting, I think about the commissioners and who will be performing, their sounds and personalities, the program, I envision the whole premiere as I wish for performers and audience members to experience it. This all happens before I write anything. It depends on the work and the nature of the commission, but for this specific piece, Silbo, the first couple of months were all about investigation for me. I read, listened, and spoke with communities who use whistling languages. I learned about their history and I found the whole topic fascinating. I also worked with the director of the Silbo Gomero Association in the Canary Islands, Estefanía Venus Mendoza, who was extremely helpful and excited about the collaboration.

MO: I believe this varies for every composition. In this particular one, I must say I worked quickly; the piece was likely composed within a week. This was mainly because I had a clear idea of the sound I wanted. I had chosen the theme of the three bells from Rere, and from that point on, the concept of achieving this bell-like sound from the duo came together quite rapidly.

SQ: What has worked for me with creative block is the attitude with which I face it. I try to foster a state of patience every time I start a new piece, where I keep writing no matter what until I find the idea I was looking for. While sometimes the idea comes early in the process, other times it takes a little longer. But the important thing is to write something every day, even if it’s just a few notes. Also, I don’t consider the work I did before finding that idea as a waste, but as a way to define the creative turf of the piece. If the blockage does not come at the beginning of the process but later, I follow the same strategy of writing non-stop. An important and I would say key aspect to face blockage is to appreciate and enjoy your own compositional process. I believe that adopting this attitude is to know yourself better, which leads to a more honest and authentic creative output.

Praised by The New York Times for having "traversed the palette of emotions" with "gorgeous tone and an edge of-seat intensity" and described by Diario de Menorca as an "ideal performer" that offers "elegance, displayed virtuosity, and great expressive power," Spanish-born cellist and composer Andrea Casarrubios has played as a soloist and chamber musician throughout Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas. First Prize winner of numerous international competitions and awards, Casarrubios has appeared at Carnegie Hall, Walt Disney Concert Hall, Lincoln Center, and the Piatigorsky, Ravinia, and Verbier Festivals.

Mario Oyanadel is a Chilean composer holding a B.A. in Composition from the University of Chile. His work is shaped by a diverse catalog that includes solo and ensemble chamber music, orchestral works, interdisciplinary pieces, scenic music, and performance. He has participated in various festivals including the Thailand Contemporary Music Festival, the Alba Rosa Viva! Festival, the University of Chili Contemporary Music Festival, among others. He has also received numerous international and national awards such as 1st place in the “Composition Contest Luis Advis 2017,” Chile.

Sebastian Quesada is a Costa Rican composer interested in exploring the ambiguous and subjective nature of music to evoke specific imagery. Through a blend of diverse genres and processes, his compositions aim to explore musical narratives that are connected to our cultural and social perceptions. His work spans a variety of media, including large and chamber ensembles, rock music, incidental works, installations, and more. This diverse range of mediums has contributed to his intention of synthesizing different elements to explore extra-musical concepts.