Ester, Liberatrice del Popolo Ebreo

Alessandro Stradella (1643 – 1682) Composer

Jessica Gould Ester

Sonia Tedla Speranza Celeste

José Lemos Mardocheo

Gabriele Lombardi Aman

Salvo Vitale Assuero

Anna Piroli Ebrea I

Maria Dalia Albertini Ebrea II & Act II Testo

Guglielmo Buonsanti Testo

Chorus

Anna Piroli, Maria Dalia Albertini, Elena Biscuola, Riccardo Pisani, Guglielmo Buonsanti

Camerata Grimani

Jory Vinikour harpsichord, organ, and musical direction

Lorenzo Gugole violin

Diego Castelli violin

Marina Bonetti harp

Andrea Damiani lute

Francesco Tomei viola da gamba & violone in G

The groundbreaking Roman composer Alessandro Stradella’s unjustly neglected oratorio ESTER, LIBERATRICE DEL POPOLO EBREO shines forth in a sparkling new release from Navona Records. Exploring themes of courage, self acceptance, ambition, justice, and power, this piece tells the story of Esther, a timid girl, secret Jew, and Persian Queen, who summons the bravery to save her people from annihilation. While the oratorio derives its narrative from the old testament’s The Book of Esther, this compelling story of a lone woman challenging an oppressive tyrant is sure to strike a chord, resonating powerfully for modern listeners as it recalls many ongoing conflicts in our world today.

Listen

Stream/Buy

Choose your platform

Experience in Immersive Audio

This album is available in spatial audio on compatible devices.

Stream now on Apple Music, Tidal, and Amazon Music.

Performance Video

Miei fidi pensieri

Track Listing & Credits

| # | Title | Composer | Performer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Di strage, di morte | Alessandro Stradella | Anna Piroli, soprano; Elena Biscuola, alto; Guglielmo Buonsanti, bass; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 1:25 |

| 02 | E qual cruda vendetta | Alessandro Stradella | Anna Piroli, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:58 |

| 03 | Armati sol d’otraggio | Alessandro Stradella | Anna Piroli, soprano; Elena Biscuola, alto; Riccardo Pisani, baritone; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 1:51 |

| 04 | Così dicea piangendo | Alessandro Stradella | Guglielmo Buonsanti, bass; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 1:27 |

| 05 | No, no, non disperate | Alessandro Stradella | Sonia Tedla, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Lorenzo Gugole, Diego Castelli - violins; Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 4:04 |

| 06 | S’una strage mortal | Alessandro Stradella | Sonia Tedla, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Lorenzo Gugole, Diego Castelli - violins; Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 2:04 |

| 07 | Se spera un infelice | Alessandro Stradella | Sonia Tedla, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:57 |

| 08 | Quanto vuol tanto può | Alessandro Stradella | Anna Piroli, soprano; Maria Dalia Albertini, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Lorenzo Gugole, Diego Castelli - violins; Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 2:27 |

| 09 | Udite | Alessandro Stradella | Gabriele Lombardi, baritone; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 1:49 |

| 10 | Dall’indico all’etiopico | Alessandro Stradella | Gabriele Lombardi, baritone; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo, Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:54 |

| 11 | O furie | Alessandro Stradella | Gabriele Lombardi, baritone; Camerata Grimani | Lorenzo Gugole, Diego Castelli - violins; Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:51 |

| 12 | Giunsero alla regina | Alessandro Stradella | Guglielmo Buonsanti, bass; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:32 |

| 13 | Vanne ai piè | Alessandro Stradella | José Lemos, countertenor; Camerata Grimani | Lorenzo Gugole, Diego Castelli - violins; Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 1:07 |

| 14 | Se non chiamata | Alessandro Stradella | Jessica Gould, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 1:21 |

| 15 | Fia tuo vanto | Alessandro Stradella | José Lemos, countertenor; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 1:07 |

| 16 | Richiamai spirti generosi | Alessandro Stradella | José Lemos, countertenor; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:24 |

| 17 | Miei fidi pensieri | Alessandro Stradella | Jessica Gould, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Lorenzo Gugole, Diego Castelli - violins; Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 3:43 |

| 18 | Si, si, ardita e costante | Alessandro Stradella | Jessica Gould, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:45 |

| 19 | Su dunque | Alessandro Stradella | Jessica Gould, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Lorenzo Gugole, Diego Castelli - violins; Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 2:01 |

| 20 | Che pensate | Alessandro Stradella | Jessica Gould, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:10 |

| 21 | E perchè il mio Re | Alessandro Stradella | Jessica Gould, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Lorenzo Gugole, Diego Castelli - violins; Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:59 |

| 22 | Ma si speri o disperi | Alessandro Stradella | Jessica Gould, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Lorenzo Gugole, Diego Castelli - violins; Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 1:18 |

| 23 | Così risolse la Regina | Alessandro Stradella | Guglielmo Buonsanti, bass; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:29 |

| 24 | Deh, pietoso | Alessandro Stradella | Anna Piroli, soprano; Maria Dalia Albertini, soprano; Guglielmo Buonsanti, bass; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 2:07 |

| 25 | Signor a te accorron | Alessandro Stradella | Guglielmo Buonsanti, bass; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:28 |

| 26 | Che da sì gran ruina | Alessandro Stradella | Chorus; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 1:28 |

| 27 | Piangete | Alessandro Stradella | Gabriele Lombardi, baritone; Camerata Grimani | Lorenzo Gugole, Diego Castelli - violins; Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ | 3:29 |

| 28 | Aman quegli infelici | Alessandro Stradella | Guglielmo Buonsanti, bass; Sonia Tedla, soprano; Gabriele Lombardi, baritone; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 2:20 |

| 29 | Un cor giusto | Alessandro Stradella | Sonia Tedla, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:44 |

| 30 | Impossibile non fia | Alessandro Stradella | Gabriele Lombardi, baritone; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 1:49 |

| 31 | Armati pur | Alessandro Stradella | Sonia Tedla, soprano; Gabriele Lombardi, baritone; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 1:52 |

| 32 | Ecco a’ tuoi piedi | Alessandro Stradella | Jessica Gould, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 1:24 |

| 33 | Chiedi pur | Alessandro Stradella | Salvo Vitale, bass | Camerata Grimani; Lorenzo Gugole, Diego Castelli - violins; Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 2:43 |

| 34 | Sol ti chieggio | Alessandro Stradella | Jessica Gould, soprano; Salvo Vitale, bass; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:52 |

| 35 | Serba ad altro | Alessandro Stradella | Gabriele Lombardi, baritone; Camerata Grimani | Lorenzo Gugole, Diego Castelli - violins; Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 2:28 |

| 36 | Disse Aman | Alessandro Stradella | Maria Dalia Albertini, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:30 |

| 37 | Hor palesa | Alessandro Stradella | Salvo Vitale, bass; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:29 |

| 38 | Supplicante | Alessandro Stradella | Jessica Gould, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 2:09 |

| 39 | Convien Signor | Alessandro Stradella | Jessica Gould, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:50 |

| 40 | Se agli occhi tuoi | Alessandro Stradella | Jessica Gould, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 2:48 |

| 41 | Questi sono i miei prieghi | Alessandro Stradella | Jessica Gould, soprano; Gabriele Lombardi, baritone; Salvo Vitale, bass; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 5:49 |

| 42 | Apprendete da me | Alessandro Stradella | Gabriele Lombardi, baritone; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 2:14 |

| 43 | Ah temerario | Alessandro Stradella | Salvo Vitale, bass; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:46 |

| 44 | Non dimorate più | Alessandro Stradella | Salvo Vitale, bass; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:45 |

| 45 | Cada pera mora | Alessandro Stradella | Chorus; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:43 |

| 46 | Dove più ti rivolgi | Alessandro Stradella | Sonia Tedla, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 1:13 |

| 47 | Con speranza di riposo | Alessandro Stradella | Sonia Tedla, soprano; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 1:35 |

| 48 | E qual più strano fato | Alessandro Stradella | Gabriele Lombardi, baritone; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 3:41 |

| 49 | Cada pera mora | Alessandro Stradella | Chorus; Camerata Grimani | Andrea Damiani, theorbo; Marina Bonetti, harp; Francesco Tomei, viola da gamba & violone; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord, organ & music direction | 0:46 |

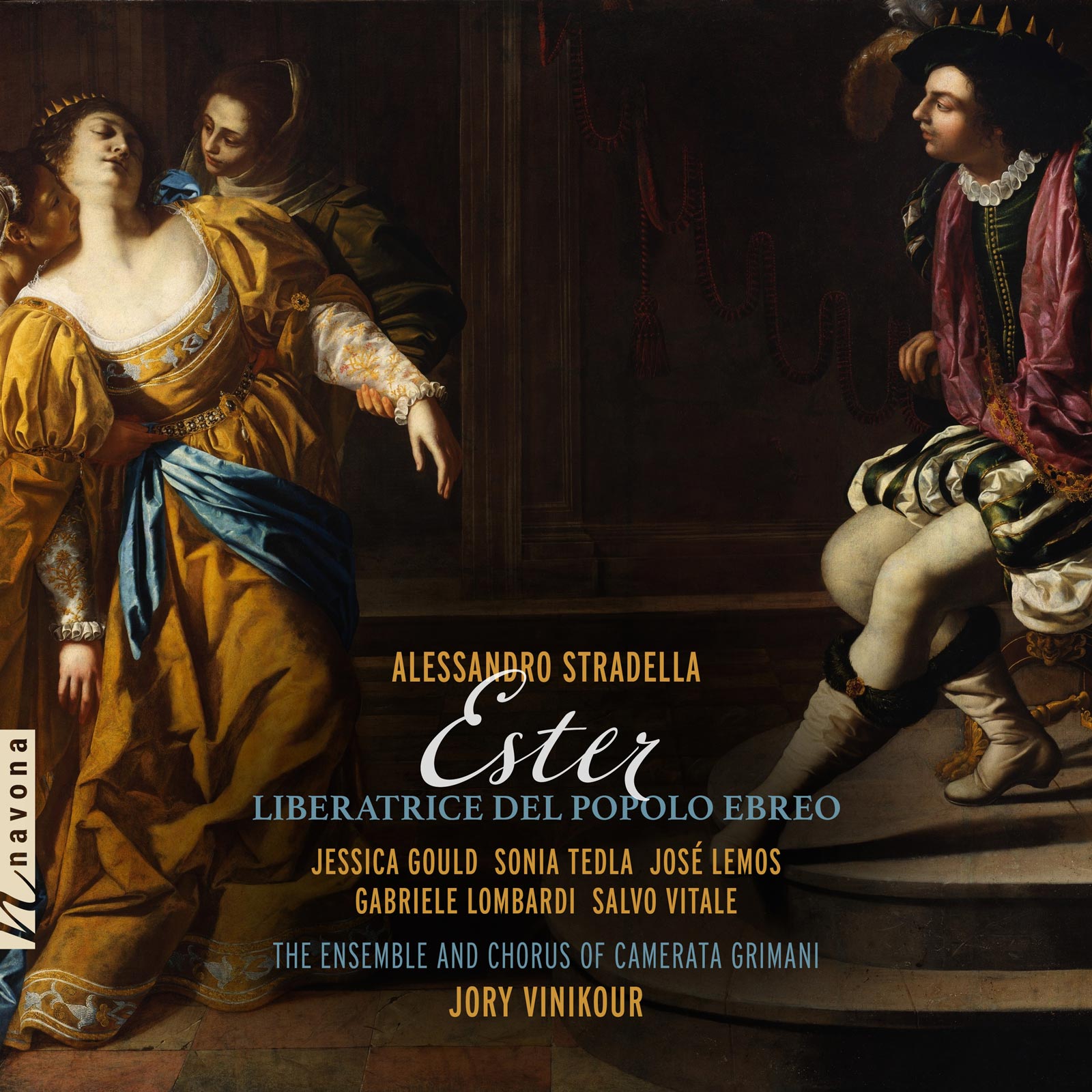

Cover Image: Artemisia Gentileschi (1593 Rome – c.1654 Naples) Esther before Ahasuerus (c.1630) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Ester, Liberatrice del Popolo Ebreo was made possible by Salon Sanctuary Concerts with generous support from NYU Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò, the Charles Schwartz Foundation for Music, Mr. Ethan Garber, and several private foundations and anonymous individual donors.

Libretto by Lelio Orsini

Recorded in 2023 at Sala della Carità in Padova, Italy

Recording Session Producer & Engineer Fabio Framba

Mixing & Mastering Fabio Framba

Immersive Audio Engineer Fabio Framba

Keyboard instruments by Francesco Zanotto

Single keyboard Italian harpsichord F.Gazzola anonymous Venetian seventeenth century copy

Organo a Cassapanca (Truheorgel)

Executive Producer Bob Lord

VP of A&R Brandon MacNeil

A&R Ivana Hauser

VP of Production Jan Košulič

Audio Director Lucas Paquette

VP, Design & Marketing Brett Picknell

Art Director Ryan Harrison

Design Morgan Hauber

Publicity Chelsea Kornago

Digital Marketing Manager Brett Iannucci

Artist Information

Jessica Gould

Praised for “a dramatic intensity that honored the texts” by the New York Times, soprano Jessica Gould has been noted for her “electrifying voice" (Musicweb International), “multi-hued powerful sound” (Seen and Heard International), and “beautiful interpretation” (Lute Society of America Quarterly). With repertoire spanning four centuries, her discography includes projects for Sony Classics, New World Records, and MV Cremona, among others. Recitals include concerts with lutenist Nigel North, with whom she has appeared as a guest artist on the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music Faculty Series, among others.

Sonia Tedla

Noted for “reaching the stratosphere with effervescence” (The Artsdesk.com) and “an agile and unfettered soprano,” (Olyrix) soprano Sonia Tedla regularly collaborates with and has appeared as a first choice soprano soloist under the direction of such early music maestros as Rinaldo Alessandrini, Alfredo Bernardini, Fabio Bonizzoni, Alessandro Quarta, Gianluca Capuano, Alessandro De Marchi, Federico Maria Sardelli, and Giulio Prandi.

José Lemos

José Lemos won the 2003 International Baroque Vocal Competition in Chimay, Belgium. In February 2014 Gramophone Magazine featured his solo album performance, titled Io vidi in terra with harpsichordist Jory Vinikour and lutenist Deborah Fox, saying “Lemos has effortless technical agility and uncanny word-painting.” He has appeared in operas across the globe: Tanglewood Music Festival, Zürich Opernhaus, Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, Göttingen Handel Festival, Vlaamse Opera Ghent, Opera de Nice, Haymarket Opera, Teatro Real, Théatré de Champs Elysée and many productions with BEMF — Psyche, Dido Aeneas, Carnaval de Venise and Niobe, which toured some of the most prestigious concerts halls of Europe including Auditorio Nacional de Madrid and the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam. He has also performed with William Christie’s Les Arts Florissants throughout Europe and at Lincoln Center. Lemos is a regular guest artist with the Baltimore Consort, BRIO, Pegasus Early Music, and Salon Sanctuary Concerts Music Series.

Gabriele Lombardi

Praised for “a booming voice,” (Boston Musical Intelligencer) baritone and Arezzo native Gabriele Lombardi enjoys an active career which includes collaborations with some of the most preeminent early music ensembles of our time, an extensive list which comprises Concerto Italiano conducted by Rinaldo Alessandrini, La Venexiana under the direction of Claudio Cavina, the Choir of Swiss Radio led by Diego Fasolis, Alan Curtis’ Il Complesso Barocco, Modo Antiquo directed by Federico Maria Sardelli, L’Homme Armé directed by Fabio Lombardo, Il Canto di Orfeo directed by Gianluca Capuano, among many others.

Salvo Vitale

Praised as “authoritative and darkly expressive” (Musicweb International) and for “a marvelously clear and commanding bass,” (Bachtrack), Salvo Vitale (Assuero) was born in Catania and began his vocal studies at the Scuola Civica in Milan, continuing his training with Eduardo Abumradi, Edith Martelli and Anatoli Goussev, and in masterclasses given by Alan Curtis. During his career to date, he has dedicated himself to a repertory that includes madrigals and cantatas, as well as roles in oratorios and Baroque operas.

Guglielmo Buonsanti

Bass Guglielmo Buonsanti (Testo) regularly works with many ensembles, choirs and orchestras, such as Capella Reial de Catalunya (J. Savall), De labyrintho (W. Testolin), La Cetra Barockorchester & Vokalensemble (A. Marcon), Cantar Lontano (M. Mencoboni), Vox Luminis (L. Meunier), Cantica Symphonia (G. Maletto), La Compagnia del Madridale (G. Maletto), Odhecaton (P. Da Col), Ensemble Micrologus (P. Bovi), RossoPorpora (W. Testolin), Dramatodia (A. Allegrezza). He started his musical studies in Vicenza with Margherita Dalla Vecchia. Enthusiastic about improving his music skills, he continued studying Organ and Composition at the Conservatory of Music of Vicenza. He graduated in Musicology at the University of Pavia in Cremona. In 2015 he obtained a master degree in Renaissance and Baroque singing at the Conservatory of Music of Vicenza. In 2016 he completed a master diploma in Advanced Vocal Ensemble Studies (AVES) held by Anthony Rooley and Evelyn Tubb at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis in Basel. He attended various masterclasses with significant musicians and conductors, such as D. Fratelli, R. Gini, T. Koopman, C. Hogwood, C. Stanbridge, R. Godmann, A. Bernardini, M. Radulescu, S. Mingardo, R. Alessandrini, P. Memelsdorf.

Anna Piroli

A native of Cremona, Italy, Anna Piroli, soprano is equally in demand in both early and contemporary music. As a specialist in contemporary composition, she has been entrusted with numerous premieres by such presenters as the Biennale di Venezia, IRCAM, Fondazione Spinola Banna, Kyiv National Opera, Opéra de Dijon, including such composers as Furrer, Chin, Gervasoni, Azzan, Ciceri, Ciurlo, with the ensembles Cantando Admont, Schallfeld, L’Arsenale, Divertimento Ensemble, mdi, Vox Àltera, among others. Under the direction of the legendary Jordi Savall, she has performed as both a soloist and ensemble member with his groups La Capella Reial de Catalunya, Hespèrion XXI, and Les Concerts des Nations.

Maria Dalia Albertini

After completing her studies in Renaissance and Baroque singing with top marks, praise, and honorable mention in the classes of Gloria Banditelli and Sara Mingardo, soprano Maria Dalia Albertini participates as a soloist and in ensembles in numerous reviews and concert seasons in Italy and abroad. Albertini has appeared at festivals such as Festival della Valle d’Itria, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Urbino Musica Antica, Salzburger Festspiele, Innsbrucker Festwochen der Alten Musik, Festival Oude Muziek Utrecht, with well-known ensembles dedicated to ancient music including including Dramatodía, Il Canto di Orfeo, Ghislieri Choir and Orchestra, Roman Concerto, and Voces Suaves. He has recorded for Arcana, Brilliants, Tactus, and Claves.

Marina Bonetti

Accredited internationally for her concert activity as a Basso Continuo performer, Marina Bonetti is a researcher in the field of historically informed interpretation and carries out teaching activities promoting the use of historical harps for a philological interpretation of harp music.

Andrea Damiani

Andrea Damiani has studied the lute with Diana Poulton, Anthony Bailes, and Hopkinson Smith. He has performed extensively both as soloist and continuo player on archlute and theorbo — in European countries and the United States. Damiani has recorded for and broadcast on several major European radio networks such as the BBC, ORTF, RAI, WDR, and more.

Francesco Tomei

Francesco Tomei (viola da gamba and violone), has at least 40 recordings to his credit for various record companies: Sony Classical, Sony Deutsche Harmonia Mundi, Glossa, Brilliant Classics, CPO, Hyperion, ARTS, Tactus, Symphonia, and Pan Classics. With a foundation in the “extra-classical” musical field by playing various instruments such as electric guitar, electric bass, and stick; in 1990 he began studying the double bass, working with Maestros U. Fioravanti and A. Bocini. Among other collaborations, he is the first Double bass of the Camerata Strumentale Città di Prato.Since 2002 he has combined his profession as a double bass player with the activity of a violist under the guidance of Maestro Paolo Biordi, with whom he graduated with honors in 2010.In 2015 he published his first solo CD for Sony Deutsche Harmonia Mundi with the Ensemble Bassorilievi: Trios & Quartets for Flute and Viola da gamba by G.Ph. Telemann. In June 2022, the duo CD with Paolo Biordi was released on Dynamic Records: Monsieur de Sainte-Colombe Concerts à deux violes esgales.

Jory Vinikour

Recognized as one of the outstanding harpsichordists of his generation, Jory Vinikour has cultivated a highly-diversified career that takes him to the world’s most important festivals, concert halls, and opera houses as recitalist and concerto soloist, partner to many of today’s finest instrumental and vocal artists, coaches, and conductors. First Prizes in the International Harpsichord Competitions of Warsaw (1993) and the Prague Spring Festival (1994) brought him to the public’s attention, and he has since appeared in festivals and concert series throughout much of the world.