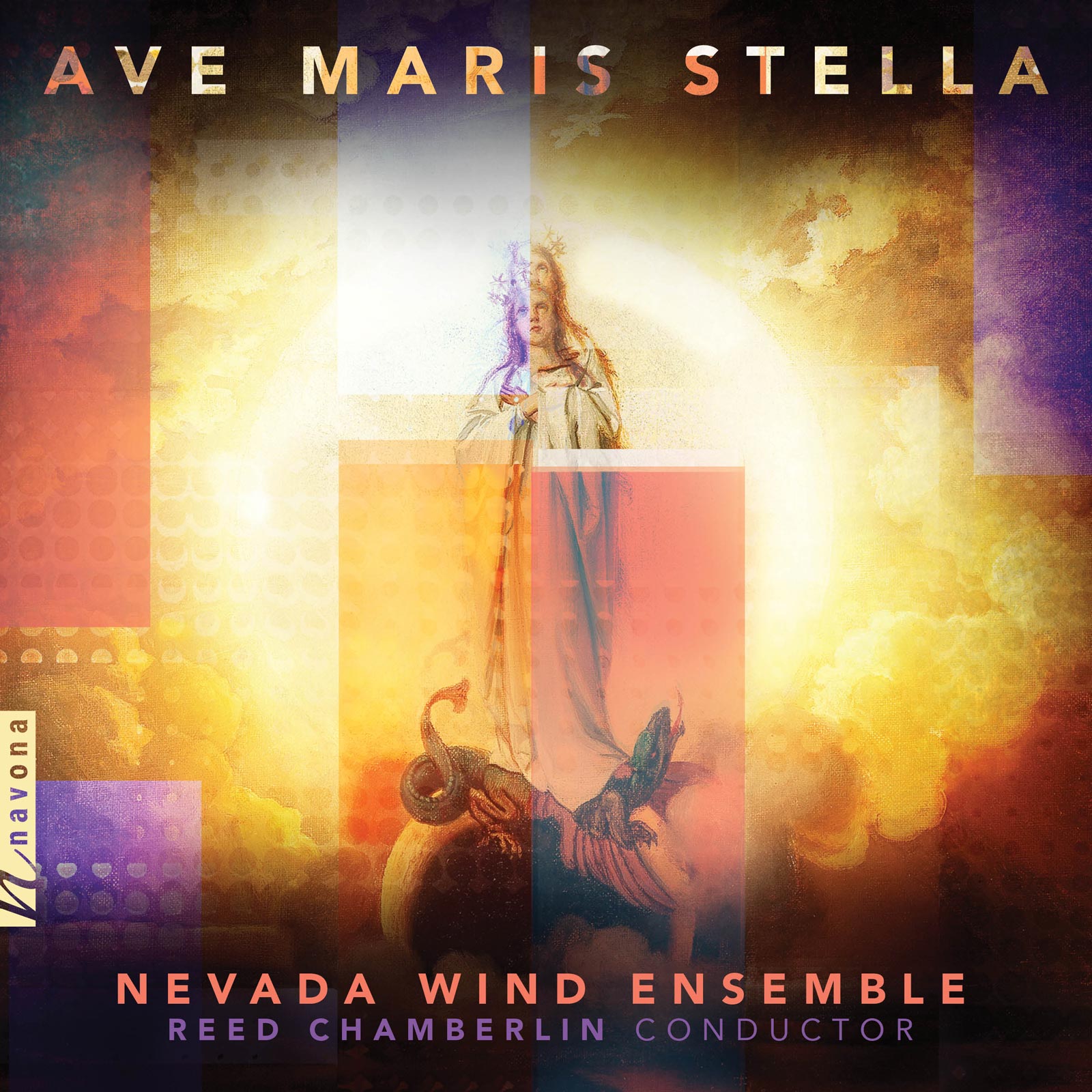

Ave Maris Stella

Nevada Wind Ensemble | Reed Chamberlin conductor

Reed Chamberlin’s AVE MARIS STELLA is a rare 21st-century recasting of beloved motets and secular works from the 14th and 16th centuries. Works by du Fay, Gabrieli, de Machaut, and more are reimagined through a double lens — the time-held tradition of setting renaissance work for wind bands, and, especially to the genre, the addition of post-production audio effects. AVE MARIS STELLA’s impressive variety of auditory experiences are recorded at such a high level of performance that it is nothing but a complete delight, from track to track and as a whole body of work.

Listen

Stream/Buy

Choose your platform

Track Listing & Credits

| # | Title | Composer | Performer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Ma fin est mon commencement | Guillaume de Machaut, arr. Reed Chamberlin | Nevada Wind Ensemble | Reed Chamberlin, conductor; Aliyah Saldarriaga, Madison Tataseo, Danika Benson - flutes | 1:28 |

| 02 | Ave Maris Stella | Guillaume du Fay, arr. Reed Chamberlin | Nevada Wind Ensemble | Reed Chamberlin, conductor; Albert Lee, tenor; Dexter Hidalgo, Robert Kiffs - soprano clarinet; Nicole Shepherd, bass clarinet | 5:16 |

| 03 | Apostolo Glorioso | Guillaume du Fay, arr. Reed Chamberlin | Nevada Wind Ensemble | Reed Chamberlin, conductor; Aliyah Saldarriaga, flute; Nicole Shepherd, Amy Kohler - soprano clarinet; Alex Fanetti, horn; Jillian Ochsendorf, trombone | 3:31 |

| 04 | O la, o che, bon echo! | Orlando di Lasso, arr. Reed Chamberlin | Nevada Wind Ensemble | Reed Chamberlin, conductor; Wyatt Wilburn, trumpet; Nathan Jones, horn; Brant Leuvano, Grady Hunt - trombones | 2:13 |

| 05 | Deo Gratias à 36 voce | Johannes Ockeghem, arr. Reed Chamberlin | Nevada Wind Ensemble | Reed Chamberlin, conductor; Danika Benson, flute; Ollie Cronick, soprano clarinet; Nicole Shepherd, bass clarinet; Ryan Stewart, soprano saxophone; Jacob Richetta, tenor saxophone; Austin Turner, baritone saxophone; Alex Fanetti, Jason Frogget - horns | 4:21 |

| 06 | Arousez vo violette | Adrian Willaert, arr. Reed Chamberlin | Nevada Wind Ensemble | Reed Chamberlin, conductor; Julien Knowles, trumpet; David Gervais, drums; Aliyah Saldarriaga, flute; Luciana Gallo, cello; Zach Howarth, Sierra Appleby, Derek Wahlenmaier - mallet percussion | 6:21 |

| 07 | Angelus domine descendit | Giovanni Gabrieli, arr. Reed Chamberlin | Nevada Wind Ensemble | Reed Chamberlin, conductor; Dexter Hidalgo, soprano clarinet; Nicole Shepherd, bass clarinet; Ryan Stewart, soprano saxophone; Jacob Richetta, tenor saxophone; Victoria Blue, horn; Tayler Duby, trumpet; Jillian Ochsendorf, tenor trombone; Brant Leuvano, bass trombone | 3:05 |

| 08 | Vecchie letrose | Adrian Willaert, arr. Reed Chamberlin | Nevada Wind Ensemble | Reed Chamberlin, conductor; Julien Knowles, trumpet; David Gervais, drums; Hans Halt, bass; Stefan Harpster, Ryan Stewart - alto saxophone; Jacob Richetta, tenor saxophone; Austin Turner; baritone saxophone | 5:56 |

Funding for this project was provided by the office of the Vice President for Research and Innovation at the University of Nevada, Reno and The University of Nevada Bands.

Music Copyright 2021 R. Reed Chamberlin

Recordings Copyright 2021 The University of Nevada, Reno

Recorded March 18-19, 2021 in Room 144 of the University Fine Arts Building, University of Nevada in Reno NV

Recording Session Producers Reed Chamberlin, Stephen Eubanks, Spencer Hannibal-Smith, Scott Miller, Darian Larsen, Max Deger

Recording & Mixing Tom Gordon, Inspired Amateur Productions

Head Engineer Raymundo Silva

Second Engineers Mike Jenkins, Alex Breckenridge

Mixed & Mastered at Imirage Sound Lab, Sparks NV

Executive Producer Bob Lord

A&R Director Brandon MacNeil

A&R Danielle Sullivan

VP of Production Jan Košulič

Audio Director Lucas Paquette

VP, Design & Marketing Brett Picknell

Art Director Ryan Harrison

Design Edward A. Fleming

Publicity Kacie Brown

Artist Information

Nevada Wind Ensemble

The nationally recognized Nevada Wind Ensemble is the flagship wind and percussion ensemble at the University of Nevada, Reno. Using one-per-part instrumentation, the Wind Ensemble performs a broad repertoire of classic and contemporary styles, ranging from large band works to chamber pieces. The ensemble tours regularly throughout the Western United States and provides the opportunity to collaborate with world-class guest conductors and guest artists. The group consists of graduate and undergraduate students.

Reed Chamberlin

Reed Chamberlin serves as director of bands at the University of Nevada, Reno, where he conducts the Nevada Wind Ensemble, teaches conducting, and guides the band program. He holds a doctor of musical arts degree in conducting from the Eastman School of Music where he was the assistant conductor of the Eastman Wind Ensemble, a Fennell Conducting Fellow, and recipient of the Walter Hagen Prize in conducting.

Notes

In 2018 I began thinking about the idea of a concept album based on the novel use of recording and editing techniques. I was considering the flexibility of instrumentation within the wind ensemble concept and the potential application of the recording process to acoustical instruments in new ways. This led me to begin to ask several questions, some creative and some pragmatic.

What assets do we have?

We have excellent facilities: outstanding acoustics in our rehearsal rooms and hall, cutting edge technology which includes a modern recording studio with Dante high speed internet which allows us to record from anywhere in the building. We have excellent recording engineers: Tom Gordon and Ray Silva, both USC educated with direct experience in the commercial recording realm in Los Angeles and in Reno, who have worked regularly with Grammy Award-winning artists. And, we have excellent and committed students. I knew our students would purposely excel at any project that I brought to them.

How could we use our facilities?

The Dante internet connection allows us to use the acoustical environment of our large ensemble space as a tracking room along with isolation booths in the recording studio. Because Dante is a zero-latency connection, we could record in real time together across these disparate physical locations. It was clear that using isolation could mean a different approach from large ensemble classical recording, similar to one used in commercial recording.

How could we best use our recording engineers?

We’ve made several successful large ensemble recordings at our University in the past, and Tom’s wheelhouse is recording commercial and popular music. This means using spot microphones, careful mixing, recording and editing drum tracks, click-tracks, and effects.

How could we further the use of electronics and technology in wind band performance and expand the boundaries of the medium?

Traditionally, the wind ensemble concept has stood for flexibility of instrumentation — a wind ensemble can be a band, a chamber ensemble, or any mixed instrumentation ensemble. Many works have been written for wind ensembles with electronics, but these are somewhat limited in scope. Most existing pieces consist of a live ensemble playing along with sounds that were synthesized or sampled. While there is value in this approach, I wanted to explore the idea of processing organic sounds generated by human beings in the wind ensemble — essentially creating an additional layer of timbre, or in this case a novel instrumentation. Ideally, this could lead to new works that must be recorded and edited to reach their full realization.

Mark Scatterday, conductor of the Eastman Wind Ensemble, suggested that I first try this idea myself, rather than commissioning a composer to write a work to achieve these goals. He also suggested that the music of the Renaissance would be a perfect vehicle. Then, as I thought about the scope of such a project, the idea lay dormant for a time until the COVID-19 pandemic. For the 2020-2021 academic year we rehearsed in small ensembles with reduced capacity and less rehearsal time as a safety precaution. We did not give live concerts to audiences. Obviously, this was not an ideal situation for our students — we use concerts as an important exhibition of their learning and musical development.

How could we create a project that would provide our students with an artistic outlet in spite of the pandemic and its restrictions?

By answering these questions, the project came together, resulting in the scoring of works for chamber groups to align with a variety of constraints and assets, including COVID-19 safety regulations, a limited and mixed instrumentation, our engineers and facilities, and the sound processing aspects available in post production. I identified musical works that would transfer well for the instruments/players that we had available, thus relying on a Renaissance practice of transcribing vocal works for winds. I then narrowed that list to pieces that had potential for generic creativity or for manipulation in post production, or both.

Each rehearsal consisted of four to five pieces in small groups, taking 20-minute breaks to clear air, and using three to four rehearsal venues at once. Rehearsals were led by myself, my graduate assistants, and were also self-directed by the student performers. The tracking sessions were comprised of two nine-hour days and had to be scheduled around safety guidelines — we recorded for 30 minutes, took a 20-minute break to clear aerosols, and then returned to record. I purposely selected pieces around five minutes or less in duration to better fit within the limited blocks of time. Because we used a player pool concept and rotated players, not all students were required to be present for the duration of the marathon days; however, the engineers, producers, and conductors were. The 20-minute air-clear breaks were used to reset microphones and routing assignments on the mixing console and Pro Tools. All of this was predetermined by our engineers who executed the sessions flawlessly.

— Reed Chamberlin