Share Album:

The New Epoch

Lucia Lin violin

Jonathan Miller cello

Diane Walsh piano

Artists are liminal figures — they cross thresholds and collapse boundaries between past, present, and future. In THE NEW EPOCH, three musicians from the Boston Artists Ensemble interpret works by French composers Fauré, Debussy, Ravel, and Lili Boulanger, infusing these pieces with unprecedented freshness and clarity.

Each celebrated in their own right, cellist Jonathan Miller, violinist Lucia Lin, and pianist Diane Walsh join forces in every duo setting possible from this assortment of instruments. Exploring works written at the threshold of the First World War — with the world crossing into the violent twentieth century and composers reacting with music that looked both nostalgically back and innovatively forward — they underline the commonalities between each composer’s unique voice and reinterpret this music for our turbulent present.

Listen

Stream/Buy

Choose your platform

Track Listing & Credits

| # | Title | Composer | Performer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Sonata for Cello and Piano: I. Prologue | Claude Debussy | Jonathan Miller, cello; Diane Walsh, piano | 4:31 |

| 02 | Sonata for Cello and Piano: II. Sérénade et Finale | Claude Debussy | Jonathan Miller, cello; Diane Walsh, piano | 7:22 |

| 03 | Sonata for Violin and Piano: I. Allegro vivo | Claude Debussy | Lucia Lin, violin; Diane Walsh, piano | 5:20 |

| 04 | Sonata for Violin and Piano: II. Intermède; Fantasque et léger | Claude Debussy | Lucia Lin, violin; Diane Walsh, piano | 4:24 |

| 05 | Sonata for Violin and Piano: III. Finale Très animé | Claude Debussy | Lucia Lin, violin; Diane Walsh, piano | 4:49 |

| 06 | Sonata for Violin and Cello: I. Allegro | Maurice Ravel | Lucia Lin, violin; Jonathan Miller, cello | 5:17 |

| 07 | Sonata for Violin and Cello: II. Très vif | Maurice Ravel | Lucia Lin, violin; Jonathan Miller, cello | 3:31 |

| 08 | Sonata for Violin and Cello: III. Lent | Maurice Ravel | Lucia Lin, violin; Jonathan Miller, cello | 6:17 |

| 09 | Sonata for Violin and Cello: IV. Vif, avec entrain | Maurice Ravel | Lucia Lin, violin; Jonathan Miller, cello | 6:11 |

| 10 | Nocturne | Lili Boulanger | Lucia Lin, violin; Diane Walsh, piano | 2:59 |

| 11 | Cortège | Lili Boulanger | Lucia Lin, violin; Diane Walsh, piano | 1:50 |

| 12 | Pièce En Forme de Habanera | Maurice Ravel | Jonathan Miller, cello; Diane Walsh, piano | 3:03 |

| 13 | Berceuse | Gabriel Fauré | Jonathan Miller, cello; Diane Walsh, piano | 3:53 |

Recorded at Mechanics Hall in Worcester MA

Editing, Mixing, Mastering, Engineer & Producer Brad Michel

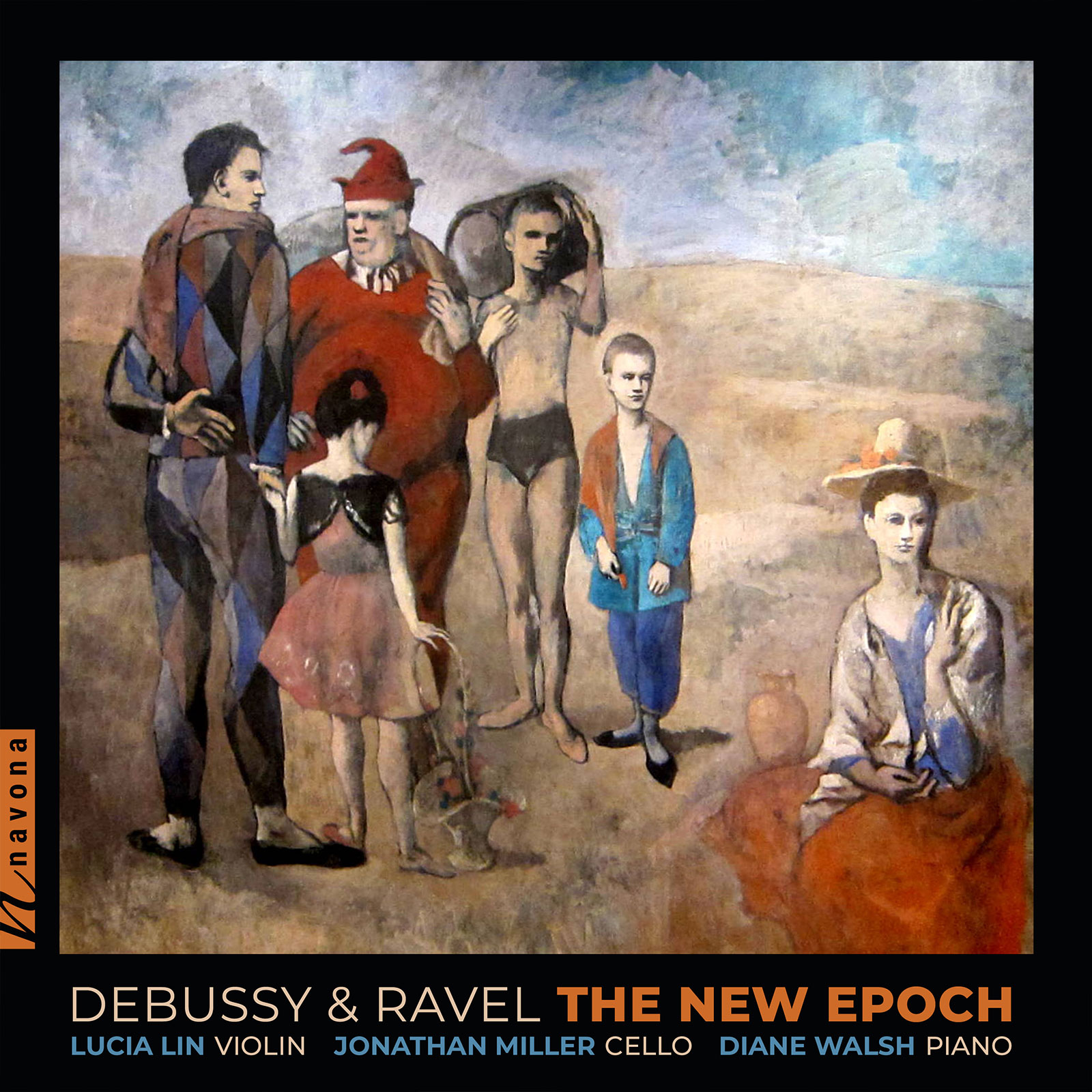

Cover Art Family of Saltimbanques (1905) by Pablo Picasso

© 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Back Cover Art Les Saltimbanques (1905) by Pablo Picasso

Violin by Pietro Guarneri of Venice, (made in) 1740

Cello “Paganini-Piatti” by Matteo Goffriller of Venice, (made in) 1700

Piano by Steinway and Sons

Executive Producer Bob Lord

A&R Director Brandon MacNeil

VP of Production Jan Košulič

Audio Director Lucas Paquette

VP, Design & Marketing Brett Picknell

Art Director Ryan Harrison

Design Edward A. Fleming, Morgan Hauber

Publicity Patrick Niland, Aidan Curran

Artist Information

Lucia Lin

Lucia Lin currently enjoys a multi-faceted career of solo engagements, chamber music performances, orchestral concerts with the BSO, and teaching at Boston University’s College of Fine Arts. Lin made her debut at age 11, performing the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto with the Chicago Symphony, then went on to be a prizewinner of numerous competitions, including the prestigious International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow. She joined the BSO at the age of 22, and has also held positions as acting concertmaster with the Milwaukee Symphony and for two years, concertmaster with the London Symphony Orchestra.

Jonathan Miller

Jonathan Miller was a pupil of Bernard Greenhouse. He is a 43-year veteran of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and has performed as a soloist with the Hartford Symphony; the Boston Pops, Cape Ann Symphony, and Newton Symphony; Symphony By The Sea, and the Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra of Boston. Miller won the Jeunesses Musicales auditions, twice toured the United States with the New York String Sextet, and appeared as a member of the Fine Arts Quartet. He performed as a featured soloist at the American Cello Congress in both 1990 and 1996.

Diane Walsh

Winner of the Munich ARD Competition and the Salzburg Mozart Competition, pianist Diane Walsh has performed concertos, solo recitals, and chamber music concerts throughout the United States and internationally. She has appeared at numerous summer festivals including Marlboro, Santa Fe, Bard, and Chesapeake, and was the artistic director of the Skaneateles Festival. She gave 113 performances of Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations on stage in the Broadway production of Moisés Kaufman’s play 33 Variations, starring Jane Fonda. A graduate of the Juilliard School and Mannes School of Music, and a Steinway Artist, Walsh has released 19 recordings of diverse repertoire from four centuries, and has taught piano and chamber music at Mannes, Vassar College, and Colby College.