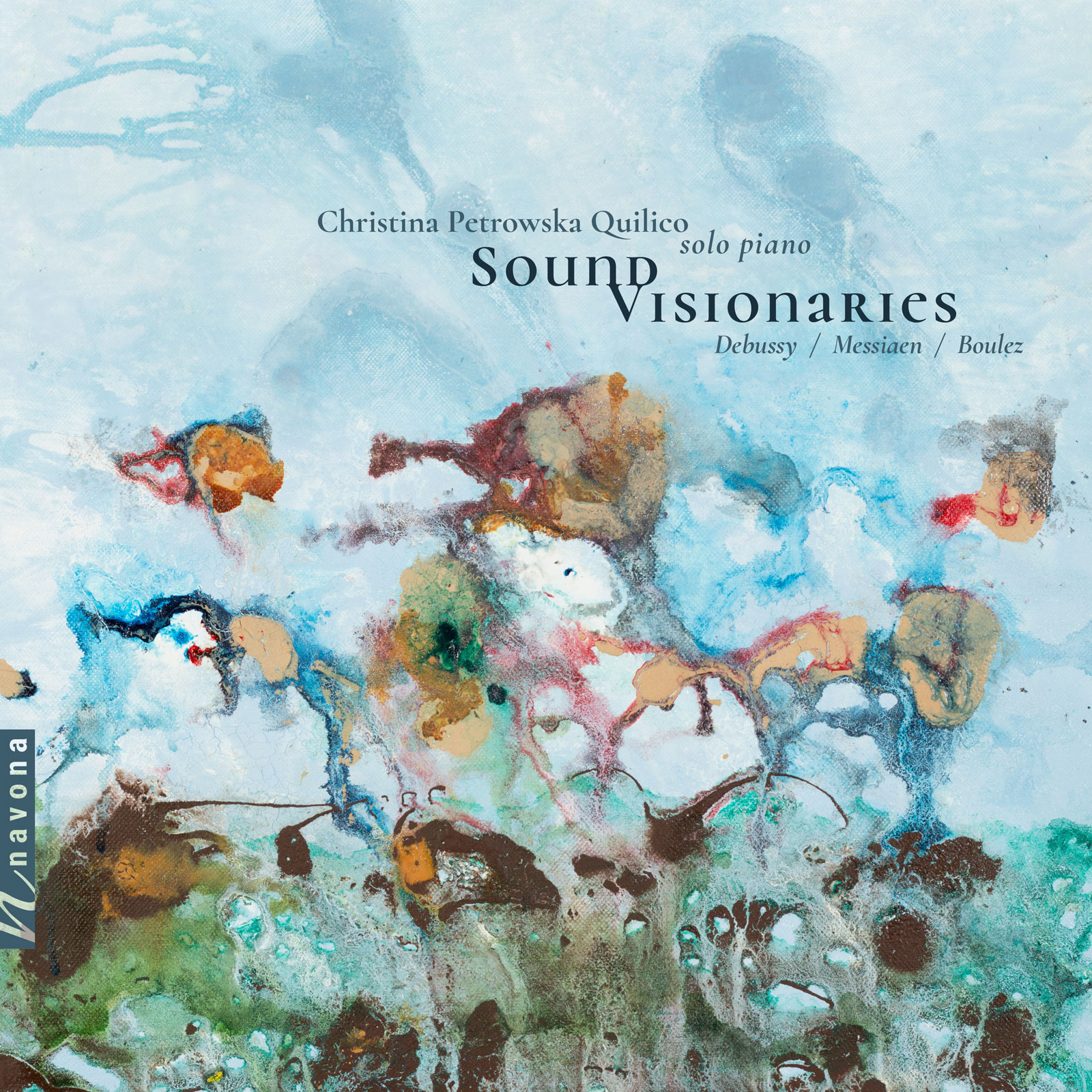

Sound Visionaries

Christina Petrowska Quilico piano

Claude Debussy composer

Olivier Messiaen composer

Pierre Boulez composer

Claude Debussy, Olivier Messiaen, and Pierre Boulez are stunningly reconciled in Christina Petrowska Quilico’s Navona Records release SOUND VISIONARIES. Boasting a track record of over 50 recorded albums and having recently been named to the Order of Canada, the veteran pianist proves that despite all difficulties, finding common ground between these three composers can be done spectacularly.

The works in question are cleverly chosen: Debussy’s ethereal Preludes, Book Two is contrasted with Messiaen’s quasi-spiritual Vingt Regards Sur L’Enfant Jésus, and the album rounds off with Boulez’s atmospheric Première Sonate and Troisième Sonate. Petrowska Quilico unearths the modernity in the impressionist, the impressionism in the mystic, and the mysticism in the modernist. Sagacious, riveting, and indeed – visionary.

Listen

Stream/Buy

Choose your platform

"Her readings are technical triumphs but then always with the utmost musicality"

Track Listing & Credits

| # | Title | Composer | Performer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Preludes, Book 2, L. 123 (Excerpts): No. 1, Brouillards | Claude Debussy | Christina Petrowska Quilico, piano | 2:24 |

| 02 | Preludes, Book 2, L. 123 (Excerpts): No. 2, Feuilles mortes | Claude Debussy | Christina Petrowska Quilico, piano | 2:42 |

| 03 | Preludes, Book 2, L. 123 (Excerpts): No. 3, La puerta del vino | Claude Debussy | Christina Petrowska Quilico, piano | 3:07 |

| 04 | Preludes, Book 2, L. 123 (Excerpts): No. 4, Les fées sont d'exquises danseuses | Claude Debussy | Christina Petrowska Quilico, piano | 2:30 |

| 05 | Preludes, Book 2, L. 123 (Excerpts): No. 7, La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune | Claude Debussy | Christina Petrowska Quilico, piano | 4:04 |

| 06 | Preludes, Book 2, L. 123 (Excerpts): No. 8, Ondine | Claude Debussy | Christina Petrowska Quilico, piano | 2:48 |

| 07 | Preludes, Book 2, L. 123 (Excerpts): No. 11, Les tierces alternées | Claude Debussy | Christina Petrowska Quilico, piano | 2:28 |

| 08 | Preludes, Book 2, L. 123 (Excerpts): No. 12, Feux d'artifice | Claude Debussy | Christina Petrowska Quilico, piano | 3:50 |

| 09 | Vingt regards sur l'enfant-Jésus, I/27 (Excerpts): No. 4, Regard de la vierge | Olivier Messiaen | Christina Petrowska Quilico, piano | 4:34 |

| 10 | Vingt regards sur l'enfant-Jésus, I/27 (Excerpts): No. 11, Première communion de la vierge | Olivier Messiaen | Christina Petrowska Quilico, piano | 5:55 |

| 11 | Vingt regards sur l'enfant-Jésus, I/27 (Excerpts): No. 16, Regard des prophètes, des bergers et des Mages | Olivier Messiaen | Christina Petrowska Quilico, piano | 3:20 |

| 12 | Vingt regards sur l'enfant-Jésus, I/27 (Excerpts): No. 2, Regard de l'étoile | Olivier Messiaen | Christina Petrowska Quilico, piano | 2:40 |

| 13 | Vingt regards sur l'enfant-Jésus, I/27 (Excerpts): No. 14, Regard des anges | Olivier Messiaen | Christina Petrowska Quilico, piano | 4:32 |

| 14 | Vingt regards sur l'enfant-Jésus, I/27 (Excerpts): No. 8, Regard des anges | Olivier Messiaen | Christina Petrowska Quilico, piano | 2:21 |

| 15 | Vingt regards sur l'enfant-Jésus, I/27 (Excerpts): No. 13, Noël | Olivier Messiaen | Christina Petrowska Quilico, piano | 3:29 |

| 16 | Piano Sonata No. 1 | Pierre Boulez | Christina Petrowska Quilico, piano | 10:15 |

| 17 | Piano Sonata No. 3: II. Trope | Pierre Boulez | Christina Petrowska Quilico, piano | 8:10 |

PRELUDES BOOK TWO & VINGT REGARDS SUR L’ENFANT-JÉSUS

Recorded at Harmonie German Canadian Club, Toronto ON, Canada

Session Producer Richard Coulter

Recording Session Engineer David Quinney

PREMIÈRE SONATE

Concert recorded live, September 2003, at the Glenn Gould Studio, Toronto ON, Canada for the Presentation of the Glenn Gould Prize to Pierre Boulez

Session Producer Mark Steinmetz

Recording Session Engineer Doug Doctor

TROISIÈME SONATE POUR PIANO

Recorded live at Walter Hall, University of Toronto in Toronto ON, Canada

Session Producer Richard Coulter

Recording Session Engineer David Quinney

Preludes, Vingt Regards, and Troisième Sonate are archival concert recordings originally aired by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Music compiling and editing David Jaeger

Publicist, program notes editor Linda Litwack

Cover Art Christina Petrowska Quilico

General Manager of Audio & Sessions Jan Košulič

Audio Director, Addtl. Mastering Lucas Paquette

Executive Producer Bob Lord

Executive A&R Sam Renshaw

A&R Director Brandon MacNeil

VP, Design & Marketing Brett Picknell

Art Director Ryan Harrison

Design Edward A. Fleming

Publicity Patrick Niland, Sara Warner

Artist Information

Christina Petrowska Quilico

“An extraordinary talent with phenomenal ability” and “dazzling virtuosity” (The New York Times), Christina Petrowska Quilico has won fans internationally for her 60 albums, solo recitals and performances of 53 piano concertos. Reviews describe her as a “piano wizard” (Take Effect Reviews), “the towering Canadian piano virtuoso” (The WholeNote), “commanding pianism” (American Record Guide), “intelligent program” (Gramophone), and her “ability to leave a permanent impression on the listener’s soul” (Sonograma Magazine). One of “Canada’s 25 best classical pianists” and in the “Concert Hall of Fame” (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation), she was appointed to the Order of Canada, Order of Ontario and the Royal Society of Canada.

Notes

All three French composers on this album were visionaries of their time. They shared an interest in Eastern music and were inspired by written art, especially the structures used by French poets Mallarmé, Baudelaire, and Rimbaud, novelist James Joyce, and other writers.

— Christina Petrowska Quilico, edited by Linda Litwack