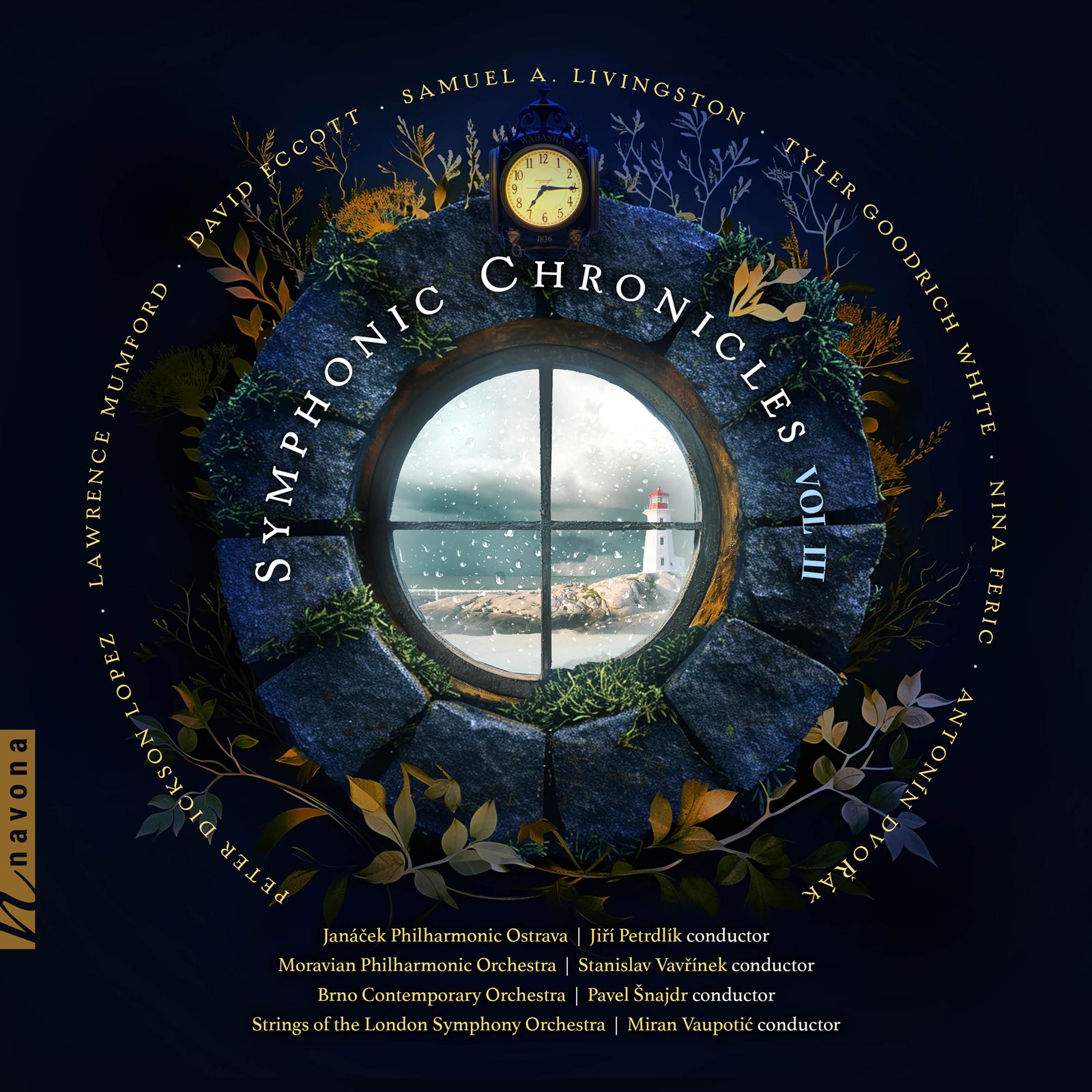

Embracing the same spirit of innovation and artistic exploration that captivated audiences in its previous installments, SYMPHONIC CHRONICLES VOL III unites a diverse assembly of today’s leading composers and performers. This edition offers listeners a variety of themes and moods to explore, from perspectives of an ancient civilization to Croatian folklore, remembrance of those we’ve lost, odes to the tranquility and vastness of our natural world, and more.

PARMA Senior Content Writer Shane Jozitis recently connected with the composers of DIMENSIONS VOL. 5 to learn about the inspirations, processes, and realizations behind their works. Read on for an exclusive deep dive into the creative minds of Tyler Goodrich White (TGW), Lawrence Mumford (LM), David Eccott (DE), Samuel A. Livingston (SL), Peter Dickson Lopez (PDL), and Nina Feric (NF).

SYMPHONIC CHRONICLES VOL III lends a fresh perspective and unique voice to the celebrated tradition of classical orchestral music. As a composer, how do you strike a balance between innovation and aligning with the traditions of classical music?

TGW: In conceiving new musical works and experiences, I delight in reimagining venerable norms of the classical tradition, using an eclectic harmonic language and sometimes willful distortion of familiar formal procedures. In the first movement of The Four Elements, for example, I began with a relatively conventional sonata-form exposition, but then dispensed with the development and recapitulation, cutting directly to a climactic coda. Rather than pursuing innovation for its own sake, I seek to bridge contemporary explorations with the practices of a still-living past. Overarching all this is my obsession with finding the “right” sound and technique for any given piece to create a musical experience at once fresh yet oddly familiar, prompting the listener to wonder, “Wow — why haven’t I heard this before?”

LM: Yes, I agree that the key word is “balance.” On the one hand, in an orchestral concert, it is most likely that a living composer’s piece will be performed before or after some well-known masterwork. A certain aural continuity is expected. Yet it is now 2024, not 1924 or 1824, and more recent musical techniques have found their way into the art of music and even into the subconscious of most listeners. So by drawing from, say, the musical language of film scores, or from the melodic and harmonic patterns of recent popular music, combined with the formal designs and dramatic pacing of the masters, it should be at least theoretically possible to create something that is both linked to the past and yet relevant to the present.

What’s a musical idea or technique that you’ve always wanted to explore but haven’t yet, and how would you explore the concept if given the chance?

LM: As I suggested previously, I think musical continuity is important. Yet today’s composer has access to a vast array of percussion instruments, many of which were not known to most of the famous masters. I would like to explore the potential of many of these in an extended piece for orchestra.

DE: For me, “wanting” to write something or “wanting” to explore an idea or technique is the wrong approach to any composition. I tend to follow the concept of “not writing the music, but allowing the music to write itself.” In other words, letting the creative process proceed naturally without overthinking anything or forcing anything to fit a preconceived model. Once the music, even if it’s only fragmentary, presents itself, the nature of the idiom and genre becomes obvious. Sometimes I have to wait a long time for that to happen, and then, if I get stuck midstream, I may have to wait again until something unfolds, but once it does I can, hopefully, develop the ideas in an intuitive and organic manner. If all goes well, the music seems to take on a life of its own.

Can you recall the emotions you felt when hearing this work performed for the first time?

SL: Before I heard a live performance of the piece on this album, I heard a remarkably lifelike synthesized version created by the publisher’s software. When I heard it, I thought, “Wow! That’s just the way I wanted it to sound. And it’s really good!” The first live performance I heard (so far, the only one I’ve heard) was the recording session. I was listening through headphones at my computer at 3 am (which was 9 am where the piece was being recorded). I was concentrating on making sure the tempo was appropriate and that the balance was OK. At that time, my reaction was “Yes, they got it right.”

What is the most unusual or unexpected source of inspiration you’ve ever had for a composition?

PDL: Some years ago while cleaning house and coincidentally browsing through historical family records, I came upon an elementary school project of my son, Peren, which was a collection of his own poems and drawings describing and illustrating various moons, such as the Harvest Moon, of which there were 13. Although tempted to use these poems and drawings as the basis for a work, I quickly knew that I was not interested in a “Pictures at an Exhibition” kind of work. I decided instead to write a work reflecting my own memories and feelings during the childhood years of my son as shared with my beloved wife, Irene. Considerable time passed before I began to work on this project about two years before Irene passed away in 2022, and indeed continue to work on afterwards. This was a very difficult, emotional, and trying time for us, and so on another level, this work, which I titled Song of Thirteen Moons, is also an homage to my beloved Irene. Thus, Song of Thirteen Moons is not about moons per se, but rather embodies a metaphorical reflection of my inner life during this time.

NF: I really find inspiration everywhere and anywhere. People inspire me, as does traveling to different places, certain moments in time, my own experiences, stories other people tell me, or something I read in a book. Nature for me is a great source of inspiration, the sound of waves, wind rustling the leaves on the trees, soothing sound of a waterfall, forest sounds, or birdsong. I am also inspired by myths and legends, always creating in my mind my own images and representations of events, heroes and villains, mythical beings, and their emotions. Once I wrote an entire composition inspired by a bird signing on my window. And maybe the most unexpected one would be a piece on an elderly woman I saw once on a bus, and imagined her whole life, what she was feeling, remembering, and hoping for. But, I don’t really think that any source of inspiration is unusual or strange; everything that surrounds us, living or still, or even transcendental, relating to a spiritual realm, has its own voice and sound. We just need to listen carefully to hear it, and if we can, put it in music. Or words, or a picture. That’s what art is all about anyway.

Tyler Goodrich White is Professor of Conducting and Composition at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where he has served as Director of Orchestras since 1994. Under White’s direction, the UNL Symphony has been recognized as one of America’s outstanding collegiate orchestras. As a composer, White has received commissions from the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, the Cleveland Chamber Symphony, the National Symphony Orchestra, Lincoln’s Symphony Orchestra, and numerous other organizations. He was awarded a Silver Medal in the 2019–2020 Global Music Awards, and in 2020 he was awarded The American Prize for Orchestral Composition. White currently serves as Composer-in-Residence of Lincoln’s Symphony Orchestra.

Nina Feric, born in Zagreb, Croatia, began her musical studies at the age of 6. She obtained her Master of Music Degree in Piano Performance and Piano Pedagogy from the Music Academy of the University of Zagreb (Croatia) in the class of Prof. Veljko Glodic, and continued her studies at Postgraduate Course in Music Disciplines at DAMS Bologna (Italy).

David Eccott lives and works as a peripatetic instrumental music teacher, specializing in piano and brass in his home county of Kent in England. He studied trombone with Denis Wick, former principal trombone with the London Symphony Orchestra, and piano with Robert Collett at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London. He has worked as an orchestral freelance trombonist and was an examiner for The Associated Board of The Royal Schools of Music for 23 years. He also composes. His Concertino For Oboe And Small Orchestra and his symphonic poem Rochester Creek: Scenes From PreColumbian Utah for large orchestra have recently won online composition competitions.

As an internationally performed composer, Peter Dickson Lopez traces his musical roots to a broad range of influences from his tenure as a graduate student at the University of California at Berkeley, as a Tanglewood (USA) Fellowship Composer, and as recipient of the George Ladd Prix de Paris (1976-78). The eclectic nature of Lopez’s mature style stems no doubt from having worked directly with composers of diverse approaches and philosophies during his early years at Berkeley and Tanglewood: with Joaquin Nin Culmell, Andrew Imbrie, Edwin Dugger, Olly Wilson, Earle Brown at UC Berkeley (1972-1978); and with Ralph Shapey and Theodore Antoniou during his Fellowship at Tanglewood (1979). Even more influential to Lopez’s artistic development was his residence in Paris where he had the opportunity to listen to many live concerts of contemporary European composers as well as to attend numerous events at IRCAM.

Lawrence Mumford's music, published by eight different companies, has premiered in cities across the country. Movements from his Symphony No. 4 have recently become a part of the broadcast libraries of the largest classical radio stations in Boston, Washington DC, Cleveland, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and other cities, and have been played repeatedly — even being included in two stations’ “Ultimate Playlist.” This music is also available on major streaming services including Spotify, Amazon Music, and Apple Music.

Samuel A. Livingston was born in 1942, and served from 1966-1967 with the U.S. 4th Armored Division Band. Livingston currently resides in New Jersey and plays the clarinet in a community band, traditional jazz groups, and chamber music groups. As a composer, he is entirely self-taught. His recent (21st century) compositions include works for concert band and several chamber pieces, mostly for wind instruments.